Arcadia

Authors: Tom Stoppard

Tags: #Drama, #European, #English; Irish; Scottish; Welsh, #General

Arcadia

Arcadia

Tom Stoppard

ISBN 0-571-16934-1

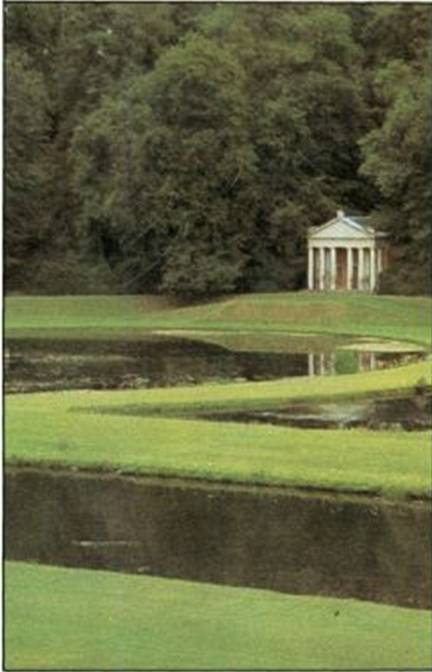

In a large country house in Derbyshire in April 1809 sit

Lady Thomasina Coverly, aged thirteen, and her tutor, Septimus Hodge. Through

the window may be seen some of the ‘500 acres inclusive of lake’ where Capability

Brown’s idealized landscape is about to give way to the ‘picturesque’ Gothic

style: ‘everything but vampires’, as the garden historian Hannah Jarvis remarks

to Bernard Nightingale when they stand in the same room 180 years later.

Bernard has arrived to uncover the scandal which is said to

have taken place when Lord Byron stayed at Sidley Park.

Tom Stoppard’s absorbing play takes us back and forth between

the centuries and explores the nature of truth and time, the difference between

the Classical and the Romantic temperament, and the disruptive influence of sex

on our orbits in life—‘the attraction which Newton left out’.

Arcadia

opened at the Lyttelton Theatre, Royal

National Theatre, on 13 April 1993. The cast was as follows:

THOMASINA COVERLY | Emma Fielding |

Septimus HODGE | Rufus Sewell |

JELLABY | Allan Mitchell |

EZRA CHATER | Derek Hutchinson |

RICHARD NOAKES | Sidney Livingstone |

LADY CROOM | Harriet Walter |

CAPTAIN BRICE, RN | Graham Sinclair |

Hannah JARVIS | Felicity Kendal |

CHLOE COVERLY | Harriet Harrison |

Bernard NIGHTINGALE | Bill Nighy |

VALENTINE COVERLY | Samuel West |

GUS COVERLY | Timothy Matthews |

AUGUSTUS COVERLY | |

Director | Trevor Nunn |

Designer | Mark Thompson |

Lighting | Paul Pyant |

Music | Jeremy Sams |

Scene One

A room on the garden front of a very large country house

in Derbyshire in April 1809. Nowadays, the house would be called a stately

home. The upstage wall is mainly tall, shapely, uncurtained windows, one or

more of which work as doors. Nothing much need be said or seen of the exterior

beyond. We come to learn that the house stands in the typical English park of

the time. Perhaps we see an indication of this, perhaps only light and air and

sky.

The room looks bare despite the large table which

occupies the centre of it. The table, the straight-backed chairs and, the only

other item of furniture, the architects stand or reading stand, would all be

collectable pieces now but here, on an uncarpeted wood floor, they have no more

pretension than a schoolroom, which is indeed the main use of this room at this

time. What elegance there is, is architectural, and nothing is impressive but

the scale. There is a door in each of the side walls. These are closed, but one

ofthefrench windows is open to a bright but sunless morning.

There are two people, each busy with books and paper and

pen and ink, separately occupied. The pupil is

Thomasina coverly,

aged

13. The tutor is

Septimus HODGE,

aged 22. Each has an open book. Hers is

a slim mathematics primer. His is a handsome thick quarto, brand new, a vanity

production, with little tapes to tie when the book is closed. His loose papers,

etc, are kept in a stiff-backed portfolio which also ties up with tapes.

Septimus has a tortoise which is sleepy enough to serve

as a paperweight.

Elsewhere on the table there is an old-fashioned

theodolite and also some other books stacked up.

Thomasina: Septimus, what is carnal embrace?

Septimus: Carnal embrace is the practice of throwing one’s

arms around a side of beef.

Thomasina: Is that all?

Septimus: No ... a shoulder of mutton, a haunch of venison

well hugged, an embrace of grouse ...

caro, carnis;

feminine; flesh.

Thomasina: Is it a sin?

Septimus: Not necessarily, my lady, but when carnal embrace

is sinful it is a sin of the flesh, QED. We had

caro

in our Gallic Wars—‘The

Britons live on milk and meat’—‘

lacte et carne vivunf

. I am sorry that

the seed fell on stony ground.

Thomasina: That was the sin of Onan, wasn’t it, Septimus?

Septimus: Yes. He was giving his brother’s wife a Latin lesson

and she was hardly the wiser after it than before. I thought you were finding a

proof for Fermat’s last theorem.

Thomasina: It is very difficult, Septimus. You will have to

show me how.

Septimus: If I knew how, there would be no need to ask

you.

Fermat’s last theorem has kept people busy for a hundred and fifty years, and I

hoped it would keepjyow busy long enough for me to read Mr Chater’s poem in

praise of love with only the distraction of its own absurdities.

Thomasina: Our Mr Chater has written a poem?

Septimus: He believes he has written a poem, yes. I can see

that there might be more carnality in your algebra than in Mr Chater’s ‘Couch

of Eros’.

Thomasina: Oh, it was not my algebra. I heard Jellaby telling

cook that Mrs Chater was discovered in carnal embrace in the gazebo.

Septimus:

(Pause)

Really? With whom, did Jellaby

happen to say?

(Thomasina

considers this with a puzzled frown.)

Thomasina: What do you mean, with whom?

Septimus: With what? Exactly so. The idea is absurd. Where

did this story come from?

Thomasina: Mr Noakes.

Septimus: Mr Noakes!

Thomasina: Papa’s landskip gardener. He was taking bearings

in the garden when he saw—through his spyglass—Mrs Chater in the gazebo in

carnal embrace.

Septimus: And do you mean to tell me that Mr Noakes told the

butler?

Thomasina: No. Mr Noakes told Mr Chater.

Jellaby

was

told by the groom, who overheard Mr Noakes telling Mr Chater, in the stable

yard.

Septimus: Mr Chater being engaged in closing the stable

door.

Thomasina: What do you mean, Septimus?

Septimus: So, thus far, the only people who know about this

are Mr Noakes the landskip architect, the groom, the butler, the cook and, of

course, Mrs Chater’s husband, the poet.

Thomasina: And Arthur who was cleaning the silver, and the

bootboy. And now you.

Septimus: Of course. What else did he say?

Thomasina: Mr Noakes?

Septimus: No, not Mr Noakes. Jellaby. You heard Jellaby telling

the cook.

Thomasina: Cook hushed him almost as soon as he started. Jellaby

did not see that I was being allowed to finish yesterday’s upstairs’ rabbit pie

before I came to my lesson. I think you have not been candid with me, Septimus.

A gazebo is not, after all, a meat larder.

Septimus: I never said my definition was complete.

Thomasina: Is carnal embrace kissing?

Septimus: Yes.

Thomasina: And throwing one’s arms around Mrs Chater?

Septimus: Yes. Now, Fermat’s last theorem—

Thomasina: I thought as much. I hope you are ashamed.

Septimus: I, my lady?

Thomasina: If

you

do not teach me the true meaning of

things, who will?

Septimus: Ah. Yes, I am ashamed. Carnal embrace is sexual

congress, which is the insertion of the male genital organ into the female

genital organ for purposes of procreation and pleasure. Fermat’s last theorem,

by contrast, asserts that when

x,y

and

z

are whole numbers each

raised to power of n, the sum of the first two can never equal the third when

n

is greater than 2.

(Pause.)

Thomasina: Eurghhh!

Septimus: Nevertheless, that is the theorem.

Thomasina: It is disgusting and incomprehensible. Now when I

am grown to practise it myself I shall never do so without thinking of you.

Septimus: Thank you very much, my lady. Was Mrs Chater down

this morning?

Thomasina: No. Tell me more about sexual congress.

Septimus: There is nothing more to be said about sexual congress.

Thomasina: Is it the same as love?

Septimus: Oh no, it is much nicer than that.

(One of the side doors leads to the music room. It is the

other side door which now opens to admit

JELLABY,

the butler.)

I am teaching, Jellaby.

Jellaby: Beg your pardon, Mr Hodge, Mr Chater said it was urgent

you receive his letter.

Septimus: Oh, very well, (Septimus

takes the letter.)

Thank

you.

(And to dismiss

Jellaby.) Thank you.

Jellaby:

(Holding his ground)

Mr Chater asked me to

bring him your answer.

Septimus: My answer?

(He opens the letter. There is no envelope as such, but

there is a ‘cover” which, folded and sealed, does the same service.

Septimus

tosses the cover negligently aside and reads.)

Well, my answer is that

as is my custom and my duty to his lordship I am engaged until a quarter to

twelve in the education of his daughter. When I am done, and if Mr Chater is

still there, I will be happy to wait upon him in—

(he checks the letter)—

in

the gunroom.

Jellaby: I will tell him so, thank you, sir.

(Septimus folds the letter and places it between the

pages of ‘The Couch of Eros’.)

Thomasina: What is for dinner, Jellaby?

Jellaby: Boiled ham and cabbages, my lady, and a rice pudding.

Thomasina: Oh, goody. (Jellaby

leaves.)

Septimus: Well, so much for Mr Noakes. He puts himself forward

as a gentleman, a philosopher of the picturesque, a visionary who can move

mountains and cause lakes, but in the scheme of the garden he is as the

serpent.

Thomasina: When you stir your rice pudding, Septimus, the

spoonful of jam spreads itself round making red trails like the picture of a

meteor in my astronomical atlas. But if you stir backward, the jam will not

come together again. Indeed, the pudding does not notice and continues to turn

pink just as before. Do you think this is odd?

Septimus*. No.

Thomasina: Well, I do. You cannot stir things apart.

Septimus: No more you can, time must needs run backward, and

since it will not, we must stir our way onward mixing as we go, disorder out of

disorder into disorder until pink is complete, unchanging and unchangeable, and

we are done with it for ever. This is known as free will or self-determination.