American Tempest (24 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

New York's Lieutenant Governor Colden was leading that colony in the same direction. “All men of property are so sensible of their danger from riots and tumults,” he boasted, “that they will not rashly be induced to enter into combinations which may promote disorder for the future.”

7

Thomas Cushing, the quiet, thoughtful merchant who was Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, agreed, urging moderates to prevent “a rupture fatal to both countries.”

8

And John Adams confessed in his diary, “I shall certainly become more retired and cautious. I shall certainly mind my own farm and my own office.”

9

Like many merchants in Boston, farmers outside Boston and across New England turned against Boston's radicals for misrepresenting the events leading up to the massacre, and in England the testimony from the Preston trial turned public opinion squarely against the people of Boston. As Parliament debated appropriate punishment for Boston's duplicity, even the staunchest colonist defenders spoke of Boston as a lawless city of ruffians and a hotbed of anarchy.

As distaste increased for the rowdyism of Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty, Governor Hutchinson sensed an opportunity to reconcile with John Hancock. The entire merchant community was abandoning Adams and the street toughs, who had sullied Boston's reputation, hurt trade, and given Philadelphia and New York opportunities to surpass Boston as primary trade centers in America. Hancock's own tolerance for street mobs had also worn thinâalong with his inclination to cover the personal and public debts of the profligate Sam Adams.

In the spring, a Loyalist resoundingly defeated Sam Adamsâby a two-to-one marginâin the election for Suffolk County Registrar of Deeds. After Hancock easily won reelection to the General Court, Hutchinson confided, “I was much pressed by many persons well affected in general to consent to the election of Mr. Hancock. They assured me he wished to be separated from Mr. Adams. . . . I have now reason to believe that, before another election, he will alter his conduct so as to justify my acceptance of him.”

10

Although the House of Representatives had consistently elected Hancock to serve on the Governor's Council, Hutchinson had exercised his veto just as consistently. In June 1771, however, he assured Hancock he did not bear “any degree of ill-will towards him” and that “it would be a pleasure to consent to his election to the Council.” Hancock surprised the governor by refusing the offer, saying he intended to abandon public affairs to attend to his private business, which, he said, he had neglected for too long. And at the governor's festive official Christmas banquet, Hancock confided to the governor that he would “never again connect himself with the Adamses.”

11

As the new year began, Sam Adams's radical movement faced collapse. In a letter to former Governor Bernard in London, Hutchinson all but proclaimed victory: “Hancock has not been with their club for two

months past and seems to have a new set of acquaintances. . . . He will be a great loss to them, as they support themselves with his money.”

12

He omitted the news that a court had declared James Otis

non compus mentis

and appointed his younger brother as guardian.

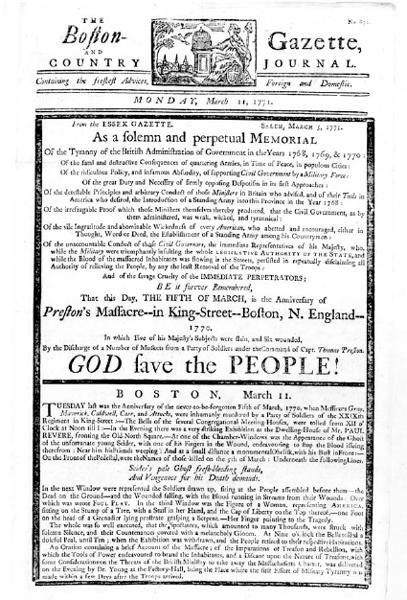

Hancock's relations with the governor warmed considerably, as did those of Thomas Cushing. Together, the two moderates approached Hutchinson about moving the General Court back to Boston from Cambridge. They agreed to base their resolution solely on convenience rather than the constitutional grounds that Sam Adams had cited. Even radicals had wearied of Adams's all-but-mindless obstructionism in the General Court. In fact, one of his closest allies, Dr. Benjamin Church, switched to the Loyalists and wrote newspaper articles that all but ridiculed Adams. The proroyalist movement spread elsewhere, with conservatives winning elections in New York, Philadelphia, and even in Patrick Henry's Virginia. Samuel Adams raged in the

Boston Gazette

against “the silence of the other assemblies of late upon every subject that concerns the joint interest of the colonies.” He asked John Dickinson to write more “Letters” to rouse the people from “dozing upon the brink of ruin,” but Dickinson declined.

As spring elections approached, Hutchinson and the resurgent Loyalists hoped to oust Sam Adams from government and silence his voice. Knowing that he was too incompetent to support himself in normal trade, they believed his removal from political power would extinguish the last embers of rebellion. Although one-third of Boston's eligible voters cast their ballots against him, Adams nevertheless won reelection. Both Hancock and Cushing received nearly 40 percent more votes than Adams, and they teamed up to defeat his radicals in the House of Representatives by passing a modest request for the General Court to return to Boston. In June the governor replied, “It is his Excellency's pleasure that the great and General Court or Assembly be adjourned till Tuesday next at ten the clock in the forenoon, then to meet at the Court House in Boston.”

13

Sam Adams continued trying to disrupt the General Court, as Hancock and other moderates yawnedâand finally adjourned.

In the autumn King George ordered the royalist leadership to court Hancock's allegiance, and Governor Hutchinson bestowed one of the province's highest honors on the thirty-five-year-old merchant: “His Excellency

the Captain-General has been pleased to commission John Hancock, Esq., to be Captain [commander] of the Company of Cadets, with the rank of Colonel.” Sam Adams lashed out angrily, scoffing that “it is not in the power of the Governor to give a commission for that company. Their officers are chosen by themselves. Mr. Hancock was elected by a unanimous vote.”

14

In fact, Adams was correct. The governor had no authority to “commission” Hancock. Called the Independent Corps of Cadets, Hancock's new command was a fraternal, “gentlemen's militia” of eighty men who served as the governor's honor guard, marched at official ceremonies, and spent as much time as possible at the Bunch of Grapes tavern. Hancock had joined the guard, as he had the Freemasons and the Merchants Club, for informal fellowship with men of similar backgrounds and interests. As Adams stated, the corps did, indeed, elect Hancock, but his election was a recognition of Hancock's leadership among Boston's wealthiest, most responsible citizens, and the governor's meaningless commissioning was a gesture of reconciliation.

The election/appointment sent Hancock into spasms of ecstasyâa military command to complement his civic and political leadership. For someone who adored the trappings of leadershipâand recognized their importance in commanding awe and respectâcommand of the corps could not have been a more perfect acquisition for John Hancock. He envisioned himself in regimentals with sparkling gold epaulets, atop a white horse, sword at his side. He set to work immediately, passionately, converting his vision into reality. He ordered magnificent new uniforms for the entire corps: scarlet coats with buff lapels, white gaiters with black buttons, and three-cornered beaver hats with brims turned up smartlyâone of them bearing a rosette secured by a gilded button. He drew up a small manual of arms and asked his former adversary, the British commander Colonel Dalrymple, to assign a sergeant to drill the cadets in precision marching. A few days later, Boston newspapers carried this advertisement:

Wanted. ImmediatelyâFor his Excellency's Company of Cadets.

Two Fifers that understand playing. Those that are

masters of musick and are inclined to engage with the

Company are desired to apply to Col. John Hancock.

15

The Corps of Cadets began drilling twice a month in Faneuil Hall and moved onto the Common for compulsory weekly drills on Wednesdays when the weather turned warm in spring. Hancock fined those who missed drillsâusually a round of ale at the Bunch of Grapes. It was not long before Colonel Hancock and his Corps of Cadets looked every inch a precision marching team, and rumors circulated that the crown was preparing to confer a title on him. Hutchinson knew that John Hancock's adoration of pomp and life at the highest levels of British society as Lord Hancock would end his association with Sam Adams and the radicals.

Neither King George nor his minions, however, were as farsighted as Hutchinson (or democratic enough) to consider elevating American commoners to the nobility as a tool to command colonist loyalties. Hutchinson did the next best thing, however, by again inviting Hancock to join the Governor's Council, and again Hancock refused. Hutchinson wrote that Hancock's refusal was simply an effort “to prevent a total breach” from the radicals and “show the people that he had not been seeking after it.”

16

Hancock's refusal, however, probably had nothing to do with either. He had simply grown frustrated with politics and the inability of the General Court to produce practical benefits for Boston. Through the entire winter of 1771â72, the only accomplishment of Boston's selectmen was to name a Massacre Day orator to commemorate the March 2 confrontation. His boredom with selectman meetings reduced his attendance dramatically. He decided he could accomplish more on his ownâas his uncle had done in restoring and maintaining the Common. With Thomas Cushing, who preferred to keep his contributions all but anonymous, he financed the building of a bandstand on the Common and organized and paid a band to give free concerts. He planted a row of trees along the edge of the Common fronting Beacon Street and installed walkways that criss-crossed the park and allowed strollers to enjoy the green without destroying it. He contributed £7,500 to rebuild the crumbling Brattle Square Church. In March 1772 the town appointed him chairman of a committee “to consider the expediency of fixing lamps in this town,” and a year later, with Hancock and Cushing pledging to cover costs, they ordered three hundred white globes, which used whale oil for illumination and would be the most advanced type of street lamps in America. Having lost some of his

own properties to the perennial fires that raged through Boston's narrow streets and alleys, Hancock ordered the latest model fire engine from England as a gift for the town. To thank their benefactor, the town meeting named the engine “Hancock” and ordered it housed “at or near Hancock's Wharf and in case of fire, the estate of the donor shall have the preference of its service.”

More and more, Hancock relished the power he could exert with his wealth and the immediate, visible improvements he could effect in Bostonâwithout having to coax ignorant, timid, or imperious government officials and political opponents. With Cushing always offering support but preferring to remain in the background, Hancock's lavish contributions quickly made him Boston's most popular political leader, eclipsing Sam Adams. The radical majority at the town meeting voted him, rather than Sam Adams, moderator, or presiding officer. Adams was furious. He had invented Hancock and the radical movement, and both now ignored him.

Adams could do nothing, however, but await Parliament's first misstep to reignite mob passions with inflammatory propaganda and seize control of Boston politics again. Parliament did not disappoint him. It enacted a bill restoring the element of the Townshend Acts that made the crown, rather than colonial legislatures, responsible for paying the salaries of judges, thus making the courts dependent on the king instead of the colonial legislatures.

“The judges,” Chief Justice Peter Oliver recalled, “had agreed to accept it, but . . . four of them who lived at and near the focus of tarring and feathering . . . were so pelted . . . with cursings and threatenings” that they resigned. Oliver himself accepted the king's order that he be paid by the crownâonly to have Adams order his mob “to attack the chief justice when he came to court.”

17

Adams converted the new law into a cause célèbre, writing in the

Boston Gazette

, “Let every town assemble. Let associations and combinations be everywhere set up to consult and recover our just rights.” His article caused a furor. Overruling Hancock's and Cushing's objections, Adams organized a “Committee of Correspondence” at the town meeting “to state the rights of the colonists and of this province in particular, as men, as Christians, and as subjects: to communicate and publish the same to the several towns in this province and to the world.”

18

His committee would prove the first link in a chain of committees he encouraged the colonies to establish. The Intercolonial Committee of Correspondence that resulted was the first permanent system of communication between the American colonies and their first union of sorts. Adams demanded that the committee encourage other towns and colonial assemblies to establish similar groups to work in unison to overthrow royal rule. Recognizing that Adams would use the Committee of Correspondence as a springboard to revolution and power, Hancock, Cushing, and other moderates objected. Adams had enough votes, however, to form a twenty-one-man committee that Governor Hutchinson called the “foulest, subtlest, and most venomous serpent ever issued from the egg of sedition.”

19

Hancock, Cushing, and other moderates refused to serve on the Adams committee, with Hancock using the press of business as an excuse. Adams, however, did not intend to allow Hancock's money to slip from his grasp, and cunningly set about repairing the political machine he had earlier assembled so carefully.