Armageddon (10 page)

Gavin disliked the plan from the outset: “It looks very rough. If I get through this one, I will be very lucky. It will, I am afraid, do the airborne cause a lot of harm.” The Polish Parachute Brigade commander, Stanislaw Sosabowski, whose men were scheduled to reinforce the British on the third day of the operation, also expressed fierce reservations. The British regarded the Pole as an absurd figure. Staff officers sometimes giggled like schoolboys when Sosabowski held forth emotionally at planning meetings. “But later,” said John Killick, “we realized that some of the things he said, some of the difficulties he raised, were serious and valid.”

If legend is correct, that “Boy” Browning suggested before the drop that Montgomery’s plan represented an attempt to advance “a bridge too far,” then the remark confirms his critics’ views about the general’s meagre intellect. Market Garden could not succeed partially, by winning some of the bridges north-east of the British front. To justify the whole operation, it was essential to seize the Rhine crossing at Arnhem. Anything less would be meaningless, an assault into a cul-de-sac.

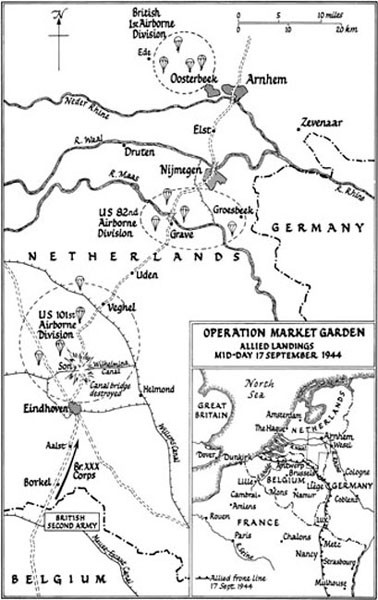

The overwhelming flaw in the plan was that it required the British Second Army’s tanks to relieve in turn the 101st Airborne at Eindhoven and Son, the 82nd at Nijmegen and the 1st Airborne at Arnhem along a single Dutch road. It was impossible for the vast armoured column to leave the tarmac, because the adjoining countryside was too soft to accommodate tanks, and in some places was heavily wooded. On the advance to Arnhem, the overwhelming superiority of the allied armies over the enfeebled Germans became irrelevant. The outcome would be determined by a contest between the defenders and the needle point of the British force—which effectively meant a single squadron of tanks and its supporting infantry. If the advance bogged down, 1st Airborne Division would be left unsupported to hold the most distant objective—the bridge at Arnhem—for longer than any force in the short history of airborne warfare. The plan called for the tanks of XXX Corps to get there in forty-eight hours. Even that interval seemed perilously long if the Germans could deploy tanks against the paratroopers.

These hazards were known to the men who planned the operation, above all to Montgomery himself, normally the most cautious of commanders. His chief of staff, Freddie de Guingand, was ill in England. De Guingand telephoned from his sickbed to suggest that the airborne operation was being launched too late to exploit German disarray, and that XXX Corps’s push to Arnhem was being made on too narrow a front. Montgomery dismissed these strictures, asserting that de Guingand was “out of touch.” The field-marshal’s enthusiasm for Market Garden was so uncharacteristic that it has puzzled some historians. Yet his motives do not seem hard to read. Bitterly chastened by his removal from the Allied ground command, he was determined to sustain the primacy of his own role in the battle for Germany. In consequence, he focused his entire attention on the issue of how the enemy’s front might be broken in Holland, where the British stood. He displayed no interest in other opportunities further south, on the front of Bradley’s U.S. 12th Army Group. David Fraser, a Grenadier officer in north-west Europe, later a general and biographer of Brooke, said: “Montgomery’s jealousy of Eisenhower affected his decisions at every stage.” This seems just.

The British field-marshal, like most of his fellow commanders, believed that the Germans in the west were broken and that the Allied task was now to exploit the victory achieved in Normandy only three weeks earlier. In the euphoria of September 1944, Montgomery and his colleagues concluded that the normal rules governing engagement with the German army could be suspended. The British planners persuaded themselves that the hard part was over, that they were now engaged in gathering the spoils of victory. They threw away all that they had learned since 1939 about the speed of reaction of Hitler’s army, its brilliance at improvisation, its dogged skill in defence, its readiness always to punish allied mistakes. Market Garden was an operation that might have succeeded triumphantly, as several British African offensives succeeded triumphantly, if the defenders had been Italians of Mussolini’s army. Instead, however, on the ground in Holland were soldiers of Hitler.

T

HE FIRST ELEMENTS

of three airborne divisions landed by parachute and glider in the early afternoon of Sunday 17 September, ninety minutes before the tanks spearheading XXX Corps crossed their start line on the Meuse–Escaut Canal. Private Bob Peatling, a signaller with the British 2 Para, was thrilled to be seeing action at last. Although he had joined the army in 1942, he had never heard a shot fired in earnest: “We feared we’d never get into it unless we got cracking. I had no idea what battle would be like, but there was a wonderful feeling that Sunday.” A keen boy scout in his childhood, Peatling packed in his kit for Arnhem two books on scouting, to read in his leisure hours on the battlefield. One was entitled

Rovering to Success

.

Jack Reynolds’s mortar platoon of the South Staffordshires was part of the air-landing brigade of 1st Airborne. Lieutenant Reynolds, a former local government clerk from Chichester in Sussex, was a veteran of twenty-two. On his first parachute jump, he had seen a man in his “stick” plunge to the ground in a fatal “roman candle.” Later he survived the bloodbath of the 1943 airborne landings in Sicily. Reynolds observed cheerfully that his platoon, who would have to carry into battle the terrific burden of three-inch mortars and ammunition, were “the biggest and thickest men in the battalion.” He felt uncomfortably aware that the Staffords were not the unit they had been two years earlier: “The young recruits and officers seemed so innocent. In my platoon many blokes were fresh out of training. We had lost a lot of good chaps in Sicily and Italy. There wasn’t the same spirit now. How could there be?” It is often asserted that 1st Airborne Division was an elite. Yet in truth even its own men had reservations about the quality of several units, and especially of their commanders.

Captain Julius Neave was adjutant of the 13th/18th Royal Hussars, one of Montgomery’s armoured units. Neave wrote in his diary: “There is no doubt in [our commanding officer’s] mind that the war will be over this year, and this is undoubtedly the prevalent view everywhere . . . Yesterday we were told that the present operation ‘Market Garden’ would be the last Corps battle, and it is anticipated that now we shall be split into Battle Groups to liquidate isolated resistance.”

Every man who parachutes into action faces a dramatic mental adjustment between the tranquillity of the world he quits on take-off and the white heat of battle which he encounters a few hours later. Captain John Killick found it unreal to sit among comrades reading the Sunday newspapers in their comfortable mess in England until trucks arrived to take them to the airfield. He felt little apprehension: “We were young. We were light-hearted.” Partly because so many transport aircraft were shifting fuel to the armies in France, the landings required three separate lifts, spread over three days. This badly weakened the fighting power of the Allied airborne divisions in the first vital hours. The shortage of capacity made it seem all the more grotesque that Browning used thirty-six aircraft to move his own headquarters in the first wave. He should have insisted that the Allied transport fleet make two trips, rather than one, on the first day. This would have been perfectly feasible, at the cost of some strain upon aircrew. The initial landings were overwhelmingly successful: 331 British aircraft and 319 gliders, together with 1,150 U.S. aircraft and 106 gliders, landed 20,000 men in good order between Eindhoven and Arnhem.

Lieutenant Jack Curtis Goldman was flying a Waco glider carrying a communications jeep of the U.S. 504th Regiment. Like so many of his generation “Goldie,” a twenty-one-year-old from San Angelo, Texas, had always yearned to fly: “More than life itself, I had wanted to be a fighter pilot.” Imperfect eyesight caused him to be rejected for combat pilot training, but the recruiting sergeant said he would overlook the problem if Goldman would sign up for gliders. He found the experience “like trying to ride a brahman bull at a rodeo. Anyone who has ever experienced turbulence in an aircraft, just multiply it by ten and you will have some idea what a glider was like. Yet most of us . . . were eager to fly into combat, particularly those who were single and had no responsibilities. For me, the war was a big adventure, and September 17th, 1944

,

was to be one of the most fantastic adventures of my life.”

Above Holland that Sunday, on tow at 120 m.p.h., the young Texan found an 82nd Airborne jeep driver squeezing into the cockpit behind him. “I’m praying for you,” the soldier said. “Why?” “Because if you get hit, I don’t know how to fly this glider.” They cut the tow at 1,000 feet, and went into a steep, spiralling dive to avoid a stall. Goldman tried to align the glider with the plough lines he saw beneath him, but found the ground rushing up to meet him at right angles to the furrows. Bump, lurch, bump, they hurtled across the field in their flimsy vessel of plywood and canvas, already hearing explosions. Then they were down, just north of the Maas river, a mere six miles from the Dutch border with Germany. They flipped the nose hatches. The terrified jeep driver bore them full-tilt towards the shelter of a wood. Goldman met some fellow pilots. They exulted wildly in having done their job and survived: “We were really happy, happy campers at that moment.” Unlike British glider pilots, their American counterparts were not expected to fight in the ground battle. Their job was over once they had landed their clumsy craft. Many disappeared on sprees in Holland and Belgium that lasted for days.

Bob Peatling of 2 Para was awed by the spectacle of 1st Airborne’s drop: “It was a wonderful sight to see everybody coming down.” At first, after he himself hit the ground amid the cloud of parachutes filling the sky and collapsing on the earth, he heard no firing. The British descended on to fields and open heathland some six miles north-west of Arnhem bridge, with the Rhine between themselves and XXX Corps. Everybody converged on the rendezvous where Colonel John Frost was blowing his hunting horn, and formed files for the advance into Arnhem. When they began to move, they made slow progress: “We kept meeting bits of opposition, and having to stop. It was a long, hot afternoon. But I thought: ‘This is better than England!’ ” Peatling was not the only one dismayed by 2 Para’s sluggish pace. The divisional commander, Major-General Roy Urquhart, expressed his concern in the first hours.

Corporal Harry Trinder’s glider overshot the landing zone and crashed into a pine wood. He found himself trapped behind the cockpit bulkhead in the wreckage, and it was some time before he could be cut free. Before the battle even started, Trinder was out of it with a badly cut eye and a clutch of broken ribs. He was laid among the wounded who were already coming in, including some whose injuries were plainly mortal. Trinder noticed that “those whom the MO thought were completely beyond hope were given a massive injection of morphine, and put on one side to die.” He thought himself lucky.

John Killick dumped his parachute and walked up to divisional headquarters on the Arnhem landing zone, to find a divisional signals officer reciting monotonously and vainly into a handset: “Hello, Sunray, are you receiving me?” This was the first evidence of the shameful, almost comprehensive failure of 1st Airborne Division’s wireless communications, which was to dog every aspect of the battle which followed.*

4

Killick set out to walk alone into Arnhem, in pursuit of Frost’s men. A few yards down the road, he found an abandoned German BMW motorcycle. Commandeering this, he sped eastwards. A mile further on, he saw a string of German army signposts beside a house, and wandered in. This was the Tafelburg Hotel, Field-Marshal Walter Model’s headquarters at Oosterbeek, hastily abandoned by Army Group B as they saw the first paratroopers descending. Not a soul was in sight. Killick switched on a radio set, and idly picked at some meatballs on the dining-room table. After starting his day reading the Sunday papers in England, “I felt in an absurd position, now to be listening to the BBC and eating the Germans’ lunch.”

Sergeant George Schwemmer, a panzergrenadier with 10th SS Panzer at Arnhem, had been drafted to the division as a replacement after its withdrawal from Normandy. Although Schwemmer was thirty-one, he had managed to stay out of the army until 1944, performing labour service. He would have been more than happy to continue his wartime career road-building and helping with the harvest. Now instead, however, he found himself reluctantly commanding a platoon of panzergrenadiers, most of them young replacements. More than a few of of 10th SS Panzer’s soldiers were not eager Nazis, but “odds and sods” like Schwemmer, scraped together from the depots. He himself was billeted in a house on the edge of Arnhem, and ran out when he heard firing. His first glimpse of the attackers was a wrecked glider which had crashed in a field. He saw German soldiers gesturing to each other as they deployed. Dutch civilians were craning out of every house. Schwemmer shouted brusquely to them to get their heads in and close the windows. Then he ran to muster his unit, which was quickly plunged into street fighting for the town.