Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer (25 page)

Read Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer Online

Authors: Maureen Ogle

Outside the hearing room, war alone had become sufficient reason to shut the brewers’ doors. On September 6, President Wilson announced that in order to preserve precious supplies of grain and fuel, breweries would close at midnight, December first. A few days later, the Food Administration cut brewers off from corn, rice, or barley. They could use their stock on hand; they could purchase any malt they could find. But when those supplies were depleted, well . . . that was that.

New York beermakers huddled in emergency session to discuss the bomb. “Nobody at the meeting had any suggestion to make as to what can be done with our properties,” Jacob Ruppert said afterward. “I haven’t the remotest idea as to what we can do with ours.”

Ruppert could always fall back on the income from his stud farm or from his New York Yankees, which he had purchased three years earlier. August Busch was less blasé. He had already converted his Busch-Sulzer Diesel Engine Company into a submarine engine manufactory for the navy. Now he offered the brewery to the United States government for use as a munitions factory and set off for Washington to seal the deal. “Give me a chance,” he promised, “and I’ll make the cartridge manufacturers look like pikers.” As for prohibition? asked a reporter. “I am not now interested in the prohibition question,” Busch replied. “I am only concerned now in doing what I can to help the Government, and, secondly, to take care of my employes [sic] in St. Louis.”

His New York colleagues scoffed at the idea. It was unlikely, said one of them, that the federal government wanted or needed yet another munitions factory. And, he added, “our men, brewers and malsters [sic] and the like, who have done nothing but the work they are engaged in all their lives, would make a poor fist at learning the munition-making trade or any other. None of them is young and it is difficult to teach old dogs new tricks.” His attitude may explain why August Busch survived Prohibition and many of the New York brewers did not.

Busch forged ahead, determined to save his family’s investment and his reputation. He ran a full-page advertisement in St. Louis newspapers announcing that he would hand over the entire seventy-five city blocks and $60 million worth of Anheuser-Busch facilities to federal officials if they wanted it, announcing, “We consider it a privilege to co-operate with the Government in making its war program effective.”

Busch devoted most of the ad to refuting the “false reports and statements” being “circulated with reckless disregard for truth.” Anheuser-Busch was “an American institution, founded by Americans more than 60 years ago, and continuously owned and operated by Americans” since then. (That, by the way, is true: Eberhard Anheuser became a citizen in 1848; Adolphus Busch in 1867.) He reminded readers that the company paid more than $3 million in taxes every year and employed nearly seven thousand men and women. The Busch family had contributed a half million dollars to the Red Cross and purchased $3 million worth of Liberty bonds. It was true that he and his mother had bought German bonds, but they’d done so eighteen months before the United States entered the war. “Anheuser-Busch was founded upon the solid rock of Americanism,” Busch concluded, “and grew to be a great institution under the protection of American democracy.” Now the company stood

“ready to sacrifice everything except loyalty to country, and its own honor, to serve the Government in bringing this war to a victorious conclusion.”

Government officials decided against converting the brewery to munitions production, but leased a large chunk of one Anheuser-Busch building for the storage of weapons and ammunition. The lease proved to be short-term: The war ended on November 11. On December 1, the nation’s breweries turned out their lights, as per President Wilson’s order of the previous September.

None of it mattered. While Wayne Wheeler and A. Mitchell Palmer hatched their plots; while August Busch struggled to save his name and his livelihood; while the Senate subcommittee muddled through an embarrassing waste of taxpayer money; while a generation’s finest—American and German, English and French—fought and died in the trenches of Europe, one state legislature after another had ratified the prohibition amendment. On January 16, 1919, Nebraska legislators voted aye. Theirs was the necessary thirty-sixth nod of approval. Prohibition had become the law of the land.

Best Brewing Company in its early days. This undated photograph likely was taken in the mid-1860s, not long after Phillip Best expanded the brewery and about the time that Pabst and Schandein joined the firm.

Photo courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society

Frederick Pabst and his wife, Maria, c. 1865, not long after he joined Best Brewing. A rare early image of the young man who twenty-five years later would own the largest brewery in the world.

Photo courtesy of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion Archives

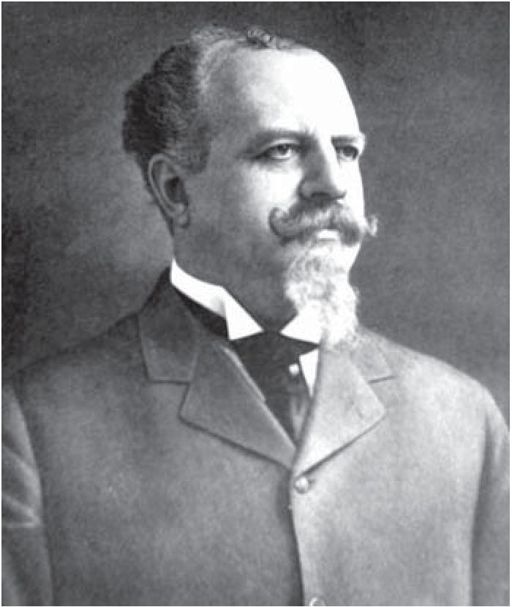

Adolphus Busch, c. 1890, when he ruled over one of the two largest breweries in the world. “I am an eternal optimist,” he once said.

Photo from

Western Brewer

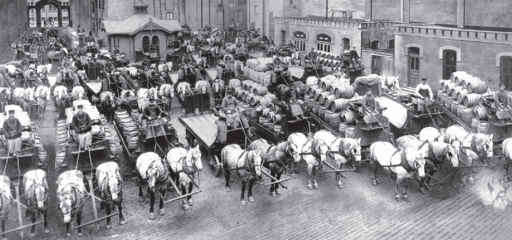

Best Brewing teamsters, c. 1875. The drivers are hauling their cargo to the rail yard for shipping to distant markets, but nineteenth-century brewers also paraded their drivers and wagons through the streets as a way of advertising their firms’ size and brewing prowess.

Photo courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society

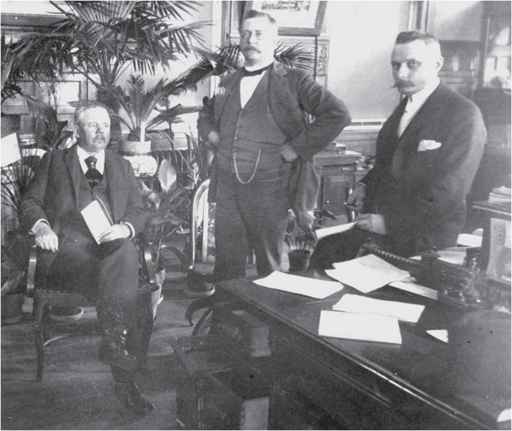

The Uihlein brothers, c. 1900. From left: August, William, and Alfred.

Photo courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society

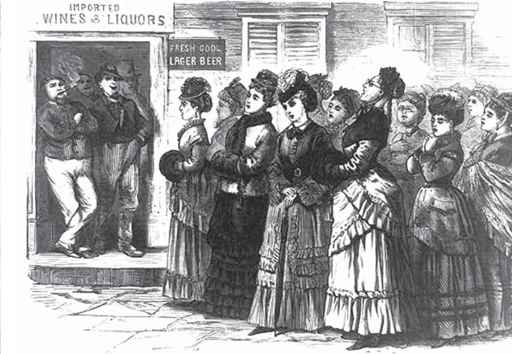

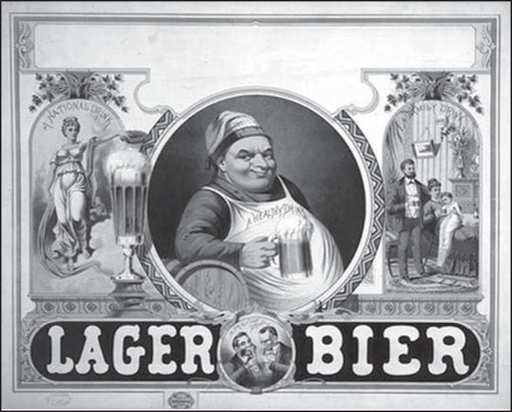

This poster from an unknown brewer emphasizes beer as a “healthy” drink respectable enough to be drunk at home. As the forces of temperance gathered strength after the Civil War, beermakers touted lager as the national drink and the beverage of moderation.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

(LC-USZC4-4439)

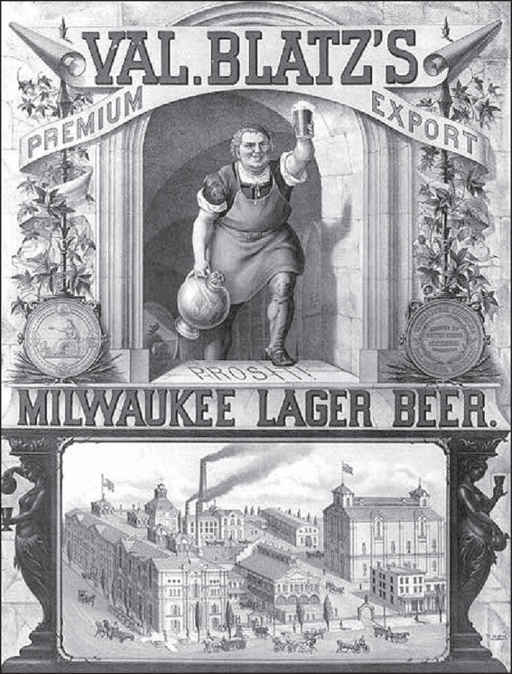

Brewers provided their “tied” houses with plenty of advertising material. Posters like this one often alluded to both the brewers’ old-world heritage and their American success—notice the image of Blatz’s imposing factory complex.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

(LC-USZ62-17080)

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 marked the last great face-to-face confrontation between Frederick Pabst and Adolphus Busch. Both men’s exhibits featured detailed models of their breweries. Even in miniature, this replica of Anheuser-Busch is imposing.

Photo from

Western Brewer,

courtesy of the Anheuser-Busch Corporation