Another Insane Devotion (21 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

Bitey also went missing in September, late in the month, and I was terrified that she'd been snatched by a backwoods Satanist who was going to sacrifice her for Halloween. I don't know if we had real Satanists where we lived, but we had surly, thick-witted teenagers in Slipknot T-shirts who'd tell themselves they were Satanists as a pretext for setting an innocent house cat on fire, the same way earlier generations of surly thick-wits had told themselves they were Christians. How many miles I rode my bike in search of her, summoning her with the racket of IAMS “Adult Original with Chicken.” “Bitey!” I called over and over. How many times in years to come F. and I would go about crying cats' names in loud, forlorn voices. People pretended not to stare at us from their porches, and we pretended not to see them staring.

A few weeks after we got her back, Bitey developed a sudden, terrible thirst. All night long she lapped from her bowl, frenetic and pop-eyed, then stumbled away like a drunk. When I took her to the vet the next morning, he thought it was diabetes. In the course of the day, the diagnosis kept changing. She had diabetes, but somehow it involved her liver. Then it wasn't diabetes. It might be cancer, but an X-ray showed no tumors. That evening F. and I came to see her and found her lying on her side on a steel table, emaciatedâit had only been a day!âher eyes glazed. It was the first time I ever cried in front of F. She

held me. Once I'd imagined that having someone to hold you when you were sad would be one of the benefits of marriage. But in the moment, it only felt embarrassing, and it didn't take away the fact that my cat was dying.

held me. Once I'd imagined that having someone to hold you when you were sad would be one of the benefits of marriage. But in the moment, it only felt embarrassing, and it didn't take away the fact that my cat was dying.

Actually, she wasn't dying, but it would be another week and $3,000 before I knew that. No one could ever say definitively what she'd had, what she

still

had when she came home with us, only that treating it involved feedings of a revolting prescription cat food that had to be blended with water into a grayish-brown slurry and then squirted into Bitey's mouth with a syringe, plus daily doses of a feline-strength formulary of the enzyme SAME, popular in Europe as an antidepressant, and daily administrations of subcutaneous fluids and antibiotics. The treatment was supposed to take a couple months. F. was away on a job, and I worried that I wouldn't be able to do it all myself. But Bitey was still weak and docile. All I had to do was sit down beside her on the bed, pet her a little to get her in the mood, then reach for the bag of fluid I'd hung from a ceiling hook, put a clean point on the line, and slip the point into the loose skin at her scruff. The worst part was the little pop of the incoming needle. I think it was that, rather than pain (cats don't have a lot of nerves back there), that sometimes made her start. For the next five minutes, I'd sit with her, scratching her ears as I watched a hundred milliliters of fluid drip from the bag and travel under her skin in a mouse-sized bulge before it was absorbed. About halfway through the procedure, I'd inject the antibiotic into a Y-port in the line. How astonishing that a doctorâeven an animal doctorâhad sold me a box of twenty-gauge syringes and that I was using those syringes on my cat and not myself. Bitey took it stoically. Only toward the

end would she start growling. “Almost done,” I'd tell her and give her a treat to keep her quiet a while longer.

still

had when she came home with us, only that treating it involved feedings of a revolting prescription cat food that had to be blended with water into a grayish-brown slurry and then squirted into Bitey's mouth with a syringe, plus daily doses of a feline-strength formulary of the enzyme SAME, popular in Europe as an antidepressant, and daily administrations of subcutaneous fluids and antibiotics. The treatment was supposed to take a couple months. F. was away on a job, and I worried that I wouldn't be able to do it all myself. But Bitey was still weak and docile. All I had to do was sit down beside her on the bed, pet her a little to get her in the mood, then reach for the bag of fluid I'd hung from a ceiling hook, put a clean point on the line, and slip the point into the loose skin at her scruff. The worst part was the little pop of the incoming needle. I think it was that, rather than pain (cats don't have a lot of nerves back there), that sometimes made her start. For the next five minutes, I'd sit with her, scratching her ears as I watched a hundred milliliters of fluid drip from the bag and travel under her skin in a mouse-sized bulge before it was absorbed. About halfway through the procedure, I'd inject the antibiotic into a Y-port in the line. How astonishing that a doctorâeven an animal doctorâhad sold me a box of twenty-gauge syringes and that I was using those syringes on my cat and not myself. Bitey took it stoically. Only toward the

end would she start growling. “Almost done,” I'd tell her and give her a treat to keep her quiet a while longer.

Did she understand that this was for her own good? As long as we're talking about the threshold between human and animal, we might consider that humans are the only beings that seem to recognize that some kinds of painful and degrading treatmentâinjections, catheterizations, Hickman lines, CAT scans and MRIs, the shaving of head and pubic hair, enemas, colonoscopies, the splitting of thorax or abdomen and the plucking out of internal organs, which sometimes

are not put back

âthat these ordeals, which any sentient creature might be expected to fly from howling, are beneficial to them. That the stickers and splitters have friendly intentions.

are not put back

âthat these ordeals, which any sentient creature might be expected to fly from howling, are beneficial to them. That the stickers and splitters have friendly intentions.

Â

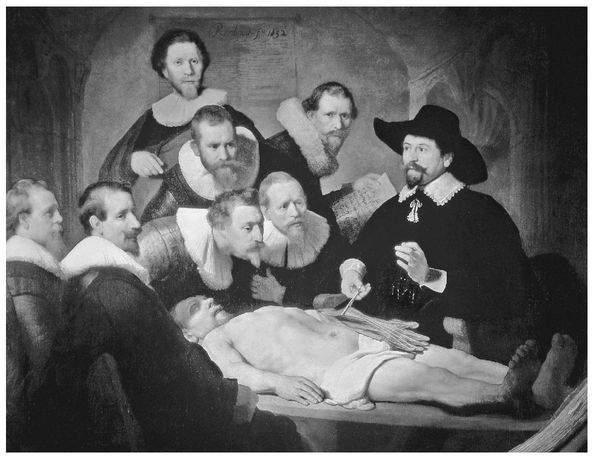

Rembrandt van Rijn,

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

(1632), Mauritshuis Museum, Amsterdam. Courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

(1632), Mauritshuis Museum, Amsterdam. Courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library.

Children have to be taught this; it can take years. And even grown-ups sometimes forget. A friend of mine, coming to after a surgical procedure, began clawing at the lines in his hands, wanting to know why he was being tortured. Later he said he must have gone out of his mind for a while. But you might as well say he'd momentarily come into his right one. In his delirium, he'd broken free of the decades of indoctrination that teach us to accept pain and humiliation as long as they're inflicted by strangers in lab coats.

F.'s father had also broken free of his indoctrination; I don't know that it did him any good. He hadn't been to a doctor since one had diagnosed him with chronic leukemia years before. He didn't speak of people going to the hospital; he spoke of them going to the slaughterhouse. “The bastards tell you they're taking you to the slaughterhouse for

some tests

, and that's the last anybody hears of you.”

some tests

, and that's the last anybody hears of you.”

We visited him the Christmas before we were married. He and F.'s mother had divorced late, and he still hadn't gotten over it. The dark condo with its brown carpeting unraveling like a laddered stocking. The yellowing cards of Christmases past arrayed on shelves and coffee table. The cheap cookware that had never held anything but canned soup. They were the marks of someone who either couldn't live by himself or had chosen not to, preferring to stage the last years of his life as a reproach: to his faithless wife, to the children who didn't visit him enough, to an entire world that knew nothing of his grief. The resemblance between father and daughter was eerie, down to the domed forehead and rabbit-like twitch of the nose. F. had done her best to create a festive atmosphere. She'd gone

to the shopping center and come back with a spiral-cut ham whose slices fanned open like the pages of a book. “Isn't it nice, Daddy?” She presented him with a heaped plate that he barely glanced at. “I suppose.” He said the ham wasn't as good as it used to be.

to the shopping center and come back with a spiral-cut ham whose slices fanned open like the pages of a book. “Isn't it nice, Daddy?” She presented him with a heaped plate that he barely glanced at. “I suppose.” He said the ham wasn't as good as it used to be.

In former years, F.'s father had been prone to rages in which he'd rail at his wife and shove the children around. The threats he'd made sounded preposterous to me, but they must have been frightening and deeply embarrassing to three naive adolescent girls staring mutely as a red-faced grown-up told them that Castro was going to march in and shove his cigar up their asses. Now there was no trace of the old ferocity. His voice never rose above a murmur. Still, as we were talking in the kitchen, the refrigerator let out a squeal, probably something wrong with the fan, and abruptly the old man bared his teethâbared them like an animalâand slammed it with the flat of his hand. “Bastard!” His eyes met mine for a moment, then looked away.

A few months after this, he fell ill. Probably he had been ill all that time but had refused to admit it. He couldn't eat, and he hurt everywhere. F. went down to Lexington to help care for him but, after a week, felt she had to go back to work. No sooner had her plane landed than she was suddenly struck by the certainty he was about to die. In a panic, she flew back once more and got there in time to sit by his bedside with her sisters as the last bit of life was twisted out of him.

During the time F.'s father was dying, I was sometimes petty with her. She was away, and I wanted her with me. She was sad and withdrawn, and I wanted her to be cheerful. Even now the memory of my behavior shames me. It also puzzles

me. My mother had died only five years earlier, and for a long time afterward I'd walked through the world in a dream and bristled at any claim other people made on my attention; you'd think I would have understood what F. was going through. I've been told this amnesia isn't unique, and I can only relate it to the amnesia that comes over women after they give birth. The only way to bear this thing is to forget it. Of course, a woman who's had children can always choose not to have any more. But when it comes to death, you can't push away your plate and say, “No thanks, I couldn't eat another bite.” The death kitchen goes on serving.

me. My mother had died only five years earlier, and for a long time afterward I'd walked through the world in a dream and bristled at any claim other people made on my attention; you'd think I would have understood what F. was going through. I've been told this amnesia isn't unique, and I can only relate it to the amnesia that comes over women after they give birth. The only way to bear this thing is to forget it. Of course, a woman who's had children can always choose not to have any more. But when it comes to death, you can't push away your plate and say, “No thanks, I couldn't eat another bite.” The death kitchen goes on serving.

We put off our wedding six months. Late that spring we went back to Kentucky to clean out the old man's house. Before we left, we held a small memorial. I don't remember if F. bought another ham; it would have been fitting. But there was nice food, and wine and flowers, and we covered the dingy furniture with sheets, which produced an effect that was both austere and ethereal. Not many people came, apart from the family. At the climax of the afternoon, F. put on a tape we'd made of music he'd liked: a cut of a Scots marching band whose shrilling pipes lifted the hair on the back of your neck; the theme song of the old TV show

The Avengers

; some big band jazz he would have listened to as a young man on a last leave before shipping out for Italy, where most of his unit was wiped out at Anzio. From that same period, there was “I'll Be Seeing You,” sung by Jo Stafford. Stafford's version may be the saddest song in the American songbook, saturated with yearning, slow as a dirge. Why does she sing it so slowly, you wonder? But, of course, “I'll Be Seeing You” is a song of the war

years, and it's clear that Stafford is singing to a man who won't be coming back. She knows it, and he knows it. She's singing a love song for the dead. This accounts for the omnipresence of its object. The singer sees him everywhereâthe children's carousel, the chestnut tree, the wishing well

.

Nothing like that happens when you just break up with somebody. In your imagination, she is where you know her to be: going out with an asshole she met at El Teddy's. Only the dead can be everywhere, and that's because they are nowhere.

The Avengers

; some big band jazz he would have listened to as a young man on a last leave before shipping out for Italy, where most of his unit was wiped out at Anzio. From that same period, there was “I'll Be Seeing You,” sung by Jo Stafford. Stafford's version may be the saddest song in the American songbook, saturated with yearning, slow as a dirge. Why does she sing it so slowly, you wonder? But, of course, “I'll Be Seeing You” is a song of the war

years, and it's clear that Stafford is singing to a man who won't be coming back. She knows it, and he knows it. She's singing a love song for the dead. This accounts for the omnipresence of its object. The singer sees him everywhereâthe children's carousel, the chestnut tree, the wishing well

.

Nothing like that happens when you just break up with somebody. In your imagination, she is where you know her to be: going out with an asshole she met at El Teddy's. Only the dead can be everywhere, and that's because they are nowhere.

I made the tape hastily, without EQ, so some tracks were much louder than others. Somehow I managed to lose several seconds of “Nessun Dorma.” I hate to think what F.'s father would have said about that, but none of the guests seemed to really notice. F. and I may have been the only people there who were listening to the music as music rather than as the background for a gathering that couldn't decide whether it was sacred or social. F. said that her father would also have listened to the music as music and gotten angry with anyone who tried to talk over it. His remarks would have been restricted to a running commentary on the soundtrack: “âNessun Dorma.' âNo one shall sleep.' From Puccini's immortal

Turandot.

” But over time the commentary would have become increasingly emotional, until he was pacing the living room in agitation and, eventually, in rage.

Turandot.

” But over time the commentary would have become increasingly emotional, until he was pacing the living room in agitation and, eventually, in rage.

The guests stole out until it was just F., her sisters, and me. The tape continued to play. The final track was a song F.'s father was unlikely to have listened to, Iggy Pop's snarling cover of “Real Wild Child.” But F. had asked me to put it on the tape, feeling it expressed some aspect of his personality. Maybe

it was the part of him that had bared his teeth in the kitchen, though I would have said that was just a passing convulsion of rage. You could imagine Iggy baring his teeth as he sang, but baring them the way you do when you're biting into a steak, a nice, thick, bloody one, the blood running down his chin. F. got up to dance, and I joined her. She's a terrific dancer, lithe and sexy and peppy and funny. One moment she'd be rolling her hips like a girl in a cage and the next she'd be prancing about on tiptoe, and she inspired me to be almost as uninhibited. It didn't occur to me that it might be inappropriate to dance at a memorial, especially the memorial of someone who, if he'd lived a few months longer, would have been my father-in-law. In former times, the Nyakyusa or Ngombe people of Tanzania were said to do this as a matter of practice, and their funerals, according to the anthropologist Monica Wilson, were correspondingly jolly:

it was the part of him that had bared his teeth in the kitchen, though I would have said that was just a passing convulsion of rage. You could imagine Iggy baring his teeth as he sang, but baring them the way you do when you're biting into a steak, a nice, thick, bloody one, the blood running down his chin. F. got up to dance, and I joined her. She's a terrific dancer, lithe and sexy and peppy and funny. One moment she'd be rolling her hips like a girl in a cage and the next she'd be prancing about on tiptoe, and she inspired me to be almost as uninhibited. It didn't occur to me that it might be inappropriate to dance at a memorial, especially the memorial of someone who, if he'd lived a few months longer, would have been my father-in-law. In former times, the Nyakyusa or Ngombe people of Tanzania were said to do this as a matter of practice, and their funerals, according to the anthropologist Monica Wilson, were correspondingly jolly:

Dancing is led by young men dressed in special costumes of ankle bells and cloth skirts, often holding spears and leaping wildly about. Women do not dance, but some young women move about among the dancing youths, calling the war cry and swinging their hips in a rhythmic fashion. . . . The noise and excitement grow and there are no signs of grief. Yet when Wilson asked the onlookers to explain the scene, they always replied, “They are mourning the dead.”

Turandot

is Puccini's last opera. He died before he could finish it, and it was given its present ending by a second composer.

When the opera was first performed at La Scala, on April 25, 1926, the orchestra fell silent in the middle of the third act, and the conductor Arturo Toscanini is said to have laid down his baton and addressed the audience: “Qui finisce l'opera las-ciata incompiuta dal Maestro, perchè a questo punto il Maestro è morte” (“Here ends the opera left incomplete by the Maestro, because at this point the Maestro died”). The curtain fell.

is Puccini's last opera. He died before he could finish it, and it was given its present ending by a second composer.

When the opera was first performed at La Scala, on April 25, 1926, the orchestra fell silent in the middle of the third act, and the conductor Arturo Toscanini is said to have laid down his baton and addressed the audience: “Qui finisce l'opera las-ciata incompiuta dal Maestro, perchè a questo punto il Maestro è morte” (“Here ends the opera left incomplete by the Maestro, because at this point the Maestro died”). The curtain fell.

Â

F. and I almost postponed our wedding a second time, since a few days before it was supposed to take place a pair of hijacked jetliners crashed into the World Trade Center. After a day or two of indecisionâduring which we fretted about how petty it was to even be thinking about a wedding when almost 3,000 of our neighbors had just been murdered before our eyesâwe were persuaded to go ahead: our friends who lived in the city said they

needed

us to go ahead. As one of them put it, “I need a party to go to.” If I'd had any real doubts, I might have been swayed by the stories of the people who jumped from the burning towers holding hands. I don't know if any of them were married to each other; some of them may have been lovers, as often happens in workplaces. For months and years, they'd kept their relation secret, but in a matter of minutes the need for secrecy was over, and they jumped together, in full view of the world, holding hands. A man and a woman leaping off a burning building while holding hands struck me as a metaphor for marriage, the clause in the vow that goes “till death shall us part.” But this probably says something about my laziness and the shortness of my attention span. It took only ten seconds for the people who jumped from the World

Trade Center to hit the ground, and that's not a long time to hold hands.

needed

us to go ahead. As one of them put it, “I need a party to go to.” If I'd had any real doubts, I might have been swayed by the stories of the people who jumped from the burning towers holding hands. I don't know if any of them were married to each other; some of them may have been lovers, as often happens in workplaces. For months and years, they'd kept their relation secret, but in a matter of minutes the need for secrecy was over, and they jumped together, in full view of the world, holding hands. A man and a woman leaping off a burning building while holding hands struck me as a metaphor for marriage, the clause in the vow that goes “till death shall us part.” But this probably says something about my laziness and the shortness of my attention span. It took only ten seconds for the people who jumped from the World

Trade Center to hit the ground, and that's not a long time to hold hands.

Other books

Grumble Monkey and the Department Store Elf by B.G. Thomas

Bitter Inheritance by Ann Cliff

Lasher by Anne Rice

Bristol House by Beverly Swerling

Strangers in Paradise by Heather Graham

Buccaneer by Tim Severin

Sheikh's Scandalous Mistress by Jessica Brooke, Ella Brooke

My Protector (Bewitched and Bewildered Book 2) by Alanea Alder

HUNTER by Blanc, Cordelia