Ardor (18 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

* * *

For the Vedic seers, cosmogony was not the traditional tale of primordial times, but a literary genre that allowed for an indefinite number of variants. And all were compatible—

iva

, “so to speak.” Or at least, all converged on one ever-present point—the sacrifice. Sacrifice was the breath of the multiple cosmogonies: stories of a specific sacrifice that at the same time were the foundation of the sacrifice. There are many different versions in one and the same work about what originally happened to Praj

ā

pati. And each new version is meant to explain some detail about the world as it is. If the stories about Praj

ā

pati were not so richly varied, the world would be poorer, less vital, less capable of metamorphosis. The more variegated the origin, the denser and more impenetrable is the texture of everything. It is generally described as “the three worlds”: the sky, the earth, and atmospheric space. All that happens takes place between these three layers of reality. And this would be quite enough to complicate the picture, since the relationships between the three levels are extremely dense.

But the ritualist is a man of doubt. For every movement he performs, he is goaded by a question: is this

the

gesture to perform? Will this gesture cover the whole of reality? Or will there still be a further reality that this gesture cannot touch? Hence, at one point, the ritualist refers to a

fourth world.

If this world existed, it would be a disturbing revelation, since everything done up to that point had involved only three worlds. Isn’t the mere existence of the fourth enough to frustrate such a vision? And won’t perhaps the fourth world feel outraged about never having been taken into consideration? Yet “uncertain it is whether the fourth world exists.” An irresolvable doubt as to the very existence of an entire world is therefore acknowledged. What should be done? The ritualist is used to opening up a way—perhaps a temporary one—through this maze. If the existence of the fourth world is uncertain, then “uncertain is also what is done in silence.” A further movement must then be added to the movements carried out while reciting a formula, which is done in silence. That gesture will be the recognition that the fourth world

might

exist. That is enough to go further, on toward other gestures. But that silent doubt lingers behind all speculation. Until all of a sudden, from one side, and with a nonchalance typical of the esoteric, a sentence appears with the long-awaited answer: “Praj

ā

pati is the fourth world, beside and beyond these three.” The answers to riddles have a peculiar feature: they become riddles themselves, and even more far-reaching. This is the case here. If Praj

ā

pati is the “fourth world”—and the existence of the fourth world is “uncertain”—the existence of Praj

ā

pati himself would be uncertain. If we trace back to the one who created living beings, we do not encounter something more sure and solid, but something whose existence we can indeed legitimately put in doubt, something we can nevertheless ignore without this upsetting in any way the workings of everything, of those “three worlds” with which we are constantly involved. The theological daring of the ritualists is dazzling: implicit in the mystery is its capacity to instill doubt as to its own existence, the ability to allow everything to exist without having to refer to the mystery itself. Nothing protects a mystery better than the denial of its very existence.

* * *

Praj

ā

pati: the background noise of existence, the steady hum that goes before every sound graph, the silence behind which we perceive the workings of a mind that is

the

mind. It is the

id

of what happens, a fifth column that spies on and sustains every event.

V

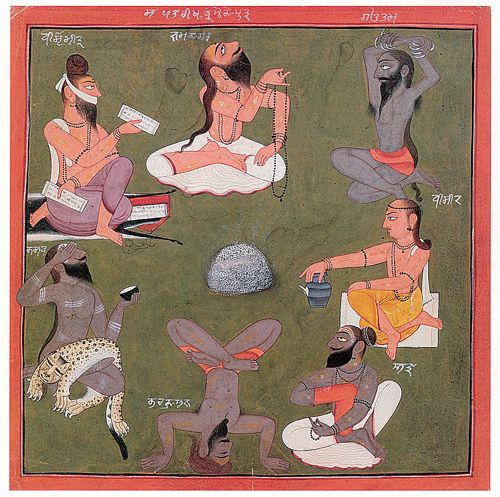

THEY WHO SAW THE HYMNS

The hymns of the

Ṛ

gveda

were said to have been

seen

by the

ṛṣ

is.

The

ṛṣ

is

may therefore be described as “seers.” They saw the hymns in the same way as we see a tree or a river. They were the most disconcerting, least easily explainable beings in the Vedic cosmos. Chief among them were the Saptar

ṣ

is, the Seven who lived in the stars of the Great Bear, who have some affinity with the Seven Greek Sages, with the Islamic

abd

ā

ls

, and with the Seven Akkadian Apkallus of the Apsu. But something in the very nature of the

ṛṣ

is

was an epistemological scandal: they alone were allowed to belong to the unmanifest and at the same time take part in the events of everyday life, which they secretly ruled.

And this itself was alarming: that a metaphysical category, the

asat

, the “unmanifest,” was a category of beings that had a name. Hermann Oldenberg felt an immediate need to clear away any inappropriate comparisons: “This non-being was of quite a different kind to Parmenides’ non-being—and there is very little here of his rigor in discussing with passionate seriousness the non-being of the non-existent.” Oldenberg’s embarrassment was justified and we can still detect the pride of someone who had been educated following the nineteenth-century idea of classicism. With the

ṛṣ

is

, in fact, one has to go in quite another direction. Only the starting point is the same: the

asat

which Oldenberg translates as “non-being.” Now, if

asat

refers to the

ṛṣ

is

, the nonbeing would refer to a category of beings. These, in turn, would correspond with the “vital breaths,”

pr

āṇ

as

—and here we plunge into the realm of physiology. Moreover, nonbeing acts through the practice of

tapas

, the “ardor” that overheats consciousness. Too many palpable elements are attributed to this nonbeing. And above all: too many elements that then continue to appear and operate in the existent, in whatever exists. A network of cracks thus forms in it, as if to suggest that not everything that appears in the existent belongs to the existent. These metaphysical passages were not congenial to the West. Oldenberg could barely restrain his indignation: “The non-being starts to think, to act so readily, in spite of any

Cogito ergo sum

, like an ascetic preparing to perform some magic trick.” Oldenberg thought he was expressing a paradox, or even an absurdity. But his words could have been interpreted as a plain, accurate description. The

ṛṣ

is

watched him from high up in their stars, with that exasperating seriousness of theirs, more derisive even than sarcasm.

* * *

The Vedic seers saw the hymns of the

Ṛ

gveda

in much the same way that others among them

found

the rites that were later to be celebrated and studied. Knowledge was an encounter with something preexisting, sight of which the gods now and then allowed. They were not interested in educating and guiding the human race, which they looked upon with mixed feelings, sometimes benevolent sometimes hostile, so that “from time to time, following the whim of the moment, the celestial power communicates to mankind first one, then another fragment of inestimable knowledge” (Oldenberg again).

How, though, was this knowledge deposited and arranged? The metrics are too perfect, the vocabulary too varied, the overall composition too complex, so it must be presumed that the

Ṛ

gveda

—the concrete product of that knowledge—was developed over a long period that began before even the descent into India, in other regions toward the northwest, and in other climates. Traces of these events, enigmatic as always, can be spotted in certain hymns. The most dazzling ancient poetry is already imitating an archaic style, as if the earliest Greek statuary were that of the Master of Olympia. When it first came to us, passed down through thousands of memories, unaltered, the word of the

ṛṣ

is

seemed already to be a “tributary of a long, learned tradition.” And the

Ṛ

gveda

was already a

sa

ṃ

hit

ā

, a “collection,” an anthology that “mixes together an older, less differentiated, mass that heads of clans or schools would have drawn from at different moments.”

* * *

When something (or someone) is created, produced, emanated, composed—especially at the beginning of the world—the Vedic texts repeat countless times that this happened through

tapas

, “ardor.” But what is

tapas

? Many Indologists have avoided the question, having been led astray by the Christianizing translations (“asceticism,” “penance,” “mortification”) that began with the first nineteenth-century editions (and can still be found today). After all, it is well-known that ascetics, penitents, and disciples practicing self-mortification are to be found in India more than anywhere else. They, it is said, are the latest practitioners of

tapas.

And the question would seem to be resolved with a general reference to spirituality.

Now

tapas

is certainly a form of asceticism in the original sense of “exercise,” but it is a very particular exercise that implies the developing of heat.

Tapas

is akin to the Latin word

tepor

—and indicates fervor, ardor. Those who practice

tapas

could be described as “ardent.” They generate a heat that can become a devastating blaze. This is what happened with various

ṛṣ

is

who every so often shook the world.

The

ṛṣ

is

are not gods, they are not demons, they are not men. But they often appear earlier than the gods, indeed earlier than the being from which the gods had emanated; they often display demonic powers; they often move about like people among people. The Vedic texts feign indifference toward these incompatibilities, as if they didn’t recognize them, perhaps because the hymns of the

Ṛ

gveda

appear to be composed by the

ṛṣ

is

themselves. Elsewhere, in other places and periods, we search in vain for figures that combine their characteristics, all converging into one: incandescence of mind. With this the

ṛṣ

is

were capable of attacking all other beings, whether gods, men, or animals.

The

ṛṣ

is

reached an unattainable level of knowledge not just because they thought certain thoughts but because they

burned.

Ardor comes before thought. Thoughts are given off like steam from a boiling liquid. While the

ṛṣ

is

were sitting, motionless, and contemplating what was happening in the world, whirling inside them was a scorching spiral that would one day break off to become the hymns of the

Ṛ

gveda

or the “great sayings,”

mah

ā

v

ā

kya

, of the Upani

ṣ

ads.

There is nothing more misleading than to imagine the

ṛṣ

is

, and above all the Seven Seers, as calm and affable beings, detached from the world’s vicissitudes. On the contrary, if the world continues on its course, it is primarily due to the immense reserves of

tapas

that the Seven Seers channel, moment by moment, into the veins of the universe. But this

tapas

can occasionally be directed against the world itself—and wreak havoc. Nor can it be said that the incandescent mass of ardor lets itself be steered by the

ṛṣ

is.

When Vasi

ṣṭ

ha, one of the Seven Seers, wishes to kill himself in despair over the death of his children, his

tapas

prevents him from doing so. He threw himself off a very high cliff, only to land on a vast lotus, as if on a soft bed. His

tapas

was too powerful to allow its bearer to kill himself.