Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (70 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

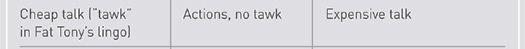

Under such epistemic limitations, skin in the game is the only true mitigator of fragility. Hammurabi’s code provided a simple solution—close to thirty-seven hundred years ago. This solution has been increasingly abandoned in modern times, as we have developed a fondness for neomanic complication over archaic simplicity. We need to understand the everlasting solidity of such a solution.

Making talk less cheap—Looking at the spoils—Corporations with random acts of pity?—Predict and inverse predict

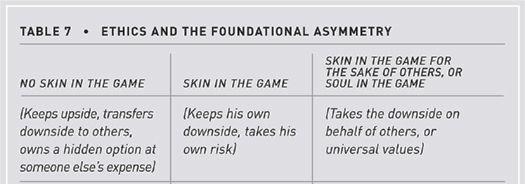

This chapter will look at what we are getting ourselves into when someone gets the upside, and a different person gets the downside.

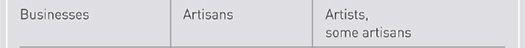

The worst problem of modernity lies in the malignant transfer of fragility and antifragility from one party to the other, with one getting the benefits, the other one (unwittingly) getting the harm, with such transfer facilitated by the growing wedge between the ethical and the legal. This state of affairs has existed before, but is acute today—modernity hides it especially well.

It is, of course, an agency problem.

And the agency problem, is of course, an asymmetry.

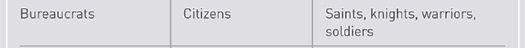

We are witnessing a fundamental change. Consider older societies—those societies that have survived. The main difference between us and them is the disappearance of a sense of heroism; a shift away from a certain respect—and power—to those who take downside risks for others. For heroism is the exact inverse of the agency problem: someone elects to bear the disadvantage (risks his own life, or harm to himself, or, in milder forms, accepts to deprive himself of some benefits) for the sake of others. What we have currently is the opposite: power seems to go to

those, like bankers, corporate executives (nonentrepreneurs), and politicians, who steal a free option from society.

And heroism is not just about riots and wars. An example of an inverse agency problem: as a child I was most impressed with the story of a nanny who died in order to save a child from being hit by a car. I find nothing more honorable than accepting death in someone else’s place.

In other words, what is called sacrifice. And the word “sacrifice” is related to

sacred,

the domain of the holy that is separate from that of the profane.

In traditional societies, a person is only as respectable and as worthy as the downside he (or, more, a lot more, than expected,

she

) is willing to face for the sake of others. The most courageous, or valorous, occupy the highest rank in their society: knights, generals, commanders. Even mafia dons accept that such rank in the hierarchy makes them the most exposed to be whacked by competitors and the most penalized by the authorities. The same applies to saints, those who abdicate, devote their lives to serve others—to help the weak, the deprived, and the dispossessed.

So

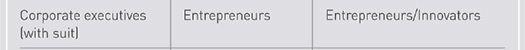

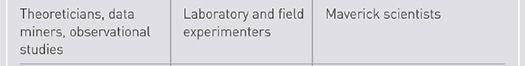

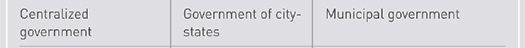

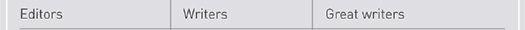

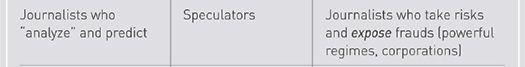

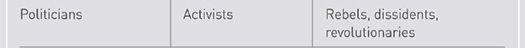

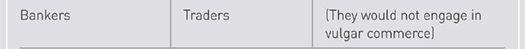

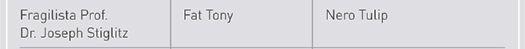

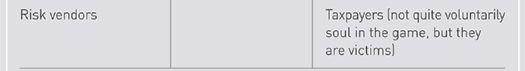

Table 7

presents another Triad: there are those with no skin in the game but who benefit from others, those who neither benefit from nor harm others, and, finally, the grand category of those sacrificial ones who take the harm for the sake of others.