America's Prophet (31 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

IN WASHINGTON, MOSES

doesn’t just live in the White House. His statue stands in the Library of Congress. His tablets are embedded in the floor of the National Archives. And his face appears in the House chamber, along with that of Hammurabi, Maimonides, and Napoléon, in a tribute to twenty-three figures who inspired American law. Eleven of the bas-reliefs face left, and eleven face right; they all look toward Moses, who hangs in the middle, the only one shown full-figured.

Perhaps the most surprising Mosaic representations in the capital are the

six

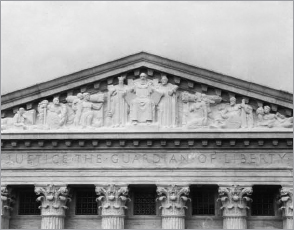

in the nation’s highest court. Moses is practically the mascot of the U.S. Supreme Court. He appears at the center of the east pediment, flanked by Solon of Athens and Confucius of China in a tribute to the legal traditions of other civilizations. He appears in the gallery of statues that leads into the court, as well as the south frieze in the chamber. The Ten Commandments are displayed on the bronze gates leading into the courtroom as well as on the interior panels of the chamber doors.

Are these depictions an anachronism, or do they still speak in America today?

To answer that question I spoke to two of the most vocal combat

ants in church-state cases before the Supreme Court—Rabbi David Saperstein of Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism and Jay Sekulow of Pat Robertson’s American Center for Law and Justice. Saperstein, who descends from a long line of rabbis, has been called the “quintessential religious lobbyist.” Sekulow, who was born a Jew but converted to Christianity, has been deemed “the Almighty’s Attorney-at-Law.” Both men presented briefs in the two Ten Commandments cases that appeared before the Court in 2005. The first reviewed whether a granite Ten Commandments on the grounds of the Texas Capitol violated the establishment clause of the First

Amendment; the second examined whether government-sponsored displays of the Ten Commandments in Kentucky courtrooms violated the same clause.

East pediment of the Supreme Court of the United States, with Moses seated in the center, holding the tablets of the law.

(Courtesy of The Supreme Court of the United States)

Saperstein was against displaying the commandments because he sees them as “unambiguously religious.” Unlike “God Bless America” or “In God We Trust,” both of which are part of the “background sounds of American life,” the Decalogue promotes specific religious traditions. Sekulow argued that displaying the Commandments does not endorse one faith but honors their “extraordinary influence” on American law. The Ten Commandments are like other expressions of America’s cultural heritage, including Thanksgiving and “one nation under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance.

In the Texas case, the Court agreed with Sekulow, ruling that the commandments were donated by a civic group and did have the secular purpose of reducing juvenile delinquency, while in Kentucky, the Court found the displays had no such purpose and had to be removed. In yet another cultural civil war, Moses had somehow found a way to survive. When he is aligned with America’s secular tradition, he can stand on public ground. When he assumes the role of religious prophet, he must remain on private property.

“There are two different narratives in America,” David Saperstein explained. “The Enlightenment and the religious. ‘I think therefore I am’ versus ‘In the beginning was God.’ And there was no day that Western civilization went to the polls and said, ‘That’s it for the God-oriented world. We’re going with the rationalist world.’ We’re an amalgam of all these things.”

“So where is the balance of power today?”

“I think it’s a dead heat. I think the American people believe in the Ten Commandments and don’t like the idea that the government can say, ‘Don’t post them in some place.’ But I think the American people don’t like the idea of government imposing religious mes

sages and values.” In 1776, I mentioned, America was clearly a biblical nation. The same could be said of 1865, and probably even 1932. “Is America a biblical nation today?”

“Ninety-six percent of Americans say they believe in God,” Rabbi Saperstein said. “Eighty-five percent say that religious values are important in their lives. People cherish the Bible, but I think there is a comfort level with functionally separating government and religion. So it is a biblical nation in terms of amorphous values that people trace back to the Bible, but the idea that government should somehow impose the Bible on others is becoming increasingly troublesome for Americans.”

Jay Sekulow agreed. “I think we’re a religious nation,” he said. “I think our institutions presuppose the existence of a supreme being. But are we a biblical nation? I think that’s a harder question right now, because I think we’ve moved away from involving the Bible in government. The Bible is still present in America, but it’s muted.”

“So is America weaker because of that muting?”

“I think if we lose our religious underpinnings, we lose our compass. And not just because of abortion and same-sex marriage. That includes decency, how we view the poor, helping those in need. The biblical overtones in all those are significant, and if we lose that, we lose something about our culture.”

One irony of this decline in biblical influence is that it forces combatants like Saperstein and Sekulow into a shared allegiance. They may disagree about the degree of religion’s involvement in contemporary American life, but they absolutely agree that the Bible forms one of the main threads of the country’s DNA. And I couldn’t help wondering if that alliance might provide an opening to crack the cultural gridlock the country faces. As I had found, one biblical story has served as a touchstone for all Americans. Could under

standing the role of Moses in American history illuminate the changing role of faith in our national life? Could Moses restore some of the civility that both left and right say is missing?

Could all those marble Moseses scattered around the nation’s capital remind us of our shared heritage of freedom and law?

“I think so,” said Jay Sekulow. “Christians, by nature, accept the biblical story of Moses with no hesitation. It’s a political story. Jesus, on the other hand, was above politics. His was a kingdom not of this world. Plus, if you look at the way Moses approached issues and leadership, there’s a great example there. Moses never presumed he had the complete allegiance of the people. He operated under the assumption that you had to maintain people’s allegiance.”

David Saperstein said: “I believe he can, because every generation is a new generation. So every generation is reinspired by the narrative. Every generation feels that if we march down the right path, we can really make it to the Promised Land. The difference now is that our generation faces threats so lethal to our planet that they can truly alter human history. This is the generation that has to make it to the Promised Land. This generation truly needs a Moses.”

BEYOND HIS ROLE

in politics, Moses also plays a part in what may be the country’s larger conversation: the path to personal fulfillment. During our visit to Boston, I slipped out one morning to meet one of the most famous Jews in the city (after Kevin Youkilis, the Red Sox first baseman, and Bob Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots). Harold Kushner was a little-known suburban rabbi in 1981 when he wrote a book inspired by the loss of his first child, Aaron, from a rare genetic disease that produces premature aging.

When Bad

Things Happen to Good People

became one of the most influential books of popular theology in American history, selling more than four million copies and making the soft-spoken Brooklyn native America’s rabbi-in-chief.

Kushner went on to write numerous pastoral books, and one of them,

Overcoming Life’s Disappointments,

published in 2006, uses the story of Moses to explore how individuals can cope with personal crisis. “What was the wisdom of Moses that enabled him to carry on day after day, year after year, as leader of a people who exasperated him more often than they appreciated him?” Kushner asked. “It was a recognition of the frailty of the human character, the occasional unreliability of even the best of people, and the sometimes unexpected goodness of even the worst of them.”

Moses has long been a pivotal figure in the mixing of psychology and religion, beginning with Sigmund Freud. The founder of psychotherapy had a lifelong fascination with Moses, and in his final book,

Moses and Monotheism,

published in 1939, he portrays the leader of the Israelites as the father figure of Western thought. Freud contended that Moses was a renegade Egyptian priest, who led a rebellious group of monotheists into the desert. The former slaves could not handle the burdens of a new faith and murdered Moses, then repressed their crime. The memory of the murder returned over time in the form of respect for morality, ethics, and other “intellectual” ways of relating to God. This interest in ideas over idolatry and sensuality became the centerpiece of Western civilization.

In 1946, Joshua Liebman, another Boston rabbi, published one of the first pop-psychology mega-sellers,

Peace of Mind,

which argued that spiritual health was related to psychological maturity. Of Americans’ obsession with material success, he wrote, “We are still like the Children of Israel dancing around the golden calf. Psychology today

can aid religion in giving many people insights into the reason for this neurotic idolatry.” In the 1990s, Promise Keepers, the evangelical men’s movement, trumpeted Moses as the ultimate role model, a “man’s man [who] was God’s man.” “For Moses, the call was to lead a nation,” wrote one of the group’s leaders, “whereas your call and mine will likely be less visible. But make no mistake, we

are

leaders!” Even the 1998 animated film

Prince of Egypt

presents Moses as a confident youth showered with love and his rival, Rameses, as starved for fatherly attention. “All he cares about is your approval,” Moses tells the pharaoh about Rameses.

Is this what Moses has become in America—a self-help guru?

“In many ways, yes,” Rabbi Kushner said. “There is still a population of immigrants for whom America represents leaving Egypt and coming to a better life. And there are minorities—blacks, Asians, Hispanics—who are teaching us what it means to be American today. But there is a phenomenon going on in this country. For the first time there’s a generation of Americans growing up who cannot look forward confidently to being more successful than their parents. The American promise always was: You can outdo your parents. But we have a generation of parents—my generation—who are so well educated and so successful they leave very little room for their children to outstrip them. And I think that’s a psychological need, especially for males. So what a lot of people are doing is redefining success, saying things like, ‘Okay, I’m not going to make as much money as my father made, but I’m going to have my priorities straight. I’m not going to be so busy I can’t watch my kids at a dance recital.’ I think they’re redefining the Promised Land. And I think Moses becomes the one who shows the way.”

“How?”

“He sets an example. As you know, the biblical name for Egypt

means ‘the confining place.’ So both in geographical terms and individual terms, Moses resonates with the idea of leaving the confinement of Egypt and heading out into the desert. You’ve left the confinement of parents, upbringing, hometown, expectations. You may even have made it across the desert. But you’re not going to find the Promised Land you envisioned when you started out. How do you define fulfillment? Come up with your own sense of promised land. That’s what Moses calls people to do.

“I had occasion just a few weeks ago to speak to a woman who’s recently gone through a divorce,” Rabbi Kushner continued. “She was very uncomfortable about facing Passover for the first time without the husband that she had shared the occasion with for years. I said, ‘See it as a Passover story—that you’re leaving a belittling, confining situation. It’s scary to go out into the desert, but the desert is something you have to get through to find the reward at the other end.’ There’s something universal, and something specifically American, about that.”

“There’s a risk in what you’re saying,” I mentioned. “The risk is that you become so involved with your own personal drama that you forget that caring for others is a central part of the story.”

“Perhaps, but look at what Moses does when he realizes that everyone else is going to the Promised Land and he isn’t,” Rabbi Kushner said. “He doesn’t go off and sulk. He doesn’t go somewhere for counseling. He gathers the people together on Mount Nebo and prepares them for what they will face in the future. In the Jewish tradition, we speak of him as Moses

Rabeinu

—Moses, Our Teacher—not Moses, Our Political Leader; not Moses, Who Freed the Slaves. Moses, Our Teacher. He dedicates himself to getting the people to embrace the ideas that they have to live by when he’s no longer around to remind them.

“The example I gave before,” he said. “The no-longer-young man

who says, ‘Okay, I’ll never earn the amount of money my father earned.’ Where does he find his fulfillment? In being a better father. In being a better husband. That’s not narcissism. That’s not saying, ‘I’m going to spend my sixteen hours of wakefulness figuring out how I can make myself a success.’ That is defining success as caring for other people.”