Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (42 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

1688-1757

of Prussia

Frederick Prince of Wales 1707-51

married

Augusta

of

Saxe-Gotha Anne

1709-59 married Prince

William IV of Orange Amelia Caroline George William 1711-86 1713-57 1717-18 Duke of

Cumberland 1721-65 Mary Louisa 1723-77 1724-51 married married

Landgrave King Frederick II Frederick V of Hesseof

Cassel Denmark

Augusta GEORGE III 1737-1813 1738-1820 married married the Duke of Charlotte

Brunswick of

Mecklenburg

-Strelitz Edward Elizabeth William Henry Louisa Frederick Caroline

Duke of

York and

Albany

1739-67

1741-59 Duke of Duke of 1749-68 1750-65 1751-75

1743-1805 1745-90 King married married Christian VII

Countess Anne of Denmark Waldegrave Horton

GEORGE III

25 October 1760 – 29 January 1820

King George III succeeded his grandfather at the age of twenty-two. In the early years of his reign, George was firmly under the thumb of his widowed mother, Augusta of SaxeGotha Princess of Wales and her alleged lover the Earl of Bute (George’s former tutor), who was appointed Prime Minister. They arranged for George to marry Duchess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom he first met on their wedding day. In 1762, their son, George, was born. Anticipating many more children, the new king bought Buckingham House in London for £21,000 as a private residence. He was right; there would be a total of fifteen children.

The signing of the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War. Pitt’s determination to pursue Britain’s enemies and their colonies outside Europe brought extraordinary rewards. Britain was confirmed in the conquest of Canada, various Caribbean islands plus huge territory in India, and also gained Senegal, Florida and Minorca. In Europe, Prussia (which retained Silesia) was now the dominant force; but Britain became the major colonial power across the world. Nevertheless, in the light of so many victories, in England the treaty terms were considered inadequate, and the unpopular Bute was forced to resign.

New Prime Minister Grenville found a novel way of raising money that would cause no problems with the electorate. He decided to tax the American colonists; all legal documents, newspapers and pamphlets would require a revenue stamp. Grenville’s justification was that the colonists should pay for the cost of their protection. In truth, little protection was needed; the French had been defeated and the colonists felt able to defend themselves against any hostile Indian tribes. Also, the legality of taxing those living outside Britain was questionable.

It did not go down well. Rioting started in the American colonies, followed by a boycott of British goods. Parliament was forced to reconsider the tax. Fortunately, Grenville had been replaced by Lord Rockingham, and the Stamp Act was repealed.

Pitt, ‘the Great Commoner’, a man who represented the people not the monarch, now became Prime Minister. However, he was not the success he had been when directing the war. He suffered a breakdown, and Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, led the Government during Pitt’s absence. Having learned nothing from the failed Stamp Act, Townshend decided to tax the colonists’ imports of glass, paper, lead, paint and tea. The tax revenue would help to pay the cost of maintaining the freedom of the seas, from which the colonists benefitted. Before he had any more bright ideas, Townshend died.

When Pitt recovered, he found out that the French had been allowed to take Corsica. It seemed a trivial matter at the time; but if Corsica had belonged to Britain, the great Corsican military leader (born just a year later) might one day have been directing British troops against the French rather than the other way round. It was only one of many matters that had gone wrong, but worst of all, Pitt’s mental health was damaged, and he had to resign.

As so often happened, the real culprit was rewarded; the Duke of Grafton became Prime Minister. It quickly became clear that he was not up to the job, and he was replaced by Lord North, a man who not only thought like the King, he even looked like the King.

Next, there was a serious personal problem for the King. George’s sister, Caroline, had been married off at the age of 15 to her cousin, King Christian VII of Denmark (his mother Louisa was a daughter of George II), despite concerns as to his mental state. Christian had to be persuaded to have intercourse with Caroline, which produced a son. He then took up with a prostitute, bringing her to court. Christian’s behaviour deteriorated by the day, involving low-life brothels, perversion and self-mutilation. Caroline was continually in distress at her husband’s preference for prostitutes and boys. Then Christian appointed a German doctor as his new physician. The physician, Johann Struensee, became Caroline’s lover. After little more than two years, Struensee had acquired such influence over the King that he exercised absolute power.

In January 1772, Struensee and Caroline were arrested. Struensee was executed, and George feared that Caroline would suffer the same fate. The navy prepared to attack Denmark. Then a deal was negotiated. Caroline was divorced and taken by a British ship to Hanover where she was confined for life in the Castle of Celle, much like her great-great-grandmother, Sophia Dorothea. At the age of twenty-three, Caroline conveniently died of scarlet fever in her castle prison.

More serious trouble was literally ‘brewing’ in America. North had repealed all Townshend’s import duties other than the tax on tea. In fact, the tax would raise little more than £3,000 a year, but it became a matter of principle for both sides. In December 1773, a tea ship belonging to the East India Company was attacked in Boston harbour by colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians, and the cargo was destroyed. North’s response to the Boston Tea Party was to close Boston harbour and put the Massachusetts Council under Crown control. That drove the other colonies to support Massachusetts. In England, initial sympathy for the colonists was diminished by what was seen as a criminal act.

Fighting started on a small scale between local militias and the British Army after soldiers had been sent to seize munitions at Concord. The war had begun. Pitt (who considered taxation of colonists to be unlawful) was for reconciliation, but he and his supporters were now in the minority.

It became increasingly difficult for Britain to cope with such a large area from so far away; instructions from London arrived in America weeks after the situation in the colonies had changed. Even worse, the hostilities polarised the two sides; the colonists’ resolve grew, and objection to taxation developed into a demand for independence. North wanted to resign in favour of Pitt, but the King was aware of Pitt’s sympathies and would not allow it; and then Pitt died (having given his name to Pittsburgh).

A General Election increased North’s majority. However, the election’s real significance lay in the entry to Parliament of Pitt’s second son, also named William Pitt, and therefore known as ‘Pitt the Younger’, at the age of twenty-one. From the day of his first speech, Pitt the Younger was destined to become one of the most brilliant of all members of parliament.

Meanwhile, problems were mounting in America. After several successes for British forces, the war started to go badly, with the colonists inspired by a man who had fought for Britain in the French and Indian War: George Washington. Then, with French support in troops and equipment, the colonists trapped Cornwallis and his army at Yorktown, and he surrendered. In England, support for the war collapsed.

North was compelled to resign; he was replaced by Lord Rockingham, who was a supporter of American independence. In July 1782, Rockingham died, and the Earl of Shelburne became Prime Minister with Pitt the Younger appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. By the end of the year, American independence, already a reality, was formally accepted. Thousands of colonists who had stayed loyal to the Crown had to be brought back to Britain for their own safety. Among them was Flora MacDonald, the Scottish woman who had helped Bonnie Prince Charlie to escape after Culloden. She had gone to live in America, and was a staunch Loyalist, her husband being a British officer.

Shelburne resigned, to be replaced by the Duke of Portland. After eight months he was replaced by Pitt the Younger. This was a man who had gone to Cambridge University at the age of 14, graduated at 17, been called to the Bar and become an MP at 21, been appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer at 23, and was now Prime Minister at 24.

Pitt had taken every opportunity to speak out against the American War, against corruption, for a reduction in taxation and for parliamentary reform. George would benefit from Pitt’s popularity.

George’s only problem was the hostility of the Prince of Wales, who always supported George’s enemies in Parliament. That problem became worse when the Prince announced that he had secretly married the twice-widowed Maria Fitzherbert, a Catholic. However, after the King’s brother, Henry Duke of Cumberland, married a commoner, George had insisted on the passing of the Royal Marriages Act, which provided that no descendant of George II (other than issue of princesses who had married into foreign families) could marry without the consent of the monarch; but if consent is refused to a person over the age of 25, that person may marry after giving the Privy Council one year’s notice unless both Houses of Parliament disapprove

32

. Consequently, the ‘marriage’ of the Prince of Wales was unlawful and ineffective.

In the country, the economy improved with the peace and all seemed well. It was 1778, and George’s carriage was arriving at his official residence, St James’s Palace. The carriage came to a halt, and a footman lowered the step so that George might climb down. As usual, there was a small crowd of onlookers hoping to catch sight of the monarch, maybe even to cheer him. Suddenly, a woman, Rebecca O’Hara, rushed forward holding a knife in her outstretched hand. Before she could stab George she was grabbed by two soldiers. On questioning the woman, it emerged that she believed that George had usurped the throne, to which she was entitled; although she could not explain the basis of her claim. She said that if she were not crowned queen, England would be deluged in blood for a thousand years. Sent to Bethlehem Hospital for the mentally ill

33

, she remained there for the rest of her life.

32

No application for consent has ever been refused; although there have been occasions when consent has not been sought in anticipation of refusal – the children were therefore illegitimate.

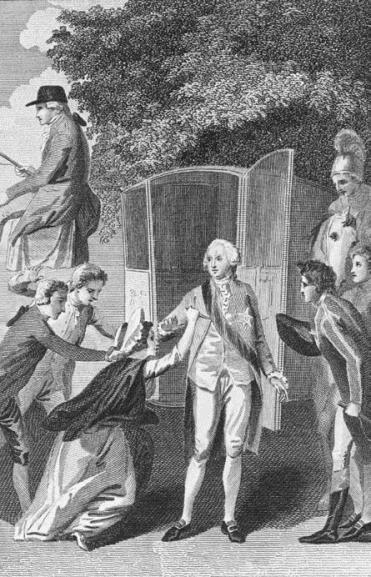

A similar incident occurred eight years later. Again, George was returning to St James’s Palace. His coach halted at the Garden Entrance. Without causing any disturbance, a woman manoeuvred her way to the front of the crowd. In her hand she had a rolled-up petition. After King George stepped down from the coach, he walked towards the woman to receive the petition. She held it out to the King. Then, with her other hand, the woman raised an ivory-handled knife and stabbed George. Fortunately, the weapon was a table knife of such poor quality that rather than plunge through George’s waistcoat and into his chest, the knife simply bent, causing no wound. It was snatched from the woman’s grasp, and she was held fast by a yeoman and a footman. George remained calm. In fact, his main concern was for his assailant’s safety. “The poor creature is mad. Do not hurt her; she has not hurt me,” he shouted.

George was right; Margaret Nicholson was quite mad. She was a needlewoman from Stockton-on-Tees. At the age of twelve she had been sent to work in a series of respectable households, ending up in the home of Sir John Sebright. Later, she was found to be having an affair with a footman, and was dismissed. Having lost her livelihood and her lover, she descended into poverty and insanity. She petitioned the King twenty times, begging for assistance, but received no reply. So she had gone to St James’s Palace to remonstrate with him. Asked what she wanted from the King, she replied: “That he would provide for me, as I want to marry and have children like other folks.” She was not prosecuted, instead she was sent to Bethlehem Hospital for life under the Vagrancy Act by order of the Home Secretary, even though the Act gave him no power to make such an order. Locked in a room, she was chained to the wall for five years. The chains were then removed, but she remained at Bethlehem until her death 37 years later.

33

Originally a priory, a hospital was attached to it in about 1329. In 1377 it was designated a hospital for ‘distracted patients’, who were chained to the wall and ducked in water or whipped when they were violent. It became a lunatic asylum in 1547 when the priory was dissolved.