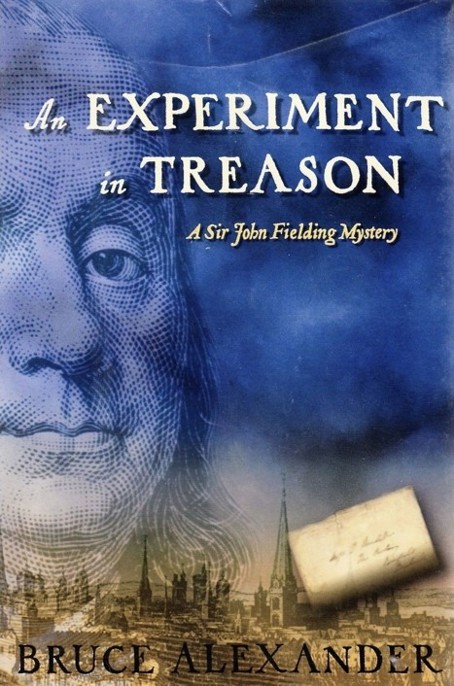

An Experiment in Treason (35 page)

Read An Experiment in Treason Online

Authors: Bruce Alexander

“It is from Mr. Bilbo, sir.”

“Well, read it, will you?”

“Certainly! He begins, ‘Sir John — ’”

“Just so?”

Yet I was already reading the rest aloud:

Though this letter will be short, it has taken me a terrible long time to write. I threw away just so many as I started, which was quite a few. I’m writing to ask your forgiveness for breaking my word to you, which I know I did. It was that or hand over the woman I love, which I would not do and still would not do today. When I say I’m asking you to forgive, I mean man to man, friend to friend, for I know there’s nothing can be done for me legally. And so I’ll have to stay away from England. We are not likely ever to meet again in this life. It’s just I would sleep better at night knowing all was straight between us. It’s a sad thing, but I’m certain, and each day more certain, that there will be a war coming soon between England and America, and I know we’ll be on different sides, we will, sure. There’s naught can be done about that, just that those things are now all beyond us. The lad Bunkins says he thinks often of you and Jeremy and would like to be remembered to you both. He’ll never forget you, and I will not either. You accepted me for just what I was. May God bless you for that.

Having read through the body of the letter, I paused, and then added, “As I said. Sir John, it is signed ‘John Bilbo. ‘

“That is all, then, Jeremy?”

“That is all, sir.” Then did I ask: “Do you think he is right? — About the war, I mean.”

“I fear that indeed he may be,” said Sir John.

Though I am usually quite respectful of the facts of history, I admit to having taken a number of liberties in An Experiment in Treason. Students of American history will recognize the foundation of the story as the Affair of the Hutchinson Letters, an important milestone on the road to Bunker Hill. Because this is a work of fiction, it was necessary to fabricate murders, to cut certain corners and move a few dates forward or back; this was done, for the most part, to introduce Sir John Fielding into the plot.

Yet the facts that support the fiction are fascinating in themselves. The letters were indeed stolen — though even to this day the identity of the thief is unknown. What is known, however, is that Benjamin Franklin played an important role in getting the letters to certain members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. That much he admitted in an article written by him that appeared in the London Chronicle and was quoted in its entirety in my text. Whether or not he did more is anybody’s guess. Yet for that much he was punished in the Cockpit in the manner I have described.

All this and more I derived from various books that I had on hand:

The First American: the Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin, by H. W Brands, New York, 2000.

The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, by Don Cook, New York, 1995.

A Struggle for Power: The American Revolution, by Theodore Draper, New York, 1996.

Origins of the American Revolution, by John C. Miller, Boston, 1943.

Perhaps most beneficial of all to me was the Library of America’s selection of Writings by Benjamin Franklin himself.