An Economy is Not a Society (5 page)

Read An Economy is Not a Society Online

Authors: Dennis; Glover

As Panda never forgets to remind us, the Labor Party made much of our success possible. Our old high school â Doveton High, long since flattened to make way for a housing estate â was given special âdisadvantaged schools' funding by Gough Whitlam and by Kim Beazley's father, Kim Beazley senior, and ours was the first cohort of students to benefit fully. Ours was the first in a number of years to be offered the Higher School Certificate â before then, the smarter kids transferred to other schools close by â and after us, the sixth form lasted for only a couple more years, with smaller enrolments and a narrower subject range before it ran out of puff. And when we got to TAFE and university they were free.

Education has taken us far, but the true context that made our upward mobility possible was a local economy that gave every family one or more jobs. Moderate affluence, not economic deregulation, is the magic ingredient that gave us our start, and it can do it for others. In the absence of that moderate affluence in a deregulated world, downward mobility is the result. Doveton used to create success stories like that. The question is: can it do so again?

I'm generally against statistics â you will note their comparative absence in this book â not because of what they tell us, which can sometimes be useful, but because they make it too easy to ignore what is going on in front of our very eyes. It's too tempting, isn't it, to sit in front of a screen in a warm office, look at lines of averages on graphs edging upwards and believe that, for everyone, life is getting better. The big-picture studies so beloved of the managerialists, like those by the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM), suggest that over the last decade and a half, every section of the population has got wealthier, even if some have got far wealthier than others.

According to NATSEM, the lowest 20 per cent of income earners have seen their standard of living increase by 27.1 per cent since 1985, and even welfare recipients are 11.9 per cent better off (although those who get their income largely from capital saw a rise of 64.8 per cent). It's abstractions and nationwide averages like this that make us complacent about what's really happening in the places we don't really want to know about. So what do the non-averaged statistics, the ones about places like Doveton, tell us?

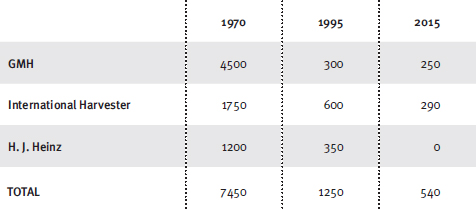

Doveton was created by the Victorian Housing Commission in 1955 with the specific goal of providing housing for employees of the Big Three factories of GMH, International Harvester and H. J. Heinz. By its completion in 1966, around 2500 homes had been built. There were certainly plenty of jobs for the families living in them. In 1970 those three factories alone employed the following numbers of people in permanent, full-time jobs: GHM 4500, Heinz 1200, and International Harvester 1750 â a total of 7450. By 1995, this had been reduced to GHM 300, Heinz 350, International Harvester (now the truck manufacturer IVECO) 600, for a total of 1250. In 2015 the totals are GMH (now HSPO) 250, Heinz 0, IVECO 290 â a total of 540. That's a net loss of 6910 permanent, full-time jobs.

Jobs at the Big Three, 1970â2015

To put it another way, in 1970 there were three jobs in these factories for every Doveton family; by 1995 there was one job for every two families; today there is just one job for every five families. Remember, this is for a community that was created with the specific purpose of housing employees for these three factories. If you take those jobs away but keep the houses there, and if you continue to fill them with the sorts of people who need low-skilled factory jobs, an interesting social experiment begins.

The net result? Consider this: in 1966 the unemployment rate in Doveton was less than 1 per cent (below the national average of just under 2 per cent), by 1991, at the height of the ârecession we had to have', it was 19 per cent (the national average then being around 10 per cent), and in 2015, after no fewer that twenty-three years of uninterrupted economic growth, it stands at 21.1 per cent (the national average being 6.1 per cent). Twenty years after the factories began closing down, the unemployment rate in Doveton is actually higher than during one of the most psychologically destructive recessions since the Great Depression.

During those dark recession years when the economic reform revolution reached its terrible apogee, my father, my mother, my youngest sister and her husband were all made redundant, meaning that four out of eight working adults in my family, all of whom were still living in suburbs adjoining Doveton, lost their jobs. (My brother-in-law, who back then was a unionised auto worker, has only once voted Labor since.) And this does not take into account the fact that the definition of âunemployment' has changed, making the comparison even worse. In recent years, other jobs have been created in the warehousing and small-scale manufacturing hinterland to the suburb's south, but clearly these jobs have not gone to the people of my old suburb. For places like Doveton, the recovery has been a largely jobless one. That is the problem.

The effect of this on the material quality of life of Doveton's residents has been dramatic. In 1966, 10 per cent were in the lowest income category, by 1991 that had risen to 37 per cent, and in the 2011 Census 34.9 per cent of residents were still classed as âlow-income households' â which means they earned less than $600 per week, or roughly the minimum wage of one working parent. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics' standard measure of advantage and disadvantage â Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas, or SEIFA â Doveton is now the fourth-most disadvantaged suburb in Victoria.

Perhaps the saddest thing to contemplate is that there are many Dovetons â many once affluent public housing suburbs that were built to support thriving industries, but that have been left behind by the revolution. Doveton itself is probably not even the poorest of them. In Dandenong, immediately next door to Doveton, unemployment is 21.7 per cent. Norlane, a Victorian Housing Commission estate built around the Ford factory in Geelong, has an unemployment rate of 20.7 per cent. Broadmeadows, in Melbourne's north, another Victorian Housing Commission site, which is highly dependent on the Ford factory in nearby Campbellfield, has an unemployment rate of 25.7 per cent. Elizabeth, in Adelaide's north, is a South Australian Housing Trust site, developed in large part for workers in the nearby Holden factory, and it now has a frightening unemployment rate of 32.6 per cent. Remember, all these car factories will be gone before the end of 2017, when all Australian car manufacturing will cease, and their unemployment rates, which are already as high as or higher than Doveton's, will be far higher still. These places are potentially heading towards a social catastrophe.

What we have done in places like Doveton is create a new economic class. It's true that, for many working-class people, the changes of the past thirty years have been liberating. We've coined a name for these people â âaspirationals' â and their success is something to celebrate. Much has been written about this aspirational class, which has many fair-weather champions, so I won't detail its considerable success here, except to say that there are suburbs full of people like this not far from Doveton, and obviously many individual examples in Doveton itself. But while we lavish attention on the aspirationals' success, we've turned our backs on their former workmates and neighbours who didn't succeed when the economy was pulled out from under them. We didn't do enough to help them succeed, but we should have.

So who are they? I don't like the term âunderclass', with its condescending connotations of depravity and crime, and its assumption that the victims are themselves to blame for their misfortune. This is not a law-and-order issue but an economic and social issue. âHousos' is another insulting and degrading epithet â and anyway, this isn't about housing, it's about people. Above all, this is an employment issue. So let's call this class what it really is: the ânon-working class', or perhaps more accurately the âonce-working class'. Our economic revolution has created it, and we collectively bear a moral responsibility to remove the ânon' and the âonce' from its names.

The economic reformers led us to believe â in fact,

promised

would probably not be too strong a word â that greater productivity, by leading to higher economic growth, would make the existence of this sort of class unlikely: that all boats would float as the tide rose and everyone could aspire to something better. Even they couldn't have dreamed that their high tide would last for twenty-three years. But here it is: Australia rich, Doveton and other places like it poor.

A wise person might consider the possibility that the two results might be linked, and that the

way

we have pursued growth has prevented many people in places like Doveton from sharing in the rewards. In the past, people in these places were shielded from the full winds of the market to help us create a fairer and better society, but now the shield has been ripped away and such places have been exposed to a hurricane. This is more than just a quantitative change in our economy â it is a new economy without a heart or conscience. We used to create wealth by including places like Doveton; now we create wealth by excluding them. And in doing so, could it be that we've changed our economy in some fundamental way, without fully realising the import of what we are doing, removing not just the goal of equality from our calculations but removing moral considerations more generally? And could it be that in doing so, we've changed ourselves as a people? This is what the aggregated national statistics don't tell us.

Doveton is the suburb that was murdered. And it is not alone. Its continuing existence is an embarrassment to the economic reformers because it proves that their theories were either wrong or heartless. When the suburb's factories shut, Doveton suffered a mini depression that, like a runaway steamroller, smashed everything in its path. That steamroller is still on the loose across the land. Other places got the creation, but Doveton and places like it got the destruction. Twenty years on, little has changed, as I was to see.

CHAPTER 3

GROUND ZERO

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place?

â H

ORACE

S

MITH

T

he word

trespass

has far more ethical meaning than it deserves. Simply by erecting a sign saying âDo Not Enter', the state or the corporation puts into your mind the idea of transgression. Go through that broken gate, squeeze your way through that gap in the builder's fence, stride confidently past a momentarily empty security office and you become a sort of moral outlaw. But a âDo Not Enter' sign might also alert you to something someone else doesn't want you to know about.

The Endeavour Hills Secondary College was once called Doveton North Technical School. It opened in 1969 to train boys to do the jobs of their fathers by preparing them for apprenticeships â or at least for the discipline of the time clock â at the Big Three. My friend Dave, with whom I used to open the batting, went here. Today, it's the sort of place the economic reformers don't want you to see. Here is the epicentre of creative destruction, the Ground Zero of Professor Schumpeter's dark vision.

The first thing you notice as you enter the school today â which you do by bending double to pass though a hole smashed in one of its doors â is the unnerving crunch of broken glass under your feet. In retrospect, it shouldn't come as much of a surprise, since the desolate playground is littered with unwanted mattresses, paint tins and other hard-to-dispose-of rubbish. Still, nothing can prepare you for what's to come, especially when you think to yourself that this is Australia, not some American city like Detroit where people don't really count.

In the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan was deploying cruise missiles on the borders of the Soviet Union, a new genre of movie appeared, set in the nuclear Armageddon. You might remember some examples:

Threads, The Day After, When the Wind Blows.

The most disturbing thing about these movies wasn't the physical destruction they showed but their belief that a post-nuclear society would descend into some sort of chaotic lunacy, a kingdom of the insane brought under control by a modern version of feudalism, ruled by street gangs.

Perhaps because I was fascinated by these films (a fascination which started when a teacher at Doveton High showed us Peter Watkins' then shocking mock documentary,

The War Game),

the first word that comes to my mind as I enter the school building and stare down the main corridor is

apocalypse.

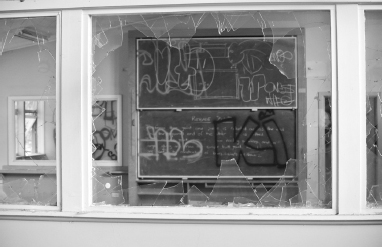

Down all four corridors of the main block â which consists of three parallel chambers about fifty metres long, connected mid-section by a shorter fourth one â every wall has been defaced by the warnings of street gangs, and literally every panel of glass smashed. Between elaborately painted tags, there are the usual obscenities and crude symbols of people being hung by the neck. In almost every classroom the walls have been roughly removed, as if some army of psychopathic home renovators had set to them with long-handled hammers. Here and there floorboards have been ripped up, the better to get to the copper wires and the recently installed fibre-optic cabling. In one of the central courtyards, a large, twisted pile of coloured tubing of various diameters is evidence of the building's nocturnal disembowelling; perhaps there's money in it.

Particular attention has been paid to the entrance hall, which looks like a high-street bank frontage that has been ram-raided by a truck. Next to it is a large yellow arrow, possibly put there to manage the traffic when the place was still alive with the shouts and movement of teenagers. Over the arrow, some illegal visitor â who knows, perhaps a grammatically challenged former student, now unemployed â has spray-painted the words âIF U WANT 2 DIE, THIS WAY, FUCKERS!' (I've added the commas to make the meaning clear.) It's not as pleasant as the slogans about flagstones and beaches the Parisian students wrote on the walls of the Sorbonne in 1968 but it's rather more direct. In one classroom, the day's lesson â on how to make a rebate joint, a skill that could help some youngster get a job in the building trade â is still in chalk on the blackboard.

The entrance hall â after the apocalypse â¦

A classroom â newly renovated â¦

A slogan for Professor Schumpeter â¦

Lessons for us all â¦

Perhaps the strangest thing about the insides of the now destroyed school is the feeling of newness. Between the holes and the graffiti and under the broken glass and cables, everything is in nearly mint condition. There appears to have been a very recent and major fit-out, leaving behind new classroom partitions, pristine whiteboards, rows of shattered toilets that are still sparkling white, walls yet to be turned grubby by the rubbing of teenage shoulders, and carpet not yet muddied by dirty shoes. It's as if the whole place was scrubbed clean for its execution, like a sacrificial infant at the temple of a Mayan sun god.

Disembowelment â¦

The insides of this dying building are so breathtaking that they induce in me a variety of blood-pumping excitement; after all, it's not impossible, and perhaps even not unlikely, that some ice-crazed adolescent might appear around a corner at any moment with a knife. It's only when I crawl outside again that my sense of melancholy returns. There, in front of me, is an old soccer field, the grandstand burnt down and razed by council bulldozers as a safety precaution, the pitch alternately bare and weedy. Behind the main building is the vocational education block, similarly smashed and defaced. They once taught young people skills for the auto trades here; now, having decided to leave car manufacturing jobs to the Germans, French, English, Koreans, Thais and Chinese, we can safely leave public assets like this in ruins. At least the economists will be happy, because the otherwise unused land is now being put to the most efficient use their collective wisdom has been able to devise: as a junkyard.

As I walk away from the school, scale its fence and look back, I notice that it is slowly being overtaken by nature. Weeds sprout from every garden bed, concrete crack and gutter like those reclaiming the Roman forum in the famous etchings by Piranesi. Parts of the roof are disappearing; whether blown off or stolen it's hard to tell. Soon the rain will be getting in, the walls will be getting damp and the place will be unsafe to enter. If you've ever read John Wyndham's classic novel

The Day of the Triffids,

you'll know that its best scene is the one where the protagonist travels back to London years after the apocalypse, only to find it reclaimed by nature, its pavements choked by spreading weeds, turf growing on roofs, tree roots undermining buildings and branches poking through smashed windows. That's Doveton North Tech today, once proud but now an abandoned ruin, slowly disappearing beneath nature's onslaughts.

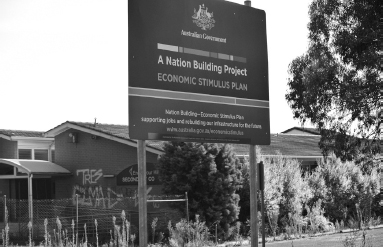

There is, however, one surface in the complex that remains untouched by the hands of the vandals. It is the sign boasting that the now completely wrecked and abandoned school received money from the stimulus plan that followed the global financial crisis. âNation Building â Economic Stimulus Plan,' it reads, in the sort of dubious English that the managerialists who devised the plan love so much, âsupporting jobs and rebuilding our infrastructure for the future.' It seems the school had been given a major renovation and refit just before it was closed.

A nation-building project â¦

Here is the Building the Education Revolution plan at work. Its inspiration, John Maynard Keynes, once said that in a recession the most rational thing to do is pay people to bury sacks full of pound notes in disused mineshafts, and then pay the same people to dig them up again. This could have been the sort of thing he meant. Having read that morning in the

Financial Review

that the market for collateralised debt obligations is once again booming, I muse that perhaps when the next financial crisis comes we can dig up the buried foundations of this school as yet another Keynesian make-work project.

While I'm taking photographs of the sign, a Vietnamese-Australian couple pull up in their car, taking me (again in my fluoro vest and hardhat) for a council employee. When is the council going to sell the site, they ask, because they want to buy the land and build apartments on it. I tell them I have no idea, but that some of my friends went to school here and it's still owned by the Department of Education, and everyone knows they move at a snail's pace. Might be years! They leave disappointed.