American Tempest (34 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

The following morning, New York delegates joined those from Massachusetts and Connecticut at the North River Ferry to begin the trip to Philadelphia. Huge military and civilian groups hailed them on both sides of the river and at every city, town, and crossingâat Newark, Elizabethtown, Woodbridge, New Brunswick, Trenton, Princeton. . . . To ensure

the safety of the procession, each town's militia turned over escort duties to the succeeding town.

On the morning of May 10, the huge procession reached Philadelphia, led by an escort of two to three hundred mounted militiamen with swords drawn. Philadelphia was larger than Boston, with a population of about twenty-five thousand squeezed into an area twenty-five blocks long but only twelve blocks wide. Squalid slums covered the western part of the city, but the area around the State House boasted wide, tree-lined streets with brick walkways lit by whale-oil lamps. Again, church bells pealed and crowds roaredâsomewhat to the envy of delegates from other colonies who were waiting impatiently for the Second Continental Congress to convene. But even they agreed that Hancock, more than anyone else there, had made enormous sacrifices for the Patriot cause and deserved public acclaim. He had lost his sloop

Liberty

, spent at least £100,000 of his own money on arms and ammunition, and risked the rest of his fortune on the success of the revolution. If arrested on the king's warrant, he faced trial on charges of treason, with the possible loss of both his honor and his life. Even as Hancock arrived in Philadelphia, British General Henry Clinton, who had come to assist General Gage, had comfortably settled into Hancock House on Beacon Hill and was drinking his fill of fine Madeira wine from Hancock's prized cellar.

The raucous procession for Hancock and the New Englanders notwithstanding, the Second Continental Congress convened as scheduled on May 10 at the Pennsylvania State House. Hancock was one of several important new facesâanother being the venerable Benjamin Franklin. Although not a new face, forty-three-year-old George Washington drew admiring stares from all the delegates. He looked superb, conspicuously dressed in the commander's striking blue-and-buff uniform of the Independent Regiment of Fairfax, Virginiaâthe only delegate who had come dressed for war.

From the beginning, Congress had little opportunity for quiet reflection. Outside the State House windows, twenty-eight Philadelphia infantry companies drilled twice a day to the incessant squeal of fifes and the roll of drums. Inside, regional antagonisms delayed some of the most basic organizational proceedings. The southern provinces had longstanding disputes with New England colonies over territorial claims in the West. Moreover,

the South, which had no intention of arming its slave majority, had far smaller militias than the North, and some southern delegates feared that the huge Massachusetts militia might take advantage of a colonist victory over Britain to replace British rule in America with rule by New England.

Although delegates reelected Virginia's Peyton Randolph as president, North-South frictions surfaced when Randolph resigned abruptly and returned home after only two weeks. In the debate over a possible replacement, northern delegates grew as annoyed by Virginia's preponderant influence in Congress as southern delegates were by Massachusetts influence in military affairs. John Adams and George Washington, however, stepped forward with a solution.

They had developed one of the few truly collegial relationships that crossed the North-South barrier. Physically, they were an incongruous pair. Washington was the most visible delegate. At six feet, four inches, he towered over most of the others. Although forty-three, he was fit and strong. In contrast, the forty-year-old Adams was one of the least imposing delegates. As his wife conceded, he was “short, thick and fat.”

7

Although some delegates considered Washington aloof and unfriendly, Adams found “something charming . . . in [his] conduct,” and he admired Washington's willingness to risk his enormous fortune by supporting the rebellion.

8

As northerners accused southerners of slighting them in the presidential selection process, Adams and his new friend Washington acted to ease tensions and convinced Benjamin Harrison, another Virginia planter, to support them. Without Georgia, Congress was evenly divided between north and south, with the North consisting of New York, New Jersey, and the four New England colonies, whereas the South encompassed all the other coloniesâand Pennsylvania.

With the support of Washington, Harrison, and the other Virginians, John Adams nominated John Hancock for the presidencyânot just because of his personal sacrifices but, as Adams accurately stated, because of his years of experience as a moderatorâat Boston town meetings, in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and, most recently, at the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. In all three, he had often reconciled Loyalists, moderates, and radicalsâeven rural interests with urban interests. At the urging of Virginians, other southern delegates joined the rest of Congress

in electing John Hancock unanimously. Amidst “general acclamation,” the southerner Benjamin Harrison led the northerner Hancock to the chair and proclaimed, “We will show Great Britain how much we value her proscriptions.”

9

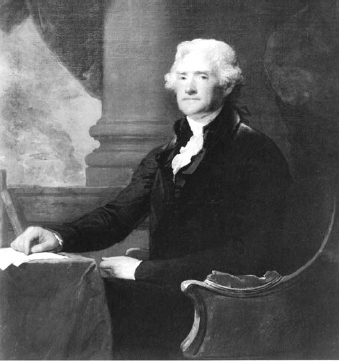

In addition to North-South divisions, Hancock faced a second, three-way political divide in Congress between radicals, moderates, and conservatives, whose membership had little to do with geography. Congressional radicals led by Sam Adams demanded nothing less than a declaration of independence from Britain. Philadelphia's John Dickinson, whose “Farmer's Letters” had brought him international renown, led the conservatives, with Boston's Thomas Cushing abandoning Sam Adams and supporting Dickinson. Dickinson, Cushing, and other conservatives sought nothing more than a redress of grievances and a return to the normalcy of preâStamp Act days. They found an effective voice to enunciate their amorphous goals in a new delegate who arrived late and took his seat just as Hancock took over the presidency of Congress: thirty-two-year-old Virginia legislator Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had written a widely circulated essay “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” which accepted the king's sovereignty in America but insisted that provincial legislatures held all legislative authority, including authority over taxation, and that “British parliament has no right to exercise authority over us.”

As moderator, Hancock had to remain impartialâand did. Although his neutral stance incurred the growing enmity of Sam Adams, he won the respect of all other delegates. No longer the fiery Tea Party Patriot of Massacre Day, he metamorphosed into the perfect president, with some appeal to all factions and favoritism for none. He understood everyone's point of view. His experience as moderator and legislator appealed to moderates; his wealth, business position, and education appealed to conservatives; and his defiance of British authority in Boston appealed to radicals. And what appealed to all was his vast experience directing a large organization, namely the House of Hancock.

His broad appeal cannot be overstated for a body made up not of

united states

, but of twelve separate and independent colonies with no ties to each other. Indeed, they had seldom communicated with each other until Adams and Henry established the network of committees of correspondence

a year earlier, and few had ever met face to face as a group until six months earlier at the First Continental Congress. Although all were powerful leaders in their individual states, all were equals in Congress, with each state delegation, no matter how large, able to cast but one vote.

For the first month Hancock tried to pick men from these disparate delegations to work together in committees and to keep the larger body intact, focused and moving forward in pursuit of a common agenda. Along the way, he had to prevent defections, soothe injured feelings, and calm any anger over perceived slights or oversights.

“Such a vast multitude of objects, civil, political, commercial and military, press and crowd upon us so fast that we know not what to do first,”

said John Adams about the opening days of the Continental Congress. “Our unwieldy body moves very slow. We shall do something in time.”

10

On June 2, Dr. Benjamin Church arrived from Boston with a letter from Dr. Joseph Warren, the new president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, urging the Continental Congress to assume control of the disorganized intercolonial army laying siege to Boston and appoint a commander in chief.

“The army now collecting from different colonies is for the general defense,” Warren wrote. “The sword should, in all free states, be subservient to the civil powers . . . we tremble at having an Army (although consisting of our own countrymen) established here without a civil power to provide for and control them. . . . We would beg leave to suggest to your consideration the propriety of your taking the regulation and general direction of it.”

11

In a separate, more dire letter to Samuel Adams, Warren warned, “The continent must strengthen and support with all its weight the civil authority here; otherwise our soldiery will lose the ideas of right and wrong, and will plunder, instead of protecting the inhabitants.”

12

A week later John Adams proposed, and the Continental Congress agreed, to make the Patriot forces besieging Boston a national “Continental Army,” and it appropriated £6,000 for supplies.

Two days later General Thomas Gage imposed tightened martial law over Boston and declared all Americans in arms and those siding with them to be rebels and traitors. To avoid unnecessary bloodshed, however, he issued a general amnesty in Massachusettsâto all but two men: John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

“In this exigency of complicated calamities,” Gage wrote in the am nesty, “I avail myself of the last effort . . . to spare the effusion of blood; to offer . . . in His Majesty's name . . . his most gracious pardon to all persons who shall forthwith lay down their arms and return to their duties of peaceable subjects; excepting only . . . Samuel Adams and John Hancock, whose offenses are of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment.”

13

Gage's amnesty made it official: Hancock and Adams were now fugitives from justice, wanted by the British government for treason and subject

to arrest on sightâwith all-but-certain death to follow. Gage offered a reward of £500 each for their capture.

Infuriated by Gage's assault on its president, Congress resolved to raise six companies of riflemen in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to march to New England, and Hancock appointed a five-man committee to draft rules for the administration of the army and name a commanding general. With each delegation eager to name a worthy patriot from his state, the committee decided to give the top position to the most qualified man they could find. Hancock had become enamored of his gold-braided colonel's uniform and had come to believe that his service on the Boston Common with the Corps of Cadets qualified him to be commander in chief. He all but grinned as he recognized his Massachusetts colleague John Adams to nominate the commander in chief of the Continental Army.

When John Adams rose, however, he had a different perspective from Hancock's. Adams had mingled discreetly among the delegates for several daysâsoutherners as well as northernersâlistening to and trying to understand every view and sentiment. There was little doubt that delegates from middle and southern colonies harbored “a jealousy against a New England Army under the Command of a New England General.” Connecticut delegate Eliphalet Dyer suggested that selecting a nonâNew Englander “removes all jealousies, more firmly cements the southern to the northern, and takes away the fear of the former lest an enterprising eastern New England gentleman, proving successful, might with his victorious army give law to the southern or western gentry.”

14

It was evident to all that George Washington had the most “skill and experience as an officer” of any candidate.

15

He had commanded the Virginia Regiment for nearly five years during the French and Indian War and acquired an intimate knowledge of both conventional and unconventional battle tactics. On June 10, John Adams of Massachusetts helped unite the North and the South by proposing Virginia's Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army. His interminable preamble, however, wearied all but President Hancock, who beamed approvingly with the certainty that he would hear his own name called when Adams reached the end of his oration. “I had no hesitation to declare,” John Adams later wrote, “that I had but one gentleman in mind for that important command, and that

was a gentleman from Virginia who was among us and very well known to all of us, a gentleman, whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents, and excellent universal character, would command the approbation of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union.”

16