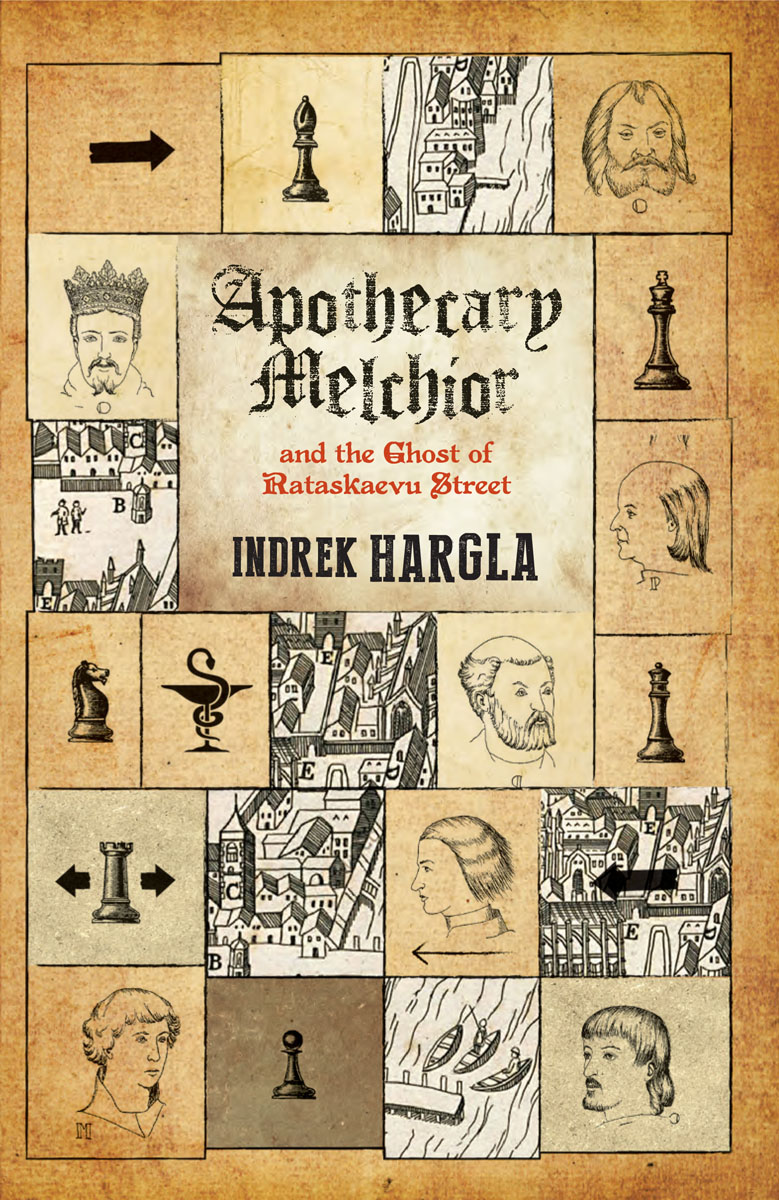

Apothecary Melchior and the Ghost of Rataskaevu Street

Read Apothecary Melchior and the Ghost of Rataskaevu Street Online

Authors: Indrek Hargla

and the Ghost of Rataskaevu Street

Talinn, 1419. What links the Master of the Quad Dack Tower, a prostitute and a Flemish painter to a haunted house on Rataskaevu Street? All three claim to have seen a ghost near the house, and each is found dead soon afterwards.

In the aftermath of these seemingly supernatural events, Melchior Wakenstede, apothecary and assistant bailiff, takes it upon himself to unearth the truth. When he finds a castrated murder victim outside the house, the scene of some violent murders decades earlier, he begins to research the history of those events and attempts to find out whether, as some believed, ghosts truly can reap their revenge upon the living. When a powerful and pious old merchant dies, Melchior suspects a connection between this and the other deaths.

In his attempts to solve the riddle Melchior becomes embroiled in the conflicts and rivalries between the religious orders, the merchants' guilds and the Teutonic Knights as they vie with one another for control of the town. He finds himself in a convent, a brothel, witnesses the desecration of graves and eventually comes up against the Ghost of Rataskaevu Street itself, and, as the threads begin to unravel, what he discovers is more incredible and more horrifying than any legend.

INDREK HARGLA is one of the most prolific and best selling Estonian authors working today â mostly in the fields of science fiction, fantasy and crime. He is best known internationally for his âApothecary Melchior' series, which now runs to six volumes with film adaptations currently in preparation.

Apothecary Melchior and the Ghost of Rataskaevu Street

is the second in the series to be published in English.

TALLINN

AD 1419

T

HE

YEAR OF

our Lord 1419 saw somewhat more peaceful times in Livonia. The Victual Brothers had been expelled from the Baltic Sea, but long-distance trade was still fraught with danger, as the vogts and vassals of the maritime strongholds had got into the habit of impounding ships close to shallow coastal waters. Letters were exchanged between these towns demanding that marauders be punished and their goods given back. Livonia had been gripped by famine in recent years; the arid summers had caused the crops to fail. This had driven more of the peasantry than ever before to seek work and bread within the town's walls. There were years of famine in the succeeding decades, too; hunger was a serious and very real danger during the Middle Ages.

The greater building boom in Tallinn was over by 1419, but the enlargement of the churches and the strengthening of the town walls continued apace. The grand new Guildhall of the Great Guild of merchants had recently been completed, a symbol of the power and significance of the trading community. Extensive building work had begun at St Nicholas's; a new choir and apse were being constructed on the eastern side of the church. The Dominicans had begun the extension of St Catherine's Church. The town walls, which had to be made thicker and higher all the time to keep pace with developments in weaponry, now needed even more reinforcement around St Michael's Convent. Just at the boundary where the town's land met that of the Teutonic Order, at Pirita â which in

those days was called Maarjaorg in Estonian and Mariendal in Swedish â work had finally begun in 1417 on the construction of St Bridget's Convent. But the Master of the Livonian Order himself â the branch of the Teutonic Order based in Toompea â had to intervene to encourage the town to permit stones to be brought from the limestone quarry at Lasnamäe. The first buildings had appeared at Pirita in 1400; the construction of the convent was advocated by the Order, the Order's vassals, the local Swedes and several merchants of Tallinn and Toompea; the town fathers, however, rejected it. It had taken nearly twenty years to overcome the opposition and negotiate diplomatically. One of the nine townsmen who had applied for the construction of the convent had been a certain Laurentz Bruys, âa miserable and pious merchant', who, however, died just as the major construction work was beginning.

There was constant quarrelling over territory between the Prussian branch of the Teutonic Order, Poland and Lithuania, but, after the defeat at Tannenberg, the influence of the Order was considerably reduced. In 1419 stormy negotiations continued over the Treaty of Thorn, which, despite being discussed before the papal legate and the Council of Constance, had so far not led anywhere. Peacetime in the Order's lands was brief, for as early as 1419 the Hussite War broke out near its borders, and in 1422 yet another war with PolandâLithuania. Whether Tallinn, too, sent its own troops is not known for sure. As early as 1348 the Master of Livonia had given the town privileges so that they would not have to fight against the Lithuanians and Russians, but this did not exempt it from fighting against Poland. It is certainly known that in one later war â of which there were many between Poland and the Order â Tallinn sent the town's musicians to the battlefield. The Livonian branch of the Order was striving for greater independence and kept increasing distance from the wars going on to the south. Erik of Pomerania, King of the Northern Lands, formed an alliance with Poland against the Order in the summer of 1419, but through the intervention of Emperor Sigismund it was never put into effect. Sigismund did not agree to the plan to liquidate the Order â and,

incidentally, Estonia would have had to submit to the Danish crown if that had taken place. In February 1419 the Archbishop of Riga invited representatives of towns in the region to appear before a meeting of the Livonian Diet for the first time, and from that year on envoys from Tallinn did take part in those councils.

In the Tallinn records for March 1419 is to be found an entry recording the death at the harbour bulwark of a certain Gils de Wredte â he who âpainted the walls at the Church of the Holy Ghost' â followed by an intriguing comment which might be interpreted from the Middle Low German text to mean âhe who saw the ghost'.

The material in this novel has also been inspired by one document of Tallinn Town Council dated 1404. The Council warns its colleagues in Magdeburg about a certain citizen of Tallinn, Untherrainer, who was said to have killed several people and who âthrashes with a whip'. The Tallinn Council recommends that Untherrainer be hanged. Whether there is any connection between this Untherrainer and the Cristian Untherrainer who was executed as a heretic at Fürstenwald in 1413 it has not been possible to establish.

Rataskaevu Street seems to have been notorious since ancient times. The Baltic German historian Johannes von Werensdorff wrote in 1876 that there was known to be a house from the Middle Ages where several women were walled into the cellar alive. Werensdorff does not name his source; he might simply have been passing on a folk tradition. One of the most widespread legends concerning Rataskaevu Street tells of a house where the devil held a wedding and struck up a dance, and since then the house was said to have been haunted. A later legend is known of some evil spirit that lived in the well (the

kaev

of the name Rataskaev, literally wheel well or windlass well) and who would flood the town if sacrifices were not made to him.

The mentality of a medieval person differed greatly from that of someone today â maybe because the spirit of man was younger and more unstable. In those days God was loved more fervently and one's enemy was hated more fiercely. People could be overcome by inexplicable mass hysteria, such as when flagellants went around

in procession whipping themselves into semi-consciousness in a religious-sexual ecstasy, thinking that they were saving the world, or when, during the Children's Crusades, thousands of youngsters died from exhaustion and hunger.

Life in a Hanseatic town proceeded according to a fixed rhythm. The Catholic calendar reflects a logical economic life that stems from the rules of nature. From about April to October the Baltic Sea was navigable, and the main trading activity took place in the summer when people were freer from religious obligations. Holy days and the longer fasts were in the first half of the year, and that was also the time when stored foods started to perish or run out. The forty-day fast before Easter enforced austerity and economy; it made one think about one's resources and avoiding extravagance. In the winter and early spring people could and did take more care of their souls. At the end of spring the town awoke from its piety and began working, which brought bread to the table and made it possible to survive through the next winter.

THE QUAD DACK TOWER AT ST MICHAEL'S CONVENT,

2 AUGUST, LATE EVENING

D

EATH

SMELLED OF

sweet putrefying blight, of something old and mouldy. Death reeked just like a dead dog wrapped in yeasty dough, and it was near by. It greeted Tobias Grote, tenderly, invitingly, even alluringly.

They had met before, many times. Tobias Grote was a soldier, and he calculated that at least nine men and one woman had died by his hand. But this Death which was now calling to him was ⦠unjust. Yes, he thought he should not die yet, not because of a ghost, not like that. He saw something like a white shape clad in a death shroud approaching him, and he knew the stench of its stale mouldiness, its insipid rotting stink, and he felt its pain, which was more than one human could bear.

Pain can probably kill you, Tobias Grote, Master of the Quad Dack Tower, was thinking now. It is pain, after all, that kills a man, when he takes so much of it that the body and soul can no longer endure it, and it is simpler to give in to the pain, simpler to die.

And then? What happens next? Will I find out whether everything the Church tells us is really true? Will the Redeemer be waiting for me, and will he tell me why he sent that stinking apparition after me, why he marked me out in that way, why my pathfinder to the heavenly kingdom was this revelation which had, after all, once been human?

Yes, Master Grote was sure of that. That the one chosen as his angel of death had once been a person of flesh and blood, and he

had no idea why he was being punished in this way at the last moment of his life, why he had been sent for. The ghost had appeared to him yesterday for the first time, wanting to announce something â but what? He had not understood it then, but now he understood, at his own last moment, why it seemed so tall and at the same time so short. Now he understood. The ghost had come to call him away, to tell him that his time had come. From some corner of his memory Tobias Grote recalled an old hymn; he thought of his brothers, who must be waiting for him in death, his three younger brothers, who had all died in the days of the sea battles.

Come, pitiless death, enfold me,

Tell my brothers I am on my way,

Let them wait for me in the icy silence,

Let those who remain alive mourn.

He could not remember where or when he had heard that verse â in the tavern, in church, from his brothers in arms or somewhere else â and it did not seem important. The only thing that made him wonder, the only thing throbbing in his head as he awaited his last breath in inhuman pain, was the question of why had this ghost, this apparition with its rotten stench, come to beckon him and not his brothers, not his father or mother.

Only yesterday, yes, it had been only yesterday when the ghost risen from the dead appeared to him for the first time, for one brief moment, and then it had vanished and left Master Grote dismayed and puzzled. Tobias Grote was not yet fifty, and his health was robust, thank God, although his old sword wounds made him ill in bad weather and he was half-blind in the left eye. Nevertheless, he was in full vigour, a strong man, who could hold a battleaxe in his hand, knew how to load and shoot a firearm, and he knew what loyalty and an oath of fidelity were. He had sworn loyalty to the town of Tallinn, and he was proud that the simple son of a tailor from near the town of Travemünde had become the master of a

tower in the walls of one of the finest fortresses of the Teutonic Order. And the master of no ordinary or out-of-the-way tower but one of the biggest and strongest towers, almost the foundation of the Order's fortifications, defending the town and the holy sisters.