American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (28 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

An M14 Enhanced Battle Rifle in the hands of a U.S. Army soldier in Kunar province, Afghanistan, January 2013.

U.S. Army (photo by Sgt. John Heinrich)

Now, it’s not just the rifle that matters. The guy at the trigger is important too. You don’t just wake up one day and shoot a tight group at eight hundred yards. A man may have God-given talents, but without practice he won’t be very good. That’s something that all good shooters, whether they’re snipers, Marines, or match competitors, have in common; they practice a lot, and they keep on practicing.

Then again, that philosophy applies to just about everything you do in life.

The M1 Garand is truly an American classic. But its day was shorter than just about every weapon we’ve hit on. The Garand showed the way of the future: more bullets, easy loading, rapid firing. Accuracy was important, durability more so. Past a certain point, range might or might not be a critical factor, depending on how the gun was being used.

Modern combat rifles had to be versatile and not too heavy. Cheap to produce was probably too much to ask, but that didn’t stop the bean counters from trying.

All of that pointed in the direction of the modern battle rifle, a weapon that could be used in a variety of situations. If it wasn’t exactly cheap, at least an army could use it for a bunch of jobs without having to purchase something else.

But before we talk about the gun that came to fill that wide niche, let’s take a step back to something closer to home—a classic American wheelgun, the .38 Special.

THE .38 SPECIAL POLICE REVOLVER

“Well, we’re not going to let you just walk out of here.”

“Who is we, sucker?”

“Smith, Wesson—and me.”

—Clint Eastwood as Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan,

San Francisco Police Department, in

Sudden Impact

President Harry S. Truman was in his underwear, fast asleep. Fifty yards away, two men in pinstripe suits approached, carrying hidden semi-automatic 9mm pistols, one a Walther P38, and the other a Mauser-produced Luger. They were going to kill the president.

They planned to storm the steps of the temporary presidential residence at Blair House, across the street from the White House, then undergoing renovations. They would shoot the guards, hunt down Truman, and execute him.

It was 2:20 p.m. on November 1, 1950. Truman was catching some rest as he often did in the afternoon, napping in a front bedroom on the second floor of Blair House. His room was just a short dash up two flights of stairs from the street and sidewalk. If the president had been looking out the room’s window, he would have seen the two approaching assassins: Puerto Rican revolutionaries Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola as they walked from opposite directions toward the house.

Defending the building was a small force of White House Police and Secret Service officers, all carrying .38 caliber revolvers. The Secret Service had two-inch-barrel Colt Detective Specials, and the White House Police, who were under the command of the Secret Service, had four-inch Colt Official Police models on their hips. Both Colts were very good handguns, members of the .38 Special family used by police everywhere in the country. The wheel guns were reliable, nearly cop-proof, and best of all, inexpensive.

The Blair House property was actually two buildings; the Lee House sat on the Blair’s west, attached inside though from outside they looked separate. They were close to the sidewalk and the street, both of which were open to the public. A tiny guard house stood on the sidewalk at each end of the property. A decorative wrought-iron fence flanked the sidewalk. Canopies covered the stairs in front of both houses.

Seeing his accomplice approaching the western guard house, Oscar Collazo walked past the post on the east side and took out his Walther P38. Walking toward the steps, he pointed it at uniformed White House police officer Donald Birdzell who was standing on the sidewalk near the street, his back to him.

Collazo pulled the trigger.

The pistol didn’t fire. Collazo didn’t know the gun well, and in his rush he’d gotten all confused. Most likely he had accidentally flicked on the safety; the hammer snapped down without doing anything but making a loud click.

The assassin struggled with the gun. The officer turned to face him. Finally the German-made Walther fired, and Officer Birdzell fell, bullet in his knee. Stumbling as he tried to get up, Birdzell pulled his gun and tried to answer Collazo’s shots with his own. Another White House Police officer and a Secret Service officer drew their guns and opened fire, but their bullets were wild or deflected by the bars of a wrought-iron fence between the assassin and themselves. Then a bullet ripped through Collazo’s hat, grazing his scalp. He didn’t seem to notice it, pulling the trigger to return fire.

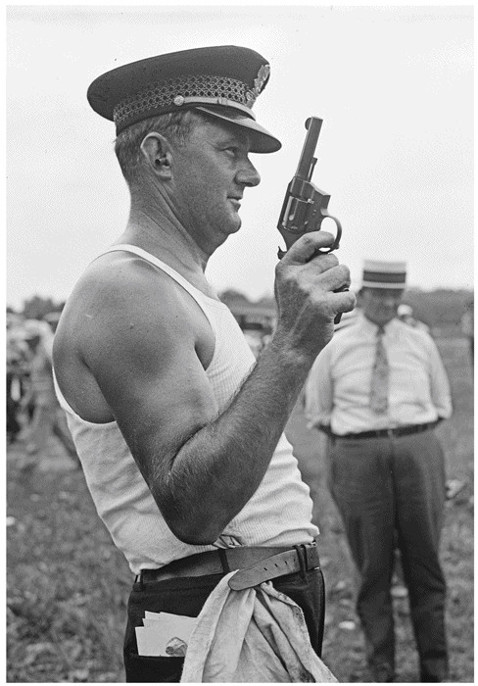

“Crack shot of White House police force.” A colleague of the officers who defended President Truman on November 1, 1950, displays the pistol he used to hit 294 out of 300 bull’s-eyes during a competition. .38s remain popular marksmanship weapons.

Library of Congress

Meanwhile, Griselio Torresola stepped in the guard house on the west side and fired three times point-blank into White House policeman Leslie Coffelt’s chest and stomach. Torresola then spun from the guard house and walked on toward the steps to help Collazo. Along the way he shot a plainclothes White House policeman in the hip, chest, and neck.

Inside Blair House, a Secret Service agent heard the gunfire and ran to fetch the Tommy gun from the gun cabinet. It was locked, and he fumbled with the key.

In the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue, Birdzell regrouped. He saw Torresola coming at him, and tried to line up a shot. Torresola was quicker. He fired a bullet into the policeman’s other knee. Birdzell collapsed, out of the fight. Torresola calmly reloaded his Luger and kept moving toward the steps.

His accomplice, Collazo, suddenly realized he was out of bullets. He sat down and started to reload.

It’s never good to have to reload when people are shooting at you, but it’s especially bad when you have no cover and are extremely close to your enemy. The president’s guards kept firing. One of their bullets finally made him stand up, wobble, then slam face-first to the pavement.

Harry Truman, startled awake by the gunshots, went to his second-story bedroom window. The president raised the window and looked down at the scene, trying to figure out what was going on.

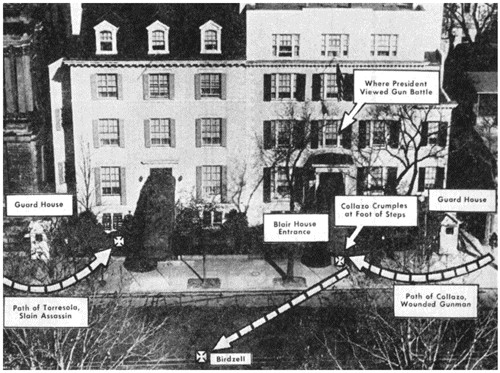

A diagram of the attempted assassination of President Truman.

GhostsofDC.org

Torresola was slapping a fresh magazine into his pistol some thirty feet away. It was an easy pistol shot. But before Torresola spotted him, Leslie Coffelt staggered out of his guardhouse. The severely wounded officer raised his .38 and fired.

The forty-year-old officer’s aim was true. A 158-grain lead bullet spun into the skull of Griselio Torresola. His body shook as if it were possessed by the devil as he fell.

It was the last of about thirty shots fired during the forty-second gunfight. Someone saw the President at the window, and yelled at him to move away. But it was all over.

Leslie Coffelt died of his wounds. He is the only officer serving under the command of the U.S. Secret Service to ever have died while protecting a president. Oscar Collazo survived and was sentenced to death for the murder of Coffelt. Harry Truman commuted his sentence to life so he’d stew in jail for the rest of his days, instead of becoming a martyr to Puerto Rican nationalists. For reasons I haven’t been able to understand, Jimmy Carter pardoned him in 1979, and Collazo returned to Puerto Rico to a hero’s welcome.

Truman was said to have been deeply shaken by the close call, and haunted by the memory of Leslie Coffelt sacrificing his life for him. It’s been argued that the bloody events contributed to his decision not to run for reelection to a full second term.

Given what the Secret Service goes through today to protect the President, the security around the Blair House that day in 1950 looks ridiculously thin. If Collazo knew his weapon better or packed two pistols instead of one, odds are he would have been inside Truman’s bedroom before the President pulled on his trousers. But consider this—America was the kind of place in 1950 where the president could walk around Washington, D.C., with only a single Secret Service agent tagging along. Usually he went with four, but Truman took a walk just about every day and didn’t like waiting; the rest of the detail had to catch up or catch hell. The buck stopped on Truman’s desk, but he didn’t stop for anything, and didn’t think much about his personal security.

That was all going to change. America was becoming a different place. And the police were the ones who’d be caught in the middle.

The first full-fledged municipal police force in America was started in New York City in 1844. The police started carrying pistols in the late 1850s. For the next forty years or so, they armed themselves with a hodgepodge of guns. The officers got about as much training as a SEAL gets dance lessons. When he came on as police commissioner, Teddy Roosevelt made the .32-caliber Colt New Police revolver the regulation police handgun. He also set up a marksmanship program, led by national shooting champion Sergeant William Petty.

Other big cities moved in the same direction. They were all dealing with similar problems: booming population, crowded living conditions, corruption, vice, immigration, criminal gangs—the entire dark side of an increasingly urban nation.

Once police departments decided to arm their officers, they faced difficulties armies don’t have. Like the military, they needed weapons that were dependable and could stop a bad guy cold. But whatever they picked had to be suited to everyone on the force, big or small. That might not seem like much when a police force has mostly oversized Irishmen who like to crack heads, but step away from the cliché to modern forces with officers of every size, shape, and gender, and you see the dimensions of the problem.

In “traditional” warfare, armies didn’t waste much thought worrying about civilians getting hurt. Police departments, on the other hand, spend all their time around civilians. They have to suit their weapons to the threat they face, but not go overboard. A bullet that stops a criminal and then goes into the next building can turn a clean collar into a tragedy.

Even in the worst crime pits, most police officers never have to fire on a suspect. Many officers usually only fire a handful of times in their career, if that. So they need guns handy, but still tucked away. Last and not least, whatever they get has to be inexpensive. Not cheap, but a good value. A buddy of mine from San Diego, Mark Hanten, is the commanding officer of the SDPD SWAT team. Mark pointed out recently that his department has some eighteen-hundred-plus cops, and some, like the LAPD, well over eight thousand. Buying a weapon for all of them can put quite a dent in the taxpayers’ pockets.