America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (29 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Grant’s army had just won the biggest battle in the history of North America, with nearly 24,000 combined casualties among the Union and Confederate forces. Usually the winner of a major battle is hailed as a hero, but Grant was hardly a winner at Shiloh. The Battle of Shiloh took place before costlier battles at places like Antietam and Gettysburg, so the extent of the casualties at Shiloh shocked the nation. Moreover, at Shiloh the casualties were viewed as needless; Grant was pilloried for allowing the Confederates to take his forces by surprise, as well as the failure to build defensive earthworks and fortifications, which nearly resulted in a rout of his army. Speculation again arose that Grant had a drinking problem, and some even assumed he was drunk during the battle. Though the Union won, it was largely viewed that their success owed to the heroics of General Sherman in rallying the men and Don Carlos Buell arriving with his army, and General Buell was happy to receive the credit at Grant’s expense.

Grant himself was not above playing the blame game. Miscommunication between Grant and division commander Lew Wallace resulted in Wallace failing to properly march his men into the fight while the Confederates were advancing on the first day. For the rest of his life, Grant blamed Wallace for the failure, but historians do not believe the miscommunication was actually his fault. Nevertheless, with Grant and Halleck heaping the blame Wallace for the near loss at Shiloh, it permanently tarnished Wallace’s military career, and he was removed from his command in June 1862. Still, it’s likely that any military accomplishments Lew Wallace may have lost out on during the Civil War would have been eclipsed by his authorship in 1880 of the classic

Ben-Hur

anyway.

Although Halleck agreed with Grant that Lew Wallace deserved the blame Grant was giving him, Grant was ultimately the fall guy. As a result of the Battle of Shiloh, General Halleck demoted Grant to second-in-command of all armies in his department, an utterly powerless position. And when word of what many considered a “colossal blunder” reached Washington, several congressmen insisted that Lincoln replace Grant in the field. Lincoln famously defended Grant, telling critics, “I can’t spare this man. He fights.”

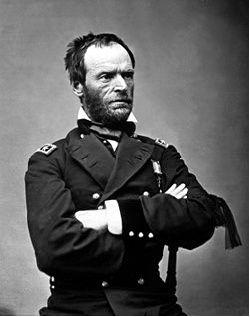

Lincoln may have defended Grant, but he found precious few supporters, and the negative attention bothered Grant so much that it is widely believed he turned to alcohol again. While historians still debate that, what is known is that he considered resigning his commission, only to be dissuaded from doing so by General Sherman. Sherman had experienced the same career path as Grant, with failed business ventures, a stint in the Mexican-American War, early success in the Civil War and then a failure that nearly cost him his career (in Sherman’s case, a nervous breakdown). As Sherman would later note, he supported Grant when Grant was drunk, and Grant supported him when he was crazy.

Sherman

Although Grant stayed in the army, it’s unclear what position he would have held if Lincoln had not called Halleck to Washington to serve as general-in-chief in July 1862. At the same time, Halleck was given that position in large measure due to Grant’s successes in the department under Halleck’s command. Thankfully for the Union, Halleck’s departure meant that Grant was reinstated as commander.

General Orders No. 11

When Grant reassumed command, the Union forces in the west were still intent on taking control of the entire Mississippi River, which would have the effect of cutting the Confederacy in two. With Grant’s early victories in the war and the Union capture of New Orleans, Grant was reinstated to command at a time when the Confederates’ last stronghold on the Mississippi River was at Vicksburg. After Union forces under General William S. Rosecrans defeated Confederates at Iuka (September 19) and Corinth (October 3--4),

Grant’s eventual capitulation of Vicksburg is considered one of the turning points of the Civil War, but his initial attempts to advance towards Vicksburg met with several miserable failures. First, Grant’s supply base at Holly Springs was captured. Then an assault launched by Union General Sherman at Chickasaw Bayou was easily repulsed by Confederate forces, with serious Union casualties resulting. Grant then attempted to have his men build canals north and west of the city to facilitate transportation, which included grueling work and disease in the bayous.

Suffering this series of setbacks greatly frustrated Grant, who issued one of the most notorious orders of the war in December 1862. Annoyed that cotton and gold were being successfully smuggled throughout the Department of the Tennessee, Grant issued General Orders No. 11, which banned Jews from being in the department. Referring in a letter to “Jews and other unprincipled traders”, the text of Grant’s General Orders read:

“1. The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department [of the Tennessee] within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.

2. Post commanders will see to it that all of this class of people be furnished passes and required to leave, and any one returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from headquarters.

3. No passes will be given these people to visit headquarters for the purpose of making personal application of trade permits.”

Grant’s department began forcibly removing all Jews from the territory, but it caused such an uproar that Lincoln had Grant personally rescind it within 3 weeks of its issuance. Until his dying days Grant would make several excuses for the order, at one point claiming it was drafted by a subordinate and he signed it without reading it, and at another point claiming that he was following orders from Washington. The order would haunt Grant after the war, and for his part he would spend the rest of his life trying to prove he was not an anti-Semite, going on to employ a record number of Jews during his presidency and becoming the first president to attend a synagogue service.

Capturing Vicksburg

Finally, on April 30, 1863, Grant finally launched the successful campaign against Vicksburg, marching down the western side of the Mississippi River while the navy covered his movements. He then crossed the river south of Vicksburg and quickly took Port Gibson on May 1, Grand Gulf on May 3, and Raymond on May 12. Realizing Vicksburg was the objective, the Confederate forces under the command of Pemberton gathered in that vicinity, but instead of going directly for Vicksburg, Grant took the state capital of Jackson instead, effectively isolating Vicksburg. Pemberton’s garrison now had broken communication and supply lines. With Grant in command, his forces won a couple of battles outside Vicksburg at Champion Hill and Big Black River on May 16 and 17, forcing Pemberton’s men into Vicksburg and completely enveloping it. When two frontal assaults were easily repulsed, Grant and his men settled into a nearly two month long siege of Vicksburg.

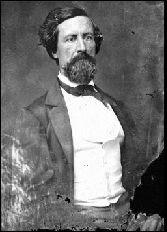

Pemberton

The siege was apparently trying on Grant, who historians believe went on a two day bender during the siege, but it was even harder on the residents of Vicksburg. Completely choked off, people began to starve, with many eating rats to survive. Jefferson Davis and his top military brass were unable to determine how best to relieve Vicksburg and Pemberton, who was widely viewed as an abject failure.

The end finally came on July 4, 1863, with Pemberton surrendering Vicksburg and its nearly 35,000 man garrison. Coincidentally, the surrender of Vicksburg came a day after the Army of the Potomac scored a critical victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in the East, which has widely overshadowed the Vicksburg campaign in Civil War history. Despite the dazzle of Gettysburg, what Grant had accomplished in the span of two and a half months not only cut the Confederacy in half, it made him the most important field general in the Union Army.

Still, Grant was widely suspected of being drunk during the Vicksburg campaign. Lincoln personally wrote a letter to Grant “as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done the country”, but he also sent Charles Dana to investigate accusations of Grant’s drunkenness. Dana would eventually befriend Grant, which helped Grant deflect any blame or criticism for drinking.

Chattanooga

Grant had little time to personally celebrate Vicksburg. On September 19-20, 1863, the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Braxton Bragg decisively defeated General Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga. Rosecrans committed a blunder by exposing a gap in part of his line that General James Longstreet drove through, sending Rosecrans and nearly 20,000 of his men into a disorderly retreat. The destruction of the entire army was prevented by General George H. Thomas, who rallied the remaining parts of the army and formed a defensive stand on Horseshoe Ridge. Dubbed “The Rock of Chickamauga”, Thomas’s heroics ensured that Rosecrans’ army was able to successfully retreat back to Chattanooga.

Once the Union forces reached Chattanooga, however, it was the Confederates’ turn to lay siege, with Bragg’s army mostly encircling the city. On October 17, 1863, Grant was given command of the Military Division of the Mississippi which included the departments of Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee, and instructed to relieve Chattanooga.

What followed were some of the most amazing operations of the Civil War. Grant relieved Rosecrans and personally came to Chattanooga to oversee the effort, placing General Thomas in charge of reorganizing the Army of the Cumberland. Meanwhile, Lincoln detached General Hooker and two divisions from the Army of the Potomac and sent them west to reinforce the garrison at Chattanooga. However, Grant instead used Hooker’s men to establish the “Cracker Line”, a makeshift supply line that moved food and resources into Chattanooga from Hooker’s position on Lookout Mountain.

In November 1863, the situation at Chattanooga was dire enough that Grant took the offensive in an attempt to lift the siege. By now the Confederates were holding important high ground at positions like Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. First Grant ordered General Sherman and four divisions of his Army of the Tennessee to attack Bragg’s right flank, but the attempt was unsuccessful. Then, in an attempt to make an all out push, Grant ordered all forces in the vicinity to make an attack on Bragg’s men.

On November 24, 1863 Maj. Gen. Hooker captured Lookout Mountain in order to divert some of Bragg’s men away from their commanding position on Missionary Ridge. But the victory is best remembered for the almost miraculous attack on Missionary Ridge. General Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland singlehandedly delivered the stunning victory by storming over Missionary Ridge, and forcing the Confederate army into a disorganized rout. In doing so, the men had actually defied Grant’s orders. Grant, initially upset, had only ordered them to take the rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge, figuring that a frontal assault on that position would be futile and fatal. The Army of the Cumberland had essentially conducted the most successful frontal assault of the war spontaneously. While Pickett’s Charge, still the most famous attack of the war, was one unsuccessful charge, the Army of the Cumberland made over a dozen charges up Missionary Ridge and ultimately succeeded.

The victory at Chattanooga increased Grant's fame throughout the country. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General, a position that had only been awarded to George Washington and Winfield Scott.

General-in-Chief

Although the Army of the Potomac had been victorious at Gettysburg, Lincoln was still upset at what he perceived to be General George Meade’s failure to trap Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in Pennsylvania. When Lee retreated from Pennsylvania without much fight from the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln was again discouraged, believing Meade had a chance to end the war if he had been bolder. Though historians dispute that, and the Confederates actually invited attack during their retreat, Lincoln was constantly looking for more aggressive fighters to lead his men.