An Appetite for Violets (9 page)

Read An Appetite for Violets Online

Authors: Martine Bailey

That night my mistress said I must wait at table in the private parlour. I was all fingers and thumbs while my stomach growled from smelling the lamb, brisket, and duck. No sooner had my lady, Jesmire and Mr Pars gone away, than me and Mr Loveday attacked the broken food. The leavings were even tastier for being half-cold; the lamb was sweet and pink and studded with salty capers.

‘Where is it you are coming from, Mr Loveday?’ I asked between mouthfuls. ‘China or Africa?’

He licked his gleaming teeth. ‘You never travel, Miss Biddy, that for sure. I come from island past Batavia, white people got no name my place. Island of fire.’

Later, when he was sharing out the last of the cheese, he looked at me all sheepish. ‘Miss Biddy, you say we servant be friends?’

I told him that was true.

‘I go back home one day,’ he said, raising his sloe-black eyes. ‘I go back my wife and son.’

‘You must take care what you say,’ I said in a hushed tone, ‘for Lady Carinna owns you now.’

‘She own me,’ he said, looking truly miserable. ‘But maybe she lose me, Miss Biddy? You think a man ever get lost and be forgot?’

‘Maybe. But it would be a crime to purposely lose yourself. It would be stealing valuable property. You could be hung for it.’

‘What that mean?’

So I told the poor lad of the gallows, and how the crowds flock to see a body twitch and die. He looked so afeared to hear of it, I squeezed his arm.

‘You take care now, Mr Loveday,’ I said, ‘and confide your notions to me before you carry out any daft nonsense.’

He nodded and we left it at that, for Mr Loveday was my only friend now, and we had to look out for each other.

* * *

Later, I saw an old waiter make a brandy posset by the parlour fire and made a memory of the whole receipt, for Her Ladyship said she liked it. I tasted a little of the dregs by offering to carry the posset pot back to the kitchen. It was light and sweet and warmed the body as a brass pan warms a chilly bed. And so, having no other duties that night, I went to my closet and unknotted my bundle and took some sad pleasure in looking over my goods. Not being sure yet what I should write down I began with this list of all I had in the world:

A comb

A petticoat

A flannel gown

My nightcap and another day cap

One shift

A pink ribbon given me by Jem at Chester Fair

Lady Maria’s silver knife on a chain

A Prayer book inscribed by Widow Trotter

A picture cut from a newspaper that recollects my mother’s face

The Household Book called The Cook’s Jewel wrapped in a fustian piece

Quills and ink a gift from Mrs Garland

My sewing bag containing precious locks of hair wrapped in a linen cloth

Stockings and strings

One pound, three shillings and threepence halfpenny

The Red Silk Gown and petticoat given me by Lady Carinna

Next I wrote the making of the Brandy Posset down. Then, laying down I thought of Jem so far away back down the benighted road and wished sorely I had left him on better terms. But in a few blinks of an eye I slept as sound as a dormouse.

Loveday blinked and then closed his eyes, feeling water stream down his cheeks like unstoppable tears. He was perched on the back footboard of the carriage, shaken by every rut and rock in the broken road. The rain was dripping inside his collar, chafing his old wound so it ached without end. This was the coldest place he had ever known. Sometimes he was sure he would die soon, but his bones did not fail, nor his hair turn white. For some strange purpose his ancestors were keeping him alive in this terrible place.

He had already been soaked while he waited, standing to attention by the carriage door while the others fussed around. His only moments of warmth were with Biddy. She didn’t call him names but talked to him eye to eye like a friend or cousin. True, her eyes were horribly pale, but they did not, as he had once believed, have the power to penetrate his skull with dangerous spirits. And she laughed with him, teasing him when he talked about home.

‘In my country the rain is warm as tea,’ he confided, as they huddled beneath the overhang of a roof, waiting for their mistress.

‘You are having me on there, Mr Loveday. How can rain be warm?’

He told her how he would pick a tray-sized lontar leaf to carry above his head, to shelter from the tea-warm rain. She shook her head again.

‘I don’t know how you think it up, Mr Loveday. Sheltering under a leaf. You must think I were born yesterday.’

Mr

Loveday. He liked that. It made him feel for a moment like a solid man and not a fluttering ghost. Then she reached out and touched his arm. Leaning back against the dripping carriage Loveday’s eyes grew suddenly hot. It was the first time since passing to this strange world that any person had reached out to him in friendship. He could still feel Biddy’s fingers on his arm, and it warmed him more than a thousand fires. If only she knew him as he once had been; a hunter, a warrior, a man!

As the carriage shuddered and swung, the spirit that lived inside him, his

manger,

felt like a bird caught in a net. Commanding his limbs to balance on the narrow board, he released his spirit to go where it chose. Soon, somewhere else there was rain, pain, and misery – here in the limpid turquoise water the waves sucked and broke, with the rhythmic sound of the ocean’s heartbeat.

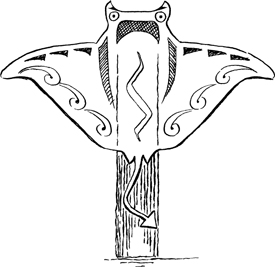

He was hunting with his clan; standing high on the harpoon platform, a warm rush of air refreshing his body each time the boat crested a wave. They were skimming just behind a vast

bělelā,

a black ripple-edged devil ray speeding beneath the water. Fear and excitement mixed in his veins. It was a monster, the length of three tall men, its wingspan even wider. It was an easy strike – he raised his right arm and drove the harpoon down deep into the creature’s back. The harpoon stuck firm and hard in the black shining flesh.

‘Stick another hook in. Quick, quick,’ he cried in triumph as he held the bucking rope. But from the corner of his eye he saw his younger brother, Surti, leap down from the platform onto the creature’s back, gaff in hand. Very fast, before he could form words of warning, the creature made its move. The vast

bělelā

raised its two great wings and wrapped them tightly around Surti’s body, knocking him flat and trapping him like an oyster in a shell. The boy gave a gasping scream, and Loveday watched as his terrified face was knocked flat against the creature’s night-black skin. Then, with a shudder of farewell, the

bělelā

tugged with all its might and vanished below the water.

Loveday looked about himself, amazed. The crew was crowding at his back, gaping at the white foam where the

bělelā

had plunged, carrying the boy wrapped inside its wings. Someone had to do something. The discarded rope at his feet was unravelling faster than a snake darting into the bush. Grasping a second harpoon, Loveday ran to the front of the platform and dived after the disappearing rope. In a gushing eruption of spray he found the harpoon line and grasped it tightly. It pulled him crazily down into the water, dragged by the monstrous

bělelā

that strained and plunged at the other end of the rope. Surely the harpoon will loosen, he thought. Yet it stuck firm. He was descending fast from the sun-warmed shallows to the frozen indigo deeps. I must die, he told himself, rather than lose my little brother. I will never let this rope go.

Yet he needed air. His chest rasped with pain and his head felt as fat as a watermelon. Time wore on, like a net stretched around a monstrous catch. The

bělelā

ducked and weaved, trying to escape the drag of the rope. A terrible darkness dimmed Loveday’s eyes. Then, like a child being born to the world, he felt sunlight warm his back. Air and sunlight burst noisily around him. He gasped and blinked, panting until the pain in his chest grew less. The rope was still tight in his hand. He looked about himself. Loveday could see the

bělelā

’s shape trembling beneath the swell; its wings moving freely. Where was Surti? He had disappeared. Drowned, surely drowned, answered the grim voice in his head. They had surfaced in the

bělelā

’s feeding ground, where the creature now grazed upon plankton. Some way behind them trailed the boat, a line of men huddling at the prow.

Honour blazed in his mind. He had to avenge Surti. Like a ravening shark he launched himself out of the water onto the head of the creature. It was the work of an instant to thrust his harpoon deep into the

bělelā

’s brain and kill it. He enjoyed a moment of hot satisfaction – he hated that creature, he wanted to beat it to soft pulp for taking the innocent boy.

Soon after, the crew arrived and lifted the beast up from the sucking ocean, carrying the

bělelā

into the airy world of men. Loveday watched as the men slit open its hollow bladder of a body and found nothing inside it but plankton. Why had the gods done this to him?

He felt weak and confused. The sun was setting and the waves were chopping fretfully. He looked out across the uneasy waters, haunted by the boy’s pale face.

‘We must go,’ his captain Koti said, and the words brought an anguished pain to Loveday’s being.

‘No,’ he insisted. ‘Wait.’ So they waited as the sun dipped into the sea in a red splash. He prayed, offering the father god, Bapa Fela, anything, any gift, any sacrifice. He had to find Surti alive. Otherwise, his happy life was over.

As if waking from a trance, he heard a commotion from behind him and a piping shout. The men were pulling something over the rail. Hope almost blinded him as he struggled through the huddling crew. Then, out of their centre staggered Surti, naked and shivering, his arm bleeding – but alive! Loveday ran to him and shook him by the shoulders. ‘You stupid boy,’ he said, ‘you are alive, but it is no thanks to your idiocy. Thanks only to the gods.’ And he embraced the boy and marvelled to feel the wriggling life inside his flesh.

After a sip of toddy, the boy told them that the

bělelā

had let go of him as soon as it made its descent. He had swum up towards the light, but in his giddiness had got tangled in the ropes. There he had hung, battered against the hull as the boat hurtled after its prey. ‘I called to you, but no one heard,’ he said.

‘You are wrong,’ said Koti, his wrinkled face very grave. ‘The gods heard you and witnessed your brother’s great courage. They have rewarded him with victory over the

bělelā

and over death itself.’

The

bělelā

’s dismembered body slid across the floor of the boat, trailing gore and slime. It was a monstrous size – it would feed the whole village. The boy was safe, and grinning as the older men cuffed him. Everyone wanted to touch Surti and his brother, to take for themselves a little magic from the boy who had survived the

bělelā

’s embrace and the man who had avenged it. Loveday stood firm at the prow, a man whom other men respected, and women admired.

That day the light of his Bapa, the sun, had shone inside his muscled chest. It had shone in his mind like a ball of fire. He had not known, then, that it would be his last victory. That soon the strange ship would arrive. That soon his courage would be smothered like a beacon in a storm.

* * *

Suddenly his body was tumbling through the air. He landed with a thump and found his mouth pressed hard into mud. What place was this? Rain, pain, and trouble returned. He looked about and found he was lying in the road, flung from the carriage into a rut of earth and stone. Dragging himself upright, he saw the carriage was tilting awkwardly, its back wheel hanging at a wounded angle. Could his troubles get any worse? Mr Pars and George were trying to calm the whinnying horses. Suddenly the carriage door opened and his mistress demanded to know what in the devil’s name was going on. Loveday peered into the gathering twilight and groaned.

Being Martinmas, November 1772

Biddy Leigh, her journal

An English Rabbit of Cheese

Toast your slices of bread then pour as much wine over as will soak in. Cut up a plate of cheese, very thin and lay it thick over the bread. Set it before the fire and brown the top with an iron shovel heated in the fire. Serve it away hot.