An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality (37 page)

Read An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality Online

Authors: William Stoddart,Joseph A. Fitzgerald

Tags: #Philosophy

The Question of Reincarnation

125

Some of those who have failed to understand the doctrine of

anātmā

(see pp. 43-46) have gone so far as to allege that Buddhism

denies the existence of the soul. In point of fact, Buddhism takes enor-

mous pains to emphasize “karmic continuity” or, in the words of Frit-

hjof Schuon, “the moral causality of that living and conscious nucleus

that is the [human] ego”.2 The numerous references in the Buddhist

Scriptures to posthumous hel s (the fate awaiting those who have

squandered the precious gift of human life) cannot be lightly brushed

aside.

*

* *

The term “reincarnation” is sometimes used to describe the mecha-

nism of Tibetan lamaist succession, for example, that of the Dalai La-

mas. This is rather misleading, however, as in this case, it is the “office”

or “function” (and not the individual) that is “reincarnated”. It would

be more accurate to say that the office or function is “bequeathed”,

“transmitted”, or “passed on” to a traditional y chosen successor.

A twentieth-century Dalai Lama might well say: “As I said in

1600. . .”. Here it is the office or function that is speaking. A Pope often

says something like: “As my august predecessor said in 1600. . .”. In

Tibetan terms, he could just as well say: “As I said in 1600. . .”. In such

cases it is the office or function that is involved.

The perfume of flowers goes not against the wind, not even the

perfume of sandalwood, rose-bay, or jasmine; but the perfume

of virtue travels against the wind and reaches unto the ends of

the earth.

Dhammapada, 54

2 Frithjof Schuon,

Treasures of Buddhism

, p. 37.

126

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

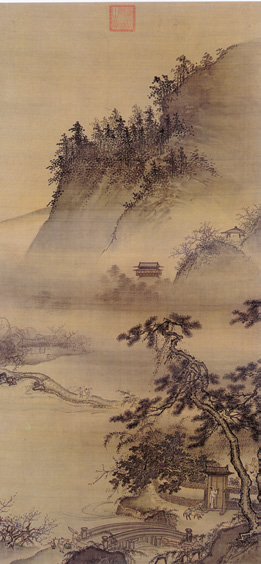

Tai Chi,

Returning Late from a Spring Outing

, China, 15th century

At the horrible time of the end, men will be malevolent, false,

evil, and obtuse and they will imagine that they have reached

perfection when it will be nothing of the sort.

Saddharma-Pundarīka-Sūtra

127

(22) The Question of “Pantheism”

Very often the term “pantheism” is applied to Oriental doctrines, espe-

cial y the metaphysical and/or mystical doctrines of Buddhism (both

Hīnayāna

and

Mahāyāna

),

Vedānta, Taoism, and Sufism. The immedi-

ate and formal answer to this is that no traditional doctrine is panthe-

istic, since the vague, superficial, and contradictory notion of panthe-

ism (a material or substantial identity between two different levels of

reality) is a purely modern phenomenon.

What rescues all traditional doctrine, including Buddhist, from

the charge of pantheism is, in a word, transcendence: Ultimate Real-

ity is transcendent, and there is no material or substantial identity be-

tween Ultimate Reality and the manifested world (or between Creator

and creation, as the “theistic” religions would say). This applies also in

the case of Hindu and Greek “emanationism”, in which the Principle

remains whol y transcendent of any of its manifestations.

Of course all metaphysical or mystical doctrines (be they Oriental,

Greek, or Christian) are doctrines of union. The metaphysicians and

mystics of the great religions have referred to different degrees of union,

notably ontological or supra-ontological, that is to say, relating either to

the level of “Being” or “Beyond-Being”. (See pp. 48, 50-51.) Christ said:

“I and the Father are one”, and the Christian way is essential y to unite

oneself with Christ. In Hinduism, it is said that “all things are

Ātmā

”.

This means (and it is in accordance with the doctrine of Plato) that al

things have their principle on a level of reality

above

the one on which

they “exist”, and that the Principle of principles is

Ātmā

.

There is indeed

“essential” identity, but there is “substantial” discontinuity.

In Hinduism it is also said: “The world is false,

Brahma

is true”,

while in Christianity it is said: “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but

My words will not pass away.” To al ude to the ephemerality of all cre-

ated things (something that has been known from time immemorial)

is not pantheism, but simply true doctrine.

It is true that there are mystical and scriptural expressions (both

Oriental and Christian) which use figures of material continuity, for

example, when it is said that all creatures are vessels made from the

same Clay, or that all rivers return to the one Ocean; or again, when

Christ says: “I am the vine, ye are the branches.” However, the symbolic

nature of such utterances is perfectly clear, and in any case the tradi-

tional commentaries ensure that the principle of transcendence is ful y

safeguarded.

128

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism

The idea of a material or substantial identity between two differ-

ent levels of reality (or the obtuseness of taking literal y any metaphor

which might seem to suggest this) devolves on European philosophers

and poets of recent centuries. The idea is far from reality and devoid of

meaning; it is foreign to Buddhism and all other traditional perspec-

tives.

Torii

at Itsukushima Shrine, Miyajima, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan

People find themselves drowning in a sea of accidents; they do

not know how to reach the one substance which alone is truth.

Chiang Chih-chi

129

(23) Shinto: Buddhism’s Partner in Japan

“The Way of the Gods” (Kami-no-Michi)

As mentioned on pp. 54 and 101, certain indigenous traditions (de-

rivatives of Hyperborean shamanism) co-exist with Buddhism in some