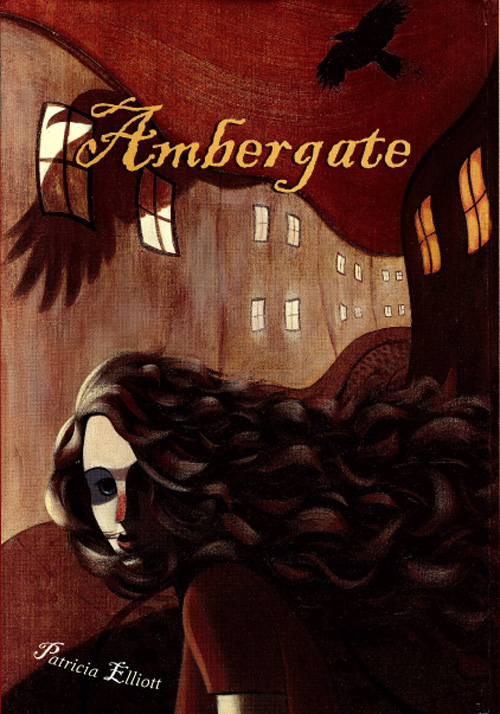

Ambergate

Authors: Patricia Elliott

Murkmere

Copyright © 2005 by Patricia Elliott

All rights reserved.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: November 2009

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Hodder Children’s Books

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental

and not intended by the author.

The superstitions in this novel are found in British folklore.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08863-3

Contents

F

or my husband, David—who is definitely

“the meaning of his name

”

The Eastern Edge

FIVE YEARS EARLIER

T

he little girl was hiding in the long grasses that fringed the mere.

She had never seen so much water before. She had never seen the way it changed as the sky overhead changed. And in this place

the sky was huge and filled with birds. She was frightened of birds, though she had been taught that some were more dangerous

than others. In the pocket of her pinafore was the rosemary she had picked from the kitchen garden to keep her safe.

No one would miss her in the house yet. None of the servants ever came down to the mere. They were fearful of the mud and

the deep, weedy water. In the nearest reed bed there was an empty nest, like a huge, upturned pudding bowl, from which grass

stuck out untidily. She was bored now, and beginning to whimper to herself at the thought of braving the kitchens again, when

she heard a voice close by.

“Come along, do! I’m taking you home. Can’t you walk faster?”

It was a child’s voice, impatient, bossy, and very clear, coming from over her head. She was too startled to be frightened,

and the little girl who had spoken, who looked a few years older than she was and clutched a boy smaller than them both, stared

down at her, equally surprised.

“What are you doing here?” the older girl demanded, and at her tightened grip on his hand the tiny boy began to wail. He was

wearing only a pair of breeches and a tattered shirt, and his chubby forearms were mottled from the cold. She was wearing

a velvet coat, laced boots, and a bonnet, and her face was pink with heat and the effort of tugging him along.

“Beg pardon,” whispered the little girl in the grass, knowing that she had somehow done wrong by being there.

“The mere belongs to me. No one else must come here.” She glared down. “My name is Leah. What’s your name?”

The little girl pulled back her left sleeve and held out her arm timidly. “Number 102.”

Frowning, the girl called Leah studied the branded numbers, the scars still red and puckered. There was a long pause.

“A number isn’t a name,” she said finally, dismissively. She nodded down at the little boy. “You’d better help me. Hold his

other hand.”

It sounded like a threat. The little boy’s hand was clammy and soft. As the girl took it, he looked up into her face with

a dark, trusting gaze, and his wails quieted.

“Where are we taking him?”

“Home, of course,” said Leah.

The three of them began to walk across the hard, sunlit mud. The boy toddled quite willingly now between the two of them.

At the water’s edge the younger girl halted, the little boy clinging to her hand. She looked over his head at Leah, puzzled

but not frightened yet.

“We can’t go no further.” She saw the older girl’s face and her voice grew uncertain. “Can we?”

Leah didn’t answer. She was looking over at the big untidy nest in the reed bed.

“Is that where he lives?” said the little girl. Anything was possible in this strange country place. But it didn’t seem right

that a tiny, tender boy should live there. She saw the gleam of the water and a little shiver of fear came to her in the sunlight.

“I’ll take him. You stay here.” Leah was bending down and unlacing her boots, beginning to unroll her white stockings. “Don’t

look, it’s rude.”

Obediently, she looked away.

Then suddenly there was a sound in the undergrowth behind them: a crashing and scrabbling like a large, bemused animal trying

to find its way, then a plaintive female cry. “Miss Leah! Miss Leah!”

Swiftly, Leah pulled on her stockings again and relaced her boots. The intent look in her eyes had vanished and her mouth

turned down mutinously “That’s my nurse. She mustn’t know I’m here.”

She lifted her skirts and ran away, past clumps of rushes toward the overgrown scrub. The other girl went on holding the little

boy’s hand, their two palms sticking together. She

didn’t know what to do with him. In front of her the water glinted and sparked in the sun; the baked black mud was under their

feet, and over their heads curved the vastness of the sky. It was all too big.

So she led him away from the mere.

The little boy knew his way home, then; he took her to a cottage. It was without a window and filled with smoke. The girl

saw a moving mound of clothes by the fire, bright eyes looking at them. She was too frightened to move, although she’d left

the door open. But the little boy ran straight across the earth floor, into the old woman’s arms.

She kissed and cuddled him, and all the time she was racked by bouts of coughing. When he had wriggled his way into her lap

contentedly and her crooning was done, she gazed at the little girl, smiling. Her face had been pitted by the pox, but her

eyes were beautiful and still young. The little girl couldn’t smile back; she wasn’t used to smiling.

She looked away. In the middle of the earth floor was a table, and spread out over it a cloak that shone in the half-light.

When she looked closer she saw it wasn’t made from cloth, but from long, silver-white feathers, the softness of the feathers

lying over the delicate, bony tracery of the barbs. She stared and touched her pocketful of rosemary, frightened yet curious.

The old woman was watching her, the child still in her arms. “You like the swanskin?” she said hoarsely.

The little girl shook her head, then nodded quickly.

The woman smiled again. “You will not forget it,” she said.

The boy scrambled off her lap and began to play with a long wooden box, opening and shutting the lid.

“Thank you for bringing my grandson back. What is your name?”

The girl shook her head and whispered, “I don’t have a name.”

“Everyone has a name,” said the old woman. “But some have to find it for themselves.” She coughed again, spitting into the

fire.

“You will find yours in the end, but only after a journey. It will take you far from here—far from Murkmere…”

I am the girl with no name. I have a number branded on my left arm, but no name

.

They call me Scuff, here at Murkmere. Soon after I was brought here from the Orphans’ Home in the Capital, they fixed on it,

on account of my big shoes, which made me scuffle when I walked. I have almost forgot what the old woman said to me about

a journey, for I never want to leave this place. And so I must be content with the nickname Scuff.

I have a secret. A secret I must never tell.

Once, when I lived in the Capital, I committed a crime. I did something so wicked I must never speak of it. If I did, they

would come after me: the Lord Protector and his men.

I think I did this wicked thing because of the ravens. I

remember them, those great black birds, their jarring cries as they shifted the air above my head. I think they made me do

it, those Birds of Night. Ravens. In the

Table of Significance

it says they are the birds of Death

.

One spring day, Jethro, the steward, had to leave us alone at Murkmere to go to a funeral. By then I’d been at Murkmere five

years or more, but that day my life changed.

After Jethro had ridden away, Aggie and I couldn’t shut the gates. During the winter they had become stuck fast in the ridged

earth.

Aggie took her hand away from the rusty iron. She looked pale in the morning light, as if she hadn’t slept.

“Leave them, Scuff. They won’t budge.”

Overhead a herring gull laughed mockingly, but the rooks were silent in the beeches, where they had new nest homes. I fingered

the amulet of red thread around my neck. “Jethro would want them shut while he’s away,” I said doubtfully. “Shall we dig them

free? I could fetch spades…”

Aggie shook her head almost angrily. “Who’s to come bothering us at Murkmere? We’re forgotten here.”

I always did everything Aggie asked, because she had been kind to me from the moment we met. So I stopped pushing against

the unyielding iron and turned to go back to the house. I’d mixed up sand and lemon the night before and had a day of pot-scouring

before me. Scouring is tedious work, but I like to see pots and pans winking from their hooks.

Aggie didn’t follow me, so I stopped. She was standing in the gap between the gates, staring wistfully out at the Wasteland

road. I thought she followed Jethro in her mind, was missing him already: Jethro, our young steward, who was Aggie’s love.

“Don’t you ever want to leave Murkmere, Scuff?” she said, surprising me.

I looked out at the long road stretching away into the distance. All you could see was sky and marsh and standing water. The

Wasteland was a wild place, and what might lie beyond it? Even standing between the gates of Murkmere, you could feel the

thrum of wind in your ears, the thrum of dangerous space.

I shook my head vehemently. “This is my home. Why should I ever want to leave?” Long-ago memories of the Capital stirred,

but I pushed them away.

Aggie sighed. “Sometimes I long…” She didn’t finish, but said, “Do you feel young still, Scuff, truly young still?”

“I’ve never felt young.”

“I did feel young once,” Aggie said. “But I don’t anymore, not nowadays. I feel old, as old as Aunt Jennet.”

“Jethro will be back in three days to help you.”

I didn’t know what else to say. We all worked too hard, and Aggie hardest of all. There were too few of us at Murkmere. Not

enough villagers had joined us over the last three years, since the old Master had died. They were fearful of leaving their

cottages open to vagabonds, fearful that the Lord Protector might suddenly decide to take the estate over and they would find

themselves in his employ. Jethro said the

Protector could not do such a thing lawfully, but I reckoned that, being the most powerful man in the country, he could surely

do what he wanted.

“I wish I could have ridden with Jethro. I long to see somewhere else—another place than this,” Aggie said, all at once passionate.

“But he said we shouldn’t go together in case anything happened to us. The Master made me official caretaker of the estate

before he died, and so it’s my duty to stay. But I envy Jethro. I do, Scuff!”

“Even with such a sad end to his journey?” I’d lowered my voice, although there was no need. There was no one to hear that

the steward of Murkmere was away to attend a certain funeral. But we had our story ready for anyone who should enquire: that

Jethro had gone to market early. Aggie bit her lip. “You’re right. How can I feel envy at such a time? Jethro is devastated

by the death of Robert Fane. In truth, Scuff, I don’t know what will happen to the cause now.”

It always made me nervous when Aggie talked of the rebels. Secretly I hoped that now their leader had been killed they would

cease struggling against the Protectorate, and on the Eastern Edge at least we could all lie easier in our beds.

We began to walk back to the Hall together in silence. Weeds had grown in the spring warmth and tough young grass sprouted

from the potholes of the drive. We had to walk on the verges, past the sheep grazing on the rough parkland. Aggie shook her

head at the weeds, and at the growth of creeper covering the front of the house.

“Everything’s even more overgrown than it was when the

Master was alive,” she said, twisting her hands together. “It’s so hard to keep this place going.”

“You do very well,” I said. I didn’t like to see her low-spirited, she who was so warm and generous and kind. “We wouldn’t

want the old days back again, any of us.” She smiled at that and tucked her arm into mine, and I was happy.

“See, Scuff. You’re nearly as tall as I am now and filling out a bit, I declare! You’ll never be as fat as I am, though.”

She was not fat, but big-boned. “How old are you, do you think?”

“They reckoned I was ten when Mr. Silas bought me at the Home, so may be I’m fifteen now, or thereabouts.”