Read Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Are Lobsters Ambidextrous? (4 page)

In practice, most Cornish fowls are crossbred with Plymouth Rock fowls.

Dr. Roy Brister, director of research and nutrition at Tyson Food, Inc., told

Imponderables

that

all

the chicken we eat has the Cornish White Rock as one of its ancestors. Cornish fowl are prized because they are plump, large-breasted, and meaty. Other breeds are too scraggly and are better suited for laying eggs. Most of the Cornish game hens now sold in the United States

are actually less than thirty days old and weigh less than one pound after they are cooked.

According to the USDA’s

Agriculture Handbook

, Cornish game hens are raised and produced in the same way as broilers. But because they are sold at a smaller weight, the cost per pound to process is higher for the producer and thus for the consumer.

But let’s face it. It’s a lot easier to get big bucks for a product with a tony name like “Rock Cornish game hen” than it is for “chick” or “baby broiler.” If veal were called “baby cow,” its price would plummet overnight. Dr. Brister speculates that the creation of “Cornish Game Hens” was probably a marketing idea in the first place.

While we are pursuing our literary equivalent of “A Current Affair,” one more scandal must be unleashed. Not all those Cornish game hens are really hens. Legally, they can be of either sex, although they are usually females, because the males tend to be larger and are raised to be broilers. In fact, if immature chicks get a little chubby and exceed the two-pound maximum weight, they get to live a longer life and are sold as broilers.

Submitted by an anonymous caller on the Mel Young Show, KFYI-AM, Phoenix, Arizona

.

Why

do boxer shorts have straight frontal slits and briefs have complicated “trap doors”?

All that infrastructure on the briefs is what keeps you from in-decent exposure charges. Even though most briefs and boxers sold in the U.S. are made out of the same material (cotton-polyester blends), briefs are knitted and boxers are woven. The two techniques yield different wear characteristics.

Boxers are built for comfort and won’t stretch unless elasticized bands are added. But as Janet Rosati of Fruit of the Loom’s Consumer Services told

Imponderables

, briefs are intended as support garments and are designed to stretch. Without all the

reinforcements, or “trap doors,” as our correspondent so elegantly put it, the opening on briefs would tend to gape open at embarrassing and unfortunate times. ’Nuf said?

Submitted by Josh Gibson of Silver Spring, Maryland

.

Why

have auto manufacturers eliminated the side vents from front door windows?

As Frederick R. Heiler, manager of public relations for Mercedes-Benz of North America, put it, “Vent wings have gone the way of the starter crank handle.” Sure, there are the occasional exceptions, such as the 1988 Mercury, which resurrected this feature. But on the whole, it has now been superseded by the vent setting on air-conditioning systems (the device that propels air onto your shins rather than onto your face).

Why the change? The main reason, believe it or not, is fuel economy. In order to meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s fuel requirements, American car manufacturers will change just about anything in order to achieve a better aerodynamic design. Heiler remarks that “designers found they could do without the air turbulence of the extra window post and hardware.” Especially at high speeds, air turbulence, including turbulence caused by leaving the “regular” windows down, lowers fuel economy significantly.

Representatives at Ford and Chrysler add that since most automobiles now come equipped with air conditioning and flow-through ventilation systems, the need for vent wings has been obviated (thus reducing the flak the companies received for eliminating them). Our cars are now like modern office buildings—often run without windows ever being opened.

An official at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, who preferred to remain anonymous, corroborated the above but listed two more reasons why auto manufacturers dumped vent wings: One, a single, bigger plate of glass costs less than a smaller piece with a vent wing; and two, the vent wing was the perfect place for thieves to insert the old coat hanger.

Submitted by Tom Ferrell of Brooklyn, New York. Thanks also to Ronald C. Semone of Washington, D.C.; H.J. Hassig of Woodland Hills, California; and Richard Nitzel of Daly City, California

.

Why

do the Oakland Athletics’ uniforms have elephant patches on their sleeves?

The elephant may be the symbol of the Republican party, but partisan politics was the last thing on Connie Mack’s mind when the legendary owner of the Philadelphia Athletics decided to adopt the white elephant as his team’s insignia. Rival New York Giants manager John McGraw boasted that the Athletics, and the fledgling American League, to which they belonged, were unworthy competitors, and indicated that Mack had spent a fortune on a team of “white elephants.”

Mack got the last laugh. The A’s won the American League pennant in 1902. A few years later, the elephant’s image appeared on the team sweater. In 1918, Mack first emblazoned the elephant on the left sleeve of game uniforms.

The elephant image became so popular that in 1920, Mack

eliminated the “A” on the front of the jersey and replaced it with a blue elephant logo. Four years later, he changed it to a white elephant. After a few years of playing more like a bunch of thundering elephants than a pennant contender, Mack de-pachydermed his players’ uniforms.

No A’s uniform sported an elephant again until 1955, when the Kansas City A’s added an elephant patch to their sleeves. But when the irascible Charlie Finley bought the A’s in the early 1960s, he replaced the elephant with the image of an animal more befitting his own personality—the mule.

But you can’t keep a good animal down. According to Sally Lorette, of the Oakland A’s front office, the current owners of the A’s resurrected the same elephant used by the Kansas City Athletics in time for the 1988 season. The mascot did the job for the Oakland A’s just as it had for Connie almost a century ago. Since 1988, the A’s have won three American League pennants and one championship.

Submitted by Anthony Bialy of Kenmore, New York. Thanks also to a caller on the Jim Eason Show, KGO-AM, San Francisco, California

.

Why

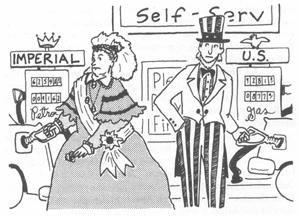

is the imperial gallon bigger than its American counterpart?

The English have never been particularly consistent in their standards of weights and measures. In fact, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, England changed its definition of a gallon about as often as Elizabeth Taylor changes wedding rings. (Before then, Kings Henry VII and VIII and Queen Elizabeth I had also changed the definition of a gallon.)

Colonialists in America adopted the English wine gallon, based on the size of then-used hogsheads (barrels) of 231 cubic inches. The English, who also recognized the larger ale gallon of 282 cubic inches, finally settled the mess in 1824 by eliminating the ale and wine gallons completely and instituting the imperial gallon, defined as the volume of ten pounds of water at the temperature of 62 degrees Fahrenheit, the equivalent of about 277.420 cubic inches.

Meanwhile, Americans were basking in the freedom of a

participatory republic but were saddled with an anachronistic wine gallon. In both the English and American systems, one gallon equals four quarts and eight pints, but English portions were significantly larger.

To compound the standardization problem, the British decided to use the same system to measure liquid and dry substances. They redefined a bushel as eight gallons. In the U.S., bushels, pecks, and all those other measurements we hear in Broadway songs but not in everyday speech are used only to measure grains and other dry commodities.

Perhaps this was England’s revenge for the American Revolution. By the time the English finally got their act together and laid out a simple, sensible system of measurement, Americans had already committed to the inferior, old English system.

Submitted by Simon Arnold of Los Angeles, California

.

Why

do painters wear white uniforms?

Often, when we confront practitioners of an industry with an Imponderable about their line of work, they are befuddled. “I’d never stopped to think about that” is a typical reply.

Such was not the case with painters we contacted about this mystery. Nobody seemed to know for sure how the practice started, but we were lavished with theories about why “whites” made sense. In fact, when we contacted the International Brotherhood of Painters & Allied Trades, we were stunned to find out that after they posed the same question to their membership, their

Journal

was filled with responses in the April and May 1985 issues. Our thanks to the many members of IBPAT and other painters we contacted for help in answering what, on the basis of our mailbag, is a burning question of the 1990s.

One advantage that just about everyone could agree on is that white connotes cleanliness. A painter, after all, removes dirt and crumbling plaster before applying paint. Many painters

compared the purity of their “whites” to the uniforms of nurses, chefs, and bakers. Philadelphia painting contractor Matt Fox told

Imponderables

that a white uniform is like a badge that says, “There’s no paint on me, so I’m doing my job.” Obviously, it is as hard to hide paint smeared on a white uniform as it is to hide a ketchup stain on a chef’s apron.

The white uniform is also a sign of professionalism, one that distinguishes painters from other craftspeople. One IBPAT member wrote that in the early twentieth century, his father often encountered part-time, nonunion workmen trying to horn in on the painting trade. These workers, usually moonlighting, wore blue bib overalls or other ordinary work clothes not related to the paint trade. By contrast, “Our men certainly looked professional in their white overalls, white jackets, and black ties.” Even today, most professionals prefer crisp white uniforms (even if they’ve shed the tie), while odd-job part-timers might don blue jeans and a T-shirt.

Of course, a color other than white could still look clean and professional. And at first glance, white seems like precisely the wrong color—by wearing white, you “broadcast” any color you spill. True, but remember that the majority of the time (estimates are 70 to 80 percent), painters are dealing with white paint. And what other color uniform is going to look better when splattered with white paint?

Painters deal with other white substances more than likely to be deposited on their uniforms. Painter Jerry DeOtis presumes that the tradition of “whites” began in eighteenth-century England, when buildings were routinely whitewashed. Irving Goldstein of New York City adds:

Plaster, lime, spackle, and compound are also white. Repairing and sanding existing walls creates a fine white powder; therefore wearing “painters whites” enables these materials to blend into the uniform.