As Nature Made Him (34 page)

Read As Nature Made Him Online

Authors: John Colapinto

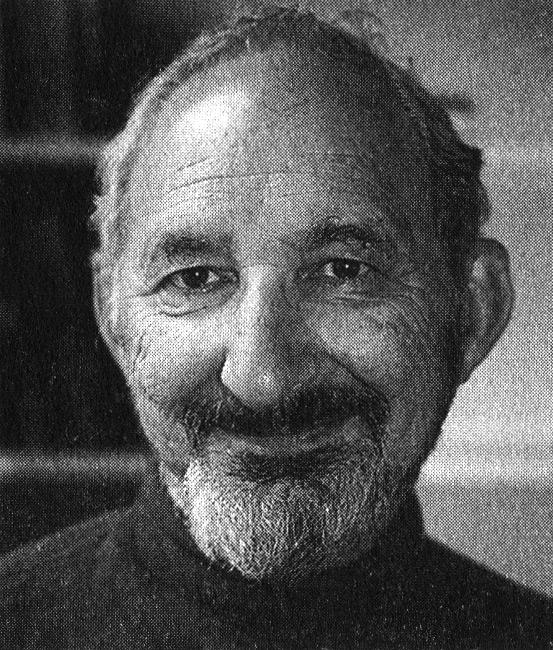

Dr. John Money

Dr. Milton Diamond

Brian, Ron, and Janet on their way to what would be the family’s final trip to Baltimore, in May 1978. Brenda, the photographer, was careful to stay on the opposite side of the lens at this stage of her life.

Brenda at age twelve, shortly after she started estrogen therapy to promote the feminization of her figure.

Brian and Brenda at age fourteen, shortly before they were told the truth of Brenda’s birth.

David and Brian in May 1980 at their uncle’s wedding, where David made his public debut as a boy. David still carries the evidence of the binge-eating he had done, as Brenda, to disguise his breasts. They would be surgically removed five months later, and testosterone injections would soon make David catch up in height to his twin.

David and Brian, May 1980, at their uncle’s wedding.

David at age eighteen.

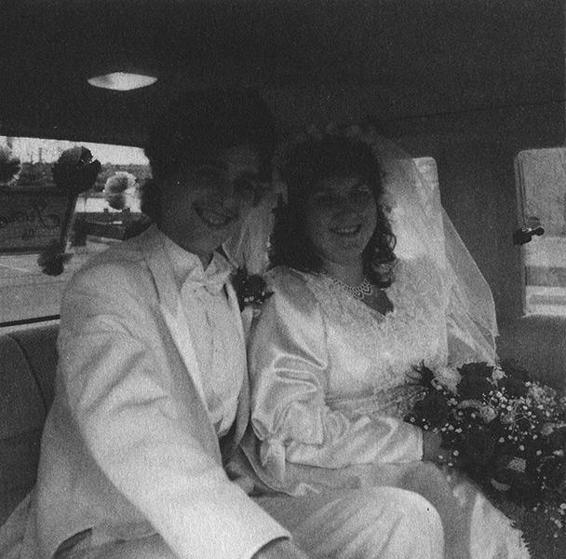

David and Jane on their wedding day, 22 September 1990. It was Jane’s reaction to the truth about David’s past that convinced him of her “true heart.”

Afterword

A

S ITS TITLE WOULD SUGGEST

,

As Nature Made Him

places considerable emphasis on the role that biology plays in the shaping of human sexuality. In that respect, the book was meant as a clear corrective to the extreme nurturist stance of the 1960s and 1970s, when biological influences on gender identity and sexual orientation were dismissed altogether—a view which still informs much of the thinking of the lay public even today. For me, learning about the role of prenatal hormones in hardwiring sexual behavior was eye-opening, and a degree of the urgency I felt in writing the book derived from the satisfying sense that I was bringing to readers facts probably unknown to them.

Yet while I consider David’s case to be among the strongest evidence yet available for the biological underpinnings of gender, I reject any reading of the book that reduces his story to simpleminded biological determinism—whether that reductionism is meant as a compliment to the book, or as a criticism. One reviewer, for instance, praised

As Nature Made Him

for showing that “gender is indeed biologically based and not learned at all.” Yet another criticized the book for the same supposed message: “[W]hen it comes to nature-nurture, I believe it’s not so much a matter of being right, but a matter of, emphasis. A deliberate emphasis on nurture is politically healthier, especially for women.” The first statement is preposterous (how can learning play no role “at all” in how an individual comes to understand his position in society?); the second equally so. Political health, or correctness, should play no role in scientific debate—unless, of course, the debate is purely academic theorizing, a kind of intellectual Ping-Pong, in which case nothing rides on it. Unfortunately, within the context of infant sex reassignment,

everything

rides on it, since it is only by continuing to assert nurture’s primacy over nature that physicians can continue to assign sexual identities to newborns through surgery, psychological engineering, and hormones. As David’s story shows, that is a risky practice indeed.

Happily, the medical profession has, in the wake of the book’s publication, shown a heretofore unprecedented willingness to re-examine the practice of infant sex reassignment—and to listen to the testimony of former patients. ISNA founder Cheryl Chase has been invited to speak to the American Academy of Pediatrics, and has joined a group of urologists to form the North American Task Force for Intersexuality, which is collecting long-term data from some two hundred cases of sex-reassigned people and evaluating the long-term effects of the procedure. In May 2000, she spoke at a conference at Johns Hopkins, where she delivered the final talk at the annual meeting of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society—perhaps the strongest evidence to date that the medical profession as a whole is willing to reassess the efficacy of infant sex reassignment—and the relative roles of genetics and environment in the making of boys and girls, men and women.

None of this is to suggest that nurture plays no role in gender identity. Virtually every page of

As Nature Made Him

contains an environmental cue or clue that helped to reinforce what Brenda’s prenatally virilized brain and nervous system were telling her. Among these environmental cues, I would include the presence of an identical twin brother who so closely resembled Brenda and yet was, mystifyingly, of the opposite sex; the scarred and unfinished state of her genitals which contributed to her conviction that

something

was unusual about her assigned gender; the teasing and ostracization of peers and classmates who jeered at her for her masculinity; the growing realization on the part of Ron and Janet, around the time of Brenda’s seventh birthday, that the experiment was a failure; the trips to Johns Hopkins, where her genitals and sexual identity were of such obsessive interest to Money and his students; and indeed, the second-class status assigned to females in society—a condition that leads many dispirited girls to wish (around the time of puberty) that they could be boys. All of these factors, I’m convinced, played a role in undermining the experiment. I attribute the case’s final and complete collapse, however, to the pressing insistence of Brenda’s biological maleness—her awakening sexual attraction to girls; her inchoate but adamant aversion to possessing breasts and a vagina. For how many children, at the exquisitely awkward age of fourteen, will insist, upon threat of suicide, that they undergo full sex change, in plain view of neighbors, family, and friends? This almost incomprehensible act of courage on Brenda’s part speaks more convincingly than any other piece of evidence to the emphatic demands of our biology, and to the necessity that we—all of us—be allowed to live as we feel we must.

Indeed, it was this very courage of David’s which was my prime motivation in writing the book. Despite its medical-scientific context, I’ve always believed that this story transcends the incessant quibbling over the nature/nurture debate. David’s is a story about identity in its largest sense—not simply

sexual

identity. His story, for all its uniqueness, is a universal one, and reminds us how it is every person’s individual responsibility to define for himself who he is, and to assert that against a world that often opposes, ridicules, oppresses, or undermines him. It is perhaps as much to David’s innate will and strength, as it is to his prenatally organized brain and nervous system, that he owes his survival; not many children, at seven years old, could have faced down a man of John Money’s famously persuasive temperament. Yet he did so, as he staunchly refused to undergo a surgical procedure (vaginoplasty) which he instinctively knew would seal him into an identity not his own. For me, the emotional crescendo of the story comes in that moment directly after Ron Reimer revealed the stunning truth of her birth to Brenda—and her first question was not about

how

or

why

her parents could have made such a decision; it was not to ask how such a devastating circumcision accident could have occurred. Instead, she asked her birth name. She asked, in effect,

Who am I

? Kept so long from this ultimate knowledge, it was only through learning this essential truth that David was then able to begin assembling a life for himself.