America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (23 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Lincoln’s Evolution on Race

The issue of slavery was now intimately connected to the war effort. It was more important than ever that Lincoln walk a tight line. On one hand, it was important to please the loyal border states – Kentucky and Missouri especially – where slavery was legal. But on the other hand, Lincoln saw political gain to be had from restricting slavery in the South. In addition to helping stave off foreign intervention by European powers that abhorred slavery, Lincoln was urged by abolitionists like Frederick Douglass to allow blacks to fight for the Union.

As a hesitant first move, Lincoln signed a bill abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C., in April of 1862. The abolition of slavery in the Capitol was a topic that had been discussed for over a decade. Lincoln supported it during his single term in Congress. With the South seceded, there was little controversy over the issue.

Among other race-related issues, the Union Army organized its first African-American Regiment in July of 1862. Union Major General David Hunter impressed slaves in the South Carolina Sea Islands, and enlisted them in the Union Army. From this recruitment came an idea: Southern slaves could be of enormous aid to the Union effort. On Secretary of State William Seward's advice, Lincoln mulled over the idea of emancipating the slaves – in the Confederacy only – on these grounds. Lincoln could skirt its unconstitutionality by directly making emancipation a war aim, one that could theoretically drain the South of manpower while swelling the Union armies’ ranks. At the same time, Lincoln's effective ability to emancipate slaves in the Confederate states was essentially nonexistent. Lincoln thought over the idea for the month.

On July 22, 1862, Lincoln announced to his Cabinet that he planned to free the Confederate slaves, only after a major Union victory. The Emancipation Proclamation was born.

Antietam and the Issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation

President Lincoln restored General McClellan and removed General Pope after the second disaster at Bull Run, and McClellan, now commanding a mixture of men from his Army of the Potomac and Pope’s Army of Virginia, began a pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in Maryland. Knowing McClellan’s reputation for cautious, deliberate movements, Lee split his army to capture different objectives throughout Maryland, including Harper’s Ferry. But the North was about to have one of the greatest strokes of luck during the Civil War. With the help of the “Lost Order,” a lost copy of the Army of Northern Virginia’s marching plans that made it to General George McClellan, the Army of the Potomac confronted Lee’s army at Sharpsburg against Antietam Creek, with a critical part of Lee’s army still finishing off its capture of Harper’s Ferry.

The bloodiest day in the history of the United States took place on the 75

th

anniversary of the signing of the Constitution. On September 17, 1862, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia fought McClellan’s Army of the Potomac outside Sharpsburg along Antietam Creek. That day, nearly 25,000 would become casualties, and Lee’s army barely survived fighting the much bigger Northern army.

Although the battle was tactically a draw, it resulted in forcing Lee’s army out of Maryland and back into Virginia, making it a strategic victory for the North and an opportune time for President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Five days later, Lincoln announced to the world that on January 1

st

, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation would go into effect. Rebellious states were given 100 days to rejoin the Union, at which point they would not necessarily lose ownership of their slaves.

The Battle of Antietam and its result, the Emancipation Proclamation, were together a major turning point in the War. At the time, however, Lincoln was actually disappointed, despite having forced the Confederates from Union territory. He believed General McClellan was too timid. While he was victorious, Lincoln was disenchanted with McClellan's inability to pursue Lee's army further. Lincoln had hoped McClellan could give a knock-out punch to the Confederate Army, but he failed to deliver. He thus replaced McClellan with General Ambrose Burnside, though Burnside proved to be just as unsatisfactory. He was replaced in early 1863 by Joseph Hooker, who stayed in command for six months.

The Emancipation Proclamation also factored prominently into American foreign policy. France and Great Britain were flirting with the idea of diplomatically acknowledging the Confederacy. Great Britain relied heavily on Southern cotton for its textile industry. But the Proclamation and Battle of Antietam convinced them otherwise. Neither nation was particularly interested in getting involved militarily with the war, and Antietam threw the Confederacy's favorable military position into question.

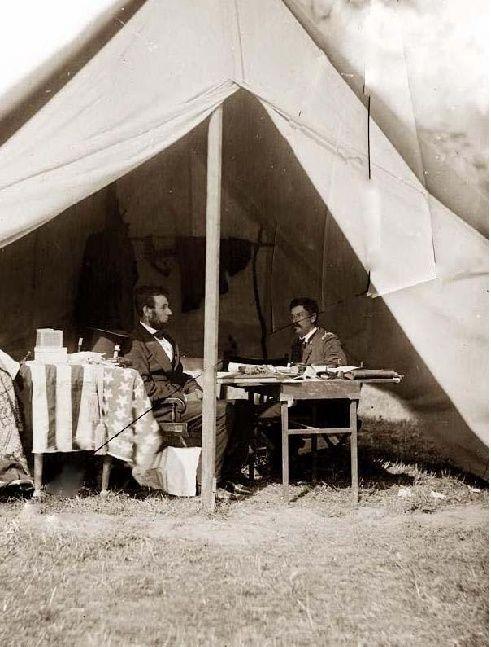

Lincoln and McClellan meet after Antietam

Chapter 6: Winning the Civil War, 1863-1865

Gettysburg

As the war continued into 1863, the southern economy continued to deteriorate. Southern armies were suffering serious deficiencies of nearly all supplies as the Union blockade continued to be effective as stopping most international commerce with the Confederacy. Moreover, the prospect of Great Britain or France recognizing the Confederacy had been all but eliminated by the Emancipation Proclamation. Given the unlikelihood of forcing the North’s capitulation, the Confederacy's main hope for victory was that Abraham Lincoln would lose his reelection bid in 1864, and that the new president would want to negotiate peace with the Confederacy.

After a stunning victory at Chancellorsville over the 100,000 strong Army of the Potomac, General Lee now believed that he could successfully invade the North again, and that his defeat before was due to a stroke of bad luck. Lee hoped to supply his army on the unscathed fields and towns of the North, while giving war ravaged northern Virginia a rest. Thus, Lee began plans for a second invasion of the North, which aimed to turn northern opinion against the war and against President Lincoln. Given the right circumstances, Lee's army might even be able to capture either Baltimore or Philadelphia and use the city as leverage in peace negotiations. Meanwhile, the loss at Chancellorsville led to Lincoln relieving General Joe Hooker, with George Meade assuming command of the Army of the Potomac just a few days before the Battle of Gettysburg.

Without question, the most famous battle of the Civil War took place outside of the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from July 1-3, 1863. Over those three days, nearly 8,000 would die, over 30,000 would be casualties, and the most famous attack of the war, Pickett’s Charge, would fail Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

Despite defeating Union forces during the first day of the battle, Confederate attacks on both flanks of the Union army failed to dislodge them from the high ground on the second day. Thus, on Day 3, Lee decided to make a thrust at the center of the Union’s line with about 15,000 men spread out over three divisions. Though it is now known as Pickett’s Charge, named after division commander George Pickett, the assignment for the charge was given to Longstreet, whose 1

st

Corps included Pickett’s division. Longstreet had serious misgivings about Lee’s plan and tried futilely to talk him out of it.

Lee’s decision necessitated a heavy artillery bombardment of the Union line and attempting to knock out the Union’s own artillery before beginning the charge that would cover nearly a mile of open space from Seminary Ridge to the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. What resulted was the largest sustained bombardment of the Civil War, with over 150 Confederate cannons across the line firing incessantly at the Union line for nearly 2 hours.

Unfortunately for Lee and the Confederates, the sheer number of cannons belched so much smoke that they had trouble gauging how effective the shells were. As it turned out, most of the artillery was overshooting the target, landing in the rear of the Union line. As Longstreet anticipated, the charge was an utter disaster, incurring a nearly 50% casualty rate and failing to break the Union line.

After the severe casualties at Gettysburg, General Lee was forced to retreat back to the South, never to invade the North again.

Vicksburg

Although Lee had frustrated the Union for most of 1862, the Civil War had been raging along the Mississippi River during that entire time, and things were going much better there for the Union. By 1862, the North controlled the Mississippi River down to Tennessee and had occupied New Orleans at the southern tip. Still, the Union had not yet achieved complete control over the Mississippi, which would cut the Confederacy in two. By 1863, Union gunboats and forces were able to clear the river until there was only one place on the Mississippi that the Confederacy still controlled: Vicksburg, Mississippi. Vicksburg was a heavily fortified town and Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant led a campaign in the summer months that turned into a siege of Vicksburg by May 1863.

As fate would have it, the Confederate forces in Vicksburg surrendered to Grant the day after Lee was defeated at Gettysburg. The siege had made Vicksburg’s residents so desperate that some civilians were forced to eat rats to survive. The Confederacy had now been cut in two, and it was dealt a double body-blow from which it never recovered.

The Gettysburg Address

When the crowd came to Gettysburg in November 1863 to commemorate the battle fought there 4 months earlier, they came to hear a series of speeches about the Civil War and the events of that battle. And although President Lincoln himself was coming to deliver remarks, he was not in fact the keynote speaker.

Instead, the man chosen to give the keynote speech was Edward Everett, a politician and educator from Massachusetts. Everett served as both a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator, and he was also the 15th Governor of Massachusetts, Minister to Great Britain, and United States Secretary of State. By the Civil War, he was considered perhaps the greatest orator in the nation, making him a natural choice to be the featured orator at the dedication ceremony of the National Cemetery in Gettysburg in 1863.

Everett is still known today for his oratory, but more for the fact that he spoke for over two hours at Gettysburg, immediately before President Lincoln delivered his immortal two-minute Gettysburg Address. Everett immediately recognized the genius in Lincoln’s speech, writing to the President, "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

Perhaps Lincoln’s most impressive feat is that he was able to convey so much with so few words; after Everett spoke for hours at Gettysburg, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address only took a few minutes, but in those few minutes, Lincoln invoked the principles of human equality espoused by the Declaration of Independence and redefined the Civil War as a struggle not merely for the Union, but as "a new birth of freedom" that would bring true equality to all of its citizens, ensure that democracy would remain a viable form of government, and would also create a unified nation in which states' rights were no longer dominant. And yet, despite the speech's prominent place in the history and popular culture of the United States, the exact wording of the speech is disputed. The five known manuscripts of the Gettysburg Address differ in a number of details and also differ from contemporary newspaper reprints of the speech.

At the time, few Americans knew the President had even given a speech at Gettysburg. The Address was not covered in newspapers. But today, the Gettysburg Address goes down in history as a concise and eloquent oration about the very purpose of the United States. Almost all American schoolchildren today can recite the phrase “Four Score and Seven Years Ago..”