An Act Of Murder (28 page)

Authors: Linda Rosencrance

There was a variety of medical testimony at trial, including testimony from Dr. Neil Meade, a family-practice physician who last saw Steve eighteen months before his death, Biddle told Friedlander. Meade prescribed medication for Steve for a rash and insomnia and also provided him with a patch to help him stop chewing tobacco.

“The principal reason to call him seemed to be to show that the deceased did not smoke tobacco, which based on the presence of cigars in the room in which he died, was possibly a cause of the fire,” Biddle wrote.

Biddle told Friedlander that David Fowler, the medical examiner who performed the autopsy, was the state's chief medical witness. Fowler testified that the low carbon monoxide levels in Steve's blood showed that he died before the fire started because he did not breathe any of the products of the fire. Fowler testified that the absence of soot in Steve's nose, mouth, trachea, windpipe, and lungs also confirmed that Steve died before the fire reached him. Biddle told Friedlander that Fowler admitted that there was nothing in the toxicology results that indicated the cause of Steve's death. Biddle explained that because Steve worked on a golf course, Fowler claimed he looked for evidence that Steve's death was caused by overexposure to pesticides, but there was nothing to indicate that was the case.

Biddle said Fowler admitted there was an issue with Steve's “q” waves something that couldn't be confirmed without a stress EKG, which Steve never tookâalthough he was told to get one.

The prosecution also called FBI toxicologist Marc LeBeau, who tested Steve's blood and urine for the presence of succinycholine, but didn't find any, Biddle said. Barry Levine, the toxicologist for the medical examiner's office, tested for the presence of alcohol in Steve's blood and found that the level was normal.

In contrast to the numerous experts paraded out by the prosecution, the defense called only one key expert, Dr. John Adams, who told the jury that the cause of death should have been listed as unknown on the autopsy report. Adams also testified that the type of fire was consistent with fatal fires where death occured despite a low level of carbon monoxide in a deceased's blood, Biddle said. In addition, Adams told the jury that given the mechanics of injecting succinylcholine, Kim couldn't have injected Steve with the drug without his cooperation, Biddle told Friedlander.

At Kim's hearing Friedlander, who had gone over Dr. Fowler's autopsy results, testified that the autopsy alone was not enough to rule out natural causes. Friedlander said Fowler did not record the condition of Steve's heart during the postmortem and also couldn't determine the exact cause of his death.

At the two-day hearing in June, Biddle called Kim's lawyers, Harry Trainor and Bill Brennan, to the stand to ask them about the decisions they made to call or not call certain experts during Kim's trial.

Now, five-and-a-half years after Kim's conviction, Brennan and Trainor talked about their preparation for her trial.

“As part of our trial preparation we went down to Harbourtowne and went into the actual room where the fire occurred and examined it with our investigator. We took photographs. We did that type of on-scene, hands-on investigation in the case,” Brennan said. “The issue in this case was the cause of death of Mr. Hricko. The medical examiner of the state of Maryland basically opined that Mr. Hricko was an other wise healthy individual. He said there was no sign of cancer, no sign of heart disease, no sign of any other illness that would have killed him. So we were faced with an otherwise healthy thirty-five-year-old individual who died suddenlyâwhat causes thatâwas there a criminal agency behind that or was it a natural death? So the ME said they did a complete autopsy and all of his organs were otherwise healthy. We called Dr. Adams to show that this flash fire would have caused heat to go down his lungs and cause his sudden death and it wouldn't necessarily leave a lot of charring. I believe that was the issue we had Dr. Adams opine on.”

However, the defense team had another expert who worked with them on the case, according to Trainor.

“That was our fire reconstruction expert who worked for us, consulted with us, and advised us, but did not testify,” Trainor said. “Why didn't he testify? Well, we liked where the facts wereâyou don't call an expert to testify if his opinion would not change the facts.”

Brennan said, “I think the fact that the judge wouldn't let the state fire marshal opine that it was an incendiary fireâthat it was a set fireâand once the judge struck that opinion and wouldn't let him give that opinion, that's about as good as we were going to get on that issue.”

Trainor said there was a strategic element to not putting their fire expert on the witness stand.

“If we put our expert on, then Mr. Dean would have had him on cross-examination and could have asked him leading questions on that issue and we open up that issue that we've already closed,” Trainor said. “We certainly wouldn't put on someone and open him up to cross-examination on an issue that has already been closed by the judge in our favor.”

As far as the cause of Steve's death, Brennan said there was no evidence of succinylcholine in Steve's body.

“We clearly objected at trial that the medical examiner was speculating that it was poison because there was no evidence of succinylcholine,” Brennan said. “And it was pure speculation that a poisoning or something caused the death because there was no scientific or medical evidence to substantiate that opinion. I remember cross-examining him on it, saying he was considering things outside the record to arrive at his opinion that it was poisoning. But I think he said if he confined his examination to just the science or the medicine, there really was no cause of death. But when the medical examiner looked beyond the medicine and took into consideration all the other stuff, he then got to poisoning as the cause of death.”

Brennan said, “I think our legal issue was you're the doctor, you confine it to medicine or you confine it to science, then tell us what you have. I think if he confined it to that, he wouldn't know what killed Steve. The law in Maryland is that the medical examiner can look beyond the science and consider other issues. We were fighting over that issue, but the appellate court judge ruled that the medical examiner could look beyond the pure science and get into other issues. Our objection was that once he got beyond the pure science, he was making value judgments as to who was telling the truth; who was not telling the truth; was succinylcholine really used? There was absolutely no evidence that there was any succinylcholine in Mr. Hricko's body.”

In a ruling dated November 4, 2004, Judge Price denied Kim's request for a new trial. Price ruled that Kim was not denied effective counsel during her trial. Price said according to case law a defendant must show that the performance of her lawyer “fell below the standard of reasonableness under prevailing professional norms.” And if a lawyer's performance was ruled professionally unreasonable, then the defendant must also show that there was reasonable probability that the result of her trial would have been different.

In both cases Judge Price ruled that the actions of Kim's attorneys at trial were not unreasonable, but even if their decisions had been unreasonable, the outcome of the trial would not have changed.

Despite the unfavorable outcome of the hearing for a new trial, Kim still has a sliver of hope that her sentence could be reduced.

“After Kim was convicted and sentenced, we did file a motion for reconsideration of sentence, which is still pending [as of this writing],” Trainor said.

Under Maryland law, trial attorneys can file a motion within ninety days of sentencing asking the judge to modify or reduce the sentence, Trainor said.

“That has been taken under advisement by the judge, and, as far as I know, is still pending and could, in the future, mean she might get a hearing on that motion,” he said. “The law is in flux, but, as it stands right now, I believe the judge can act on it almost at any time in the future.”

However, the law has been changed since Kim was sentenced, Brennan said.

“As of July 1, 2004, the law changed and now the court only has five years to modify a sentence. Prior to that, there was no limit and the judge can hold it for one year, five years, or ten years,” Brennan said.

“When you look at Kim's sentenceâJudge Horne sentenced her to life in prison because she was convicted of first-degree murderâalthough he wouldn't be able to change the life imprisonment sentence, he would be able to suspend some portion of it,” Trainor said. “That means he'd have the power, if he chooses to exercise that power, to change it to a life sentence and suspend all but a set term of years, but it hasn't yet been ruled on, as far as I know.”

As it stands, Kim is eligible for parole consideration after fifteen years, less good time, but the judge has the authority to suspend any portion of that, Brennan said.

“He could suspend all but thirty years, or all but twenty-five years of her sentence, but it's purely at the judge's discretion,” he said. “But that motion is still pending.”

In December 2004, Kim also filed an application for leave to appeal to the Maryland Court of Special Appeals asking that the court take another look at her case. Such requests are called applications for leave to appeal because the granting of a hearing by the Court of Special Appeals is discretionary, not mandatory. Kim filed this application “pro se,” or representing herself, because Biddle, who prepared the application for her as a gesture of good will, said he couldn't continue to represent her because she couldn't pay him.

The Court of Special Appeals denied Kim's request for leave to appeal. After Kim's friend Rachelle St. Phard put up an additional $22,500, Biddle filed a post conviction petition for relief of the state court's decision in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Richmond, Virginia. Biddle told Kim he planned to argue that state court's denial of her appeal was based on an unreasonable interpretation of the federal ineffective assistance of counsel law. That petition was pending as of this writing.

Cathy Rosenberger, however, isn't so sure anything is ever going to help Kim.

“Through this entire legal process with Kim I have learned so much about the legal system,” she said in a letter to Robert Biddle. “From an outsider it looks like a âgood old boys club.' The members of the club consist of judges, police, prosecutors, medical examiners and investigators.”

Still firmly believing that Steve died accidentally in the fire at Harbourtowne, Rosenberger said the exact details of his death would always remain a mystery. In the beginning, Rosenberger said she had faith in the system and thought if a person presented enough reasonable doubt people would listen.

“That's why I put up about $40,000. But I stopped contributing because it doesn't appear to me that there is any way that a judge is going to listen,” she wrote. “Even if we uncovered the exact cause of death, the judges would turn a deaf ear,” she continued. “After sitting through Kim's trial and hearingsâI have watched a total of five judges during proceedingsâ[judging by] their facial expressions and body language it was so obvious to me that they are practically laughing at us. The smirking, rolling eyes, smiling, etc., [sent] a very clear message [to us].”

Loyal to the bitter end, Cathy Rosenberger is unwilling to accept the meaning behind that messageâthat Kim Hricko did, in fact, kill her husband.

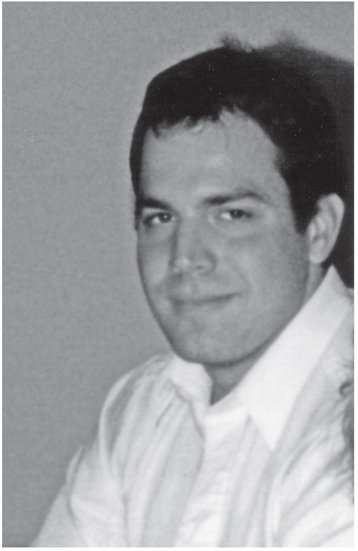

A young Stephen Hricko.

(Court file photo)

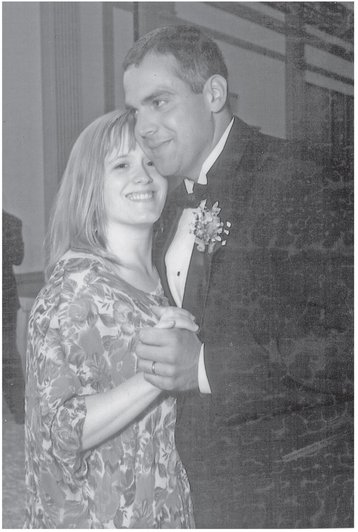

Kimberly and Stephen Hricko in happier times.

(Court file photo)

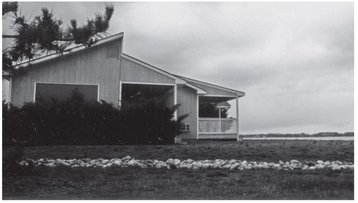

Stephen Hricko died in room 506 in this cottage at Harbourtowne Resort.

(Photo courtesy of

The Baltimore Sun

)

The Baltimore Sun

)

This is what the Hrickos' room would have looked like before the fire.

(Court file photo)

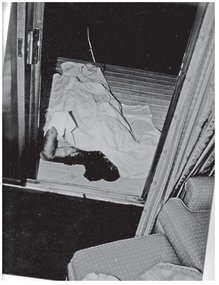

The Hrickos' room after the fire.

(Court file photo)

The wood stove with doors open in the Hrickos' room after the fire.

(Court file photo)

The

Playboy

magazine and pillow found in the Hrickos' room after the fire.

Playboy

magazine and pillow found in the Hrickos' room after the fire.

(Court file photo)

The package of cigars and other items found in the Hrickos' room.

(Court file photo)

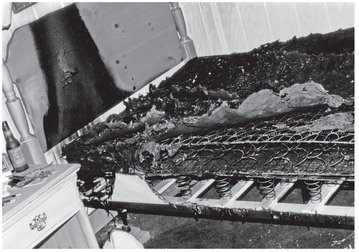

The burned bed with the scorched headboard, as well as items on the bedside table in the Hrickos' room.

(Court file photo)

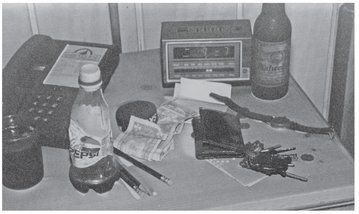

Items found on the bedside table in the Hrickos' room after the fire.

(Court file photo)

The burned bed in the Hrickos' room.

(Court file photo)

Stephen Hricko's burned arm.

(Court file photo)

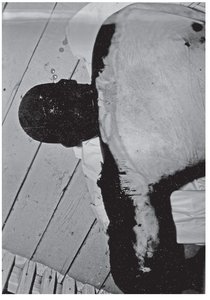

The back of Stephen Hricko's burned body.

(Court file photo)

Other books

Never Mind Miss Fox by Olivia Glazebrook

A Wind of Change by Bella Forrest

Three's a Crowd (From the Files of Madison Finn, 16) by Dower, Laura

Mosquito by Roma Tearne

A Wild and Lonely Place by Marcia Muller

Gruffen by Chris D'Lacey

Courting the Countess by Barbara Pierce

Sabotaged by Margaret Peterson Haddix

The Flesh Eaters by L. A. Morse

The Kidnapper by Robert Bloch