Ash: A Secret History (153 page)

As fast as it happens in the field of combat, Floria reached out and grabbed one of the kneeling hart’s tines. The sharp bone slashed up at her arm.

“

Florian!

” Ash screamed.

The alaunt let go of the flank and closed its square jaws around the beast’s hind leg. The bite severed the main tendon. The white hart’s body jerked back, falling sideways.

Floria del Guiz, still holding its horns, lifted Ash’s wheel-pommel sword and shoved the point in behind the hart’s shoulder. She laid all her body-weight into it; Ash heard her grunt. Blood sprayed, Floria thrust, the sword bit deep in behind the shoulder, and down into the heart.

Ash tried to move: could not.

All lay together in a huddle: Floria sprawled on her knees, panting; the hart with the sharp metal blade and hilt protruding from its body lying across her; the alaunt worrying the hind leg, bone cracking in the cold, quiet air.

The hart jerked once more and died.

Blood ran slowly, cooling. The hart’s relaxing body let a last flux of excrement out on to the cold earth.

“Get this bloody dog away from me!” Floria protested weakly, and then suddenly looked up at Ash’s face, astonished. More than astonished: frightened, pained, illuminated. “What—?”

Ash was already snapping her fingers at the huntsman. “You! On your feet. Blow the death. Get the rest of them here for the unmaking.”

5

She put her empty hands to her sword-belt, stunned with the astonishment of that.

“Florian, what part of the butchering is the augury? When do we know if we’ve got a Duke?”

A bright flash of colour blinked over the whitethorn bushes: someone’s velvet hat. A second later and the rider appeared, men on foot with him; twenty or thirty Burgundian noblemen and women; and the other hunters took up the call, blowing the death until the harsh sound echoed back from the crag and rang out far and wide across the wildwood.

“We haven’t got a Duke,” Floria del Guiz said.

She sounded suffocated.

What alerted Ash, made everything clear to her, was a sudden internal silence; no choral voices thundering in her mind, only a bitter, bitter quiet.

Floria raised her gaze from her bloody hands, stroking the dead hart’s neck. Ash saw her expression: a moment of gnosis. She had bitten her lip bloody.

“A Duchess,” Floria said, “we have a Duchess.”

The wind hissed in the whitethorn spines. The cold air smelled of shit, and blood, and dog, and horse. A great hush took the voices around Ash, the men and women on foot and riding falling silent, all in the space of a second. The huntsmen blowing the death fell quiet. All of them silent: chests heaving, breath blowing white into the cold air. Their flushed faces were full of amazement.

Two men-at-arms in Olivier de la Marche’s livery rode their bay geldings into the narrow gap between the thorn bushes. De la Marche himself followed. He dismounted, heavily. Men caught his reins. Ash turned her head as the Burgundian deputy of the Duke walked past her, his creased, dirty face alight.

“You,” he said. “You are she.”

Floria del Guiz shifted the hart’s body off her knees. She stood up. The black alaunt flopped at her feet. She pushed it away from the white hart’s body with the toe of her boot, and it whined, the only sound in all the stillness. She squinted at Olivier de la Marche, in the pale autumn sunlight.

Gently and formally, he said, “Whose is the making of the hart?”

Ash saw Floria rub at her eyes with bloody hands, and look around at the men behind de la Marche: all the great nobles of Burgundy.

“I did it,” Floria said, no force in her voice. “The making of the hart is mine.”

Bewildered, Ash looked at her surgeon. The woman’s woollen doublet and hose were filthy with mud, soaked with animal blood, ripped with thorns and branches; and twigs clung in her hair, coif gone missing somewhere in the wild hunt. Floria’s cheeks reddened, finding herself the centre of all gazes; and Ash stepped forward, business-like, gripped her sword and twisted the blade to pull it out of the hart’s body, and said under cover of that movement, “Is this trouble? You want me to get you out of here?”

“I wish you could.” Floria’s hand closed over her arm, bare skin against cold metal. “Ash, they’re right. I made the hart. I’m Duchess.”

In Ash’s mind, there is no sound of the Wild Machines. She risks it, whispers under her breath, “Godfrey … are they there?”

–

Great is the lamentation in the house of the Enemy!

Great

is the

—

Angry voices drown him out: voices that speak as the thunderstorm does, in great cracks of rage, but she can understand none of them: they rage in the tongue used by men when Gundobad was prophet – and they are faint, as a storm is faint, over the horizon.

“Charles died,” Floria said with complete certainty. “A few minutes ago. I felt it when I put the death-blow in. When I knew.”

The sun, weak in autumn though it is, is a perceptible warmth now on Ash’s bare face.

“Someone’s Duke or Duchess,” Ash breathed. “Someone is – someone’s stopping them again. But I don’t know why! I don’t understand this!”

“I didn’t know, until I killed the hart. Then—” Floria looked at Olivier de la Marche, a big man in mail and livery, the arms of Burgundy at his back. “I know now. Give me a minute, messire.”

“You are she,” de la Marche said, dazedly. He swung round to face the men and women crowding close. “No Duke, but a Duchess! We have a Duchess!”

The sound of their cheer ripped the breath out of Ash’s body.

That it had been some kind of political trick, was her first thought; that assumption vanished in the roar of acclamation. Every face, from huntsman to peasant woman to Duke’s bastards, shone with a gladness that could not be faked.

And

someone

is doing – whatever it is that Charles was doing; whatever it is that holds the Wild Machines back.

“Christ,” Ash grumbled, under her breath. “This lot aren’t joking. Fuck, Florian!”

“

I’m

not joking.”

Ash said, “Tell me.”

It was a tone of voice she had used often, over the years, requiring her surgeon to report to her, requiring her friend to tell her the thoughts of her heart; and she shivered, inside padding and armour, at the sudden thought

Will

I ever talk to Florian like this again?

Floria del Guiz looked down at her red-brown hands. She said, “What did you see? What were you hunting?”

“A hart.” Ash stared at the albino body on the mud. “A white hart, crowned with gold. Sometimes Hubert’s Hart.

6

Not this, not until the end.”

“You hunted a myth. I made it real.” Floria lifted her hands to her face, and sniffed at the drying blood. She raised her eyes to Ash’s face. “It was a myth and I made it real enough for dogs to scent. I made it real enough to kill.”

“And that makes you Duchess?”

“It’s in the blood.” The woman surgeon snuffled a laugh back, wiped her brimming eyes with her hands, and left smears of blood across her cheeks. She edged closer to Ash as she stood staring down at the hart, which none of the huntsmen approached for butchering.

More and more of the hunt staggered uphill to the thorn-sided clearing below the crag.

“It’s Burgundy,” Floria said, at last. “The blood of the Dukes is in all of us. However much, however little. It doesn’t matter how far you travel. You can never escape it.”

“Oh yeah. You’re dead royal, you are.”

The sarcasm brought Floria back to something of herself. She grinned at Ash, shook her head, and rapped a knuckle on the Milanese breastplate. “I’m pure Burgundian. It seems that’s what counts.”

“The blood royal. So.” Ash laughed, weakly, from the same overwhelming relief, and pointed a steel-covered finger at the hart’s body. “That’s a pretty shabby-looking miracle, for a royal miracle.”

Floria’s face became drawn. She spared a glance for the growing throng, mutely waiting. The wind thrummed through the whitethorn. “No. You’ve got it wrong. The Burgundian Dukes and Duchesses don’t perform miracles. They prevent them being performed.”

“Prevent—”

“I

know,

Ash. I killed the hart, and now I know.”

Ash said sardonically, “Finding a hart, out of season, in a wood with no game; this

isn’t

a miracle?”

Olivier de la Marche came a few steps closer to the hart. His battle-raw voice said, “No, Demoiselle-Captain, not a miracle. The true Duke of Burgundy – or, as it now seems, the true Duchess – may find the myth of our Heraldic Beast, the crowned hart, and from it bring this. Not miraculous, but mundane. A true beast, flesh and blood, as you and I.”

“Leave me.” Floria’s voice was sharp. She gestured the Burgundian noble to go back, staring up at him with bright eyes. He momentarily bowed his head, and then stepped back to the edge of the crowd and waited.

Watching him go, colour caught Ash’s eye. Blue and gold. A banner bobbed over the heads of the crowd.

Shamefaced, Rochester’s sergeant plodded out to stand beside Ash with her personal banner. Willem Verhaecht and Adriaen Campin shouldered their way through to the front row, faces taking on identical expressions of relief as they saw her; and half the men at their backs were from Euen Huw’s lance, and Thomas Rochester’s.

In all her confusion, Ash was conscious of a searing relief.

No assault on the Visigoth camp, then. They’re alive. Thank Christ.

“Tom – where are the fucking Visigoths! What are

they

doing?”

Rochester rattled off: “’Bout a bow-shot back. Messenger came up. Their officers are in a right panic over something, boss—”

He broke off, still staring at the company surgeon.

Floria del Guiz knelt down by the white hart. She touched the rip in its white coat.

“Blood. Meat.” She held her red hands up to Ash. “What the Dukes do…

I

do … isn’t a negative quality. It makes, it – preserves. It preserves what’s true, what’s real. Whether…” Floria hesitated, and her words came slowly: “Whether what’s real is the golden light of the Burgundian forest, or the splendour of the court, or the bitter wind that bites the peasant’s hands, feeding his pigs in winter. It is the rock upon which this world stands. What is

real.

”

Ash stripped off her gauntlet and knelt beside Floria. The coat of the hart was still warm under her fingers. No heartbeat; the flow of blood from the death-wound had stopped. Beyond the body, not flowers, but muddy earth. Above her, not roses, but winter thorn and rowan.

Making the miraculous mundane.

Ash said slowly, “You keep the world

as it is.

”

Looking up into Floria’s face, she surprised anguish.

“Burgundy has its bloodline, too. The machines bred Gundobad’s child,” Floria del Guiz said. “And this is an opposite. The Machines want a miracle to wipe out the world, and I – I make it remain sure, certain, and solid. I keep it what it is.”

Ash took Floria’s cold wet hand between her own hands. She felt an immediate withdrawal that was not physical: only Floria giving her a look that said,

What happens now? Everything is different between us.

Sweet Christ.

Duchess.

Slowly, her eyes on Floria’s face, Ash said, “They had to breed a Faris. So that they could attack Burgundy the only way it can be attacked: on the physical, military level. And when Burgundy is removed … then they can use the Faris. Burgundy is only the obstacle. Because ‘winter will not cover all the world’ – won’t cover us here, not while the Duke’s bloodline prevents the Faris making a miracle.”

“And now there’s no Duke, but there is a Duchess.”

Ash felt Floria’s hands trembling in hers. The hazy overcast cleared, the white autumn sun throwing the shadows of thorns sharp and clear on the mud. Five yards beyond the sprawled body of the white hart, rank upon rank of people waited patiently. The men of the Lion company watched their commander, and their surgeon.

Floria, her eyes slitted against the sudden brilliance of the sun, said, “I do what Duke Charles did. I preserve; keep us quotidian. There’ll be no Wild Machines’ ‘miracles’ – as long as I’m alive.”

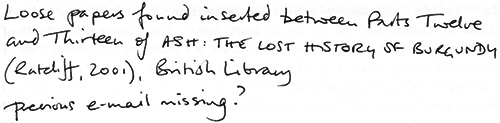

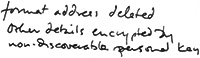

Message: #350 (Anna Longman)

Message: #350 (Anna Longman)