At All Costs (34 page)

LIST OF SHIPS •••

The most heavily defended and heavily attacked naval convoy in history.

F

OURTEEN

M

ERCHANT

S

HIPS

Ohio | Torpedoed by an Italian submarine; bombed repeatedly; two shot-down Stukas crashed on her decks; suffered one direct hit and many near misses; lost engines and rudder; towed by destroyers, minesweepers, and tugboats into Malta; scuttled offshore in 1946. |

Santa Elisa | Torpedoed by two E-boats; afire, abandoned, sunk by direct hits from a dive-bombing Junkers Ju 88. |

Almeria Lykes | Torpedoed by an E-boat, down by the bows; American crew took to lifeboats, refused to reboard; ship was assumed to have sunk. |

Waimarama | Two thousand–plus tons of aviation fuel ignited by four bombs from a Ju 88, quickly sunk; all but about twenty men burned to death in the inferno. |

Deucalion | Holed by a near miss, later torpedoed and set afire by a phantom bomber in a dead-stick dive; abandoned, survivors boarded a destroyer, which left the ship in flames. |

Empire Hope | Three direct hits and many near misses from an attack of Ju 88s, afire, abandoned, scuttled by a torpedo from the destroyer |

Clan Ferguson | Torpedoed by a bomber; up in ferocious flames and down in seven minutes. |

Glenorchy | Torpedoed by an E-boat in the middle of the night; flooding, abandoned except by the captain; sunk in the morning by an explosion aboard, believed to be the captain scuttling her and going down with his ship. |

Wairangi | Torpedoed by an E-boat; flooding, abandoned, presumed to have sunk. |

Dorset | Ahead of the convoy, within sight of Malta, turned back and rejoined convoy; attacked by fourteen Stukas; afire, abandoned, attacked by Ju 88s; direct hit, more fire, sunk by a torpedo from U-73. |

Port Chalmers | Turned back toward Gibraltar; chased by a destroyer and ordered to rejoin the convoy; arrived in Malta undamaged. |

Melbourne Star | Arrived in Malta charred after being caught in the flames of |

Rochester Castle | Damaged by an E-boat torpedo; bombed; fire in the hold carrying ammunition, extinguished; arrived in Malta. |

Brisbane Star | Holed in the bows by a torpedo dropped from a Heinkel He 111; arrived in Malta after limping along the coast of Africa. |

F

OUR

A

IRCRAFT

C

ARRIERS

Indomitable | Attacked by a hundred bombers; three direct hits and many near misses; fifty men killed; returned to Gibraltar, listing and in flames. |

Eagle | Sunk in eight minutes by three torpedoes from U-73; 231 men killed. |

Furious | Flew off thirty-eight Spitfires to Malta; returned to Gibraltar. |

Victorious | Returned to Gibraltar with Force Z. |

T

WO

B

ATTLESHIPS

Nelson | Flagship of Admiral Syfret; returned to Gibraltar with Force Z. |

Rodney | Returned to Gibraltar with Force Z. |

S

EVEN

C

RUISERS

Nigeria | Torpedoed by Italian submarine |

Cairo | Stern blown off by two torpedoes from the same salvo by |

Kenya | Damaged by an E-boat torpedo; returned to Gibraltar with Force X. |

Manchester | Disabled by two torpedoes from two E-boats; fifteen men steamed to death; abandoned; scuttled with depth charges; her captain court-martialed. |

Phoebe | Returned to Gibraltar with Force Z. |

Sirius | Returned to Gibraltar with Force Z. |

Charybdis | Returned to Gibraltar with Force X after being sent forward from Force Z. |

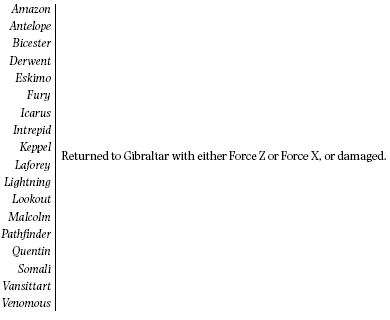

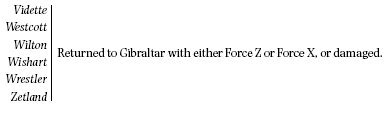

T

HIRTY

-T

WO

D

ESTROYERS

Ashanti | Flagship of Admiral Burrough after cruiser |

Ledbury | Towed |

Penn | Towed |

Bramham | Towed |

Foresight | Disabled by dive-bombers; scuttled by depth charges from destroyer |

Tartar | Towed |

Wolverine | Rammed and sank submarine; returned to Gibraltar. |

Ithuriel | Rammed and sank submarine; returned to Gibraltar. |

Plus a fifth aircraft carrier for exercises, as well as oilers, corvettes, minesweepers, motor launches, tugboats, and nine submarines on patrol.

SOURCE NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS •••

PART I

FATE IN THE CONVERGENCE

The seed of

At All Costs

was sown in 1963, when a small boy in a dark theater in London watched in awe as Stukas dived straight down from the sky at ships of the Operation Pedestal convoy, in battle footage used in the movie

The Malta Story.

Thirty years later, living in New York, he learned that two American merchant mariners and a U.S. tanker had played the pivotal role. It took him another decade to put it all together to bring their story to these pages, and more. The boy was Peter Riva, and in 2003, together with Random House editor Bob Loomis, he and I began working on

At All Costs.

In the spring of 2004 I traveled to Malta and spent seven days with Jan Larsen, the three-year-old boy in this book. We explored the island and dug for its history, in particular during the siege of 1940–43. We met Simon Cusens, whose efforts to track down veterans for the Operation Pedestal reunions in 1992 and 2002 have brought closure to those men, along with some good times over grog. Cusens opened his library to me, as well as some pages of his painstakingly acquired address book, cooperation that got the research off to a rolling start.

All the material accumulated during more than two years of researching and writing, including some forty hours of recorded interviews with the convoy’s veterans, will be contributed to the Operation Pedestal museum that Cusens plans to build on Malta.

The three volumes of

Malta at War,

coffee-table books edited by John Mizzi (who was a boy during the siege) and Mark Anthony Vella, provided insight, illumination, and details in Chapter 1 and throughout the book. They include hundreds of black-and-white photos, articles, and items written in and about Malta during the war years, many of them from

The Times

of Malta daily newspaper. Their publication is a priceless contribution to world history; nowhere else can such a comprehensive picture of Malta during that period be found.

Quotes in the first chapter and subsequent comments by Admiral Cunningham come from his 674–page autobiography,

A Sailor’s Odyssey,

which was one of the two hundred books that squeezed all others out of my office for those two years, including seventy-eight books from the Multnomah County Library in Portland, Oregon, and another seventy-one that were purchased—often used, because they were long out of print. The analysis and opinions of Admiral Weichold, commander in chief of the German Navy in the Mediterranean, appear in an essay he wrote at the direction of the Allies while awaiting trial for war crimes at Nuremberg. Winston Churchill’s quotes are from various writings and speeches, most notably the fourth volume of his World War II memoirs,

The Hinge of Fate.

Governor-General William Dobbie’s quote is from an obscure softbound book he wrote after the war,

A Very Present Help: A Tribute to the Faithfulness of God,

which reveals his religious fanaticism that led to his replacement by Churchill. More but not all Dobbie quotes come from this book.

In Chapter 2,

The Great Influenza

by John Barry contained the information on the flu pandemic of 1918. At Minda Larsen’s home in New Jersey, I began a series of interviews and a friendship with her, amazed by the way she frequently sprang up from a chair in the living room to answer the phone in the kitchen and by how she enjoyed being outside in the cold winter air. Minda emptied the file cabinet containing records of her flight from Nazi-occupied Norway, as well as those of the career of her husband, Fred, including the folder he had labeled “Bad.” He never talked about bad things, so the folder was thin, although it might easily have been substantial. He was a quiet, positive man.

Some information in Chapter 3 came from the book

Operation Drumbeat,

a remarkable event about which relatively little has been written, save this definitive work by Michael Gannon. Other details came from

Hitler’s U-Boat War,

a Random House book researched for nearly a decade by its author, Clay Blair.

Frank Dooley, currently serving his second term as president of the American Merchant Marine Veterans and a shipmate of Fred Larsen in 1959, helped to explain the story of the collision between the

Santa Elisa

and

San Jose

and cleared up many other technical mysteries. Frank introduced me to Toni Horodysky, whose Web site www.usmm.org is a comprehensive reference about the American Merchant Marine at war. Toni’s research ability and initiative cracked open the door to more Internet discoveries. Toni also read the manuscript to catch technical errors, for which I’m especially grateful.

Visits to the New York Public Library turned up microfilm clips from

The New York Times

pertaining to both Operation Drumbeat and the

Santa Elisa/San Jose

collision, while Grace Line documents and some merchant ship records were found at the National Maritime Museum Library in San Francisco, by Bill Kooiman, another ex-mariner who sailed with Grace Line and author of

The Grace Ships, 1869–1969.

And Miriam Devine at the tiny Amenia, New York, library found some books that even the NYPL didn’t have. Miriam was a very young girl in Malta during the siege; more than the bombs, she remembers the hunger.

Theodore Roosevelt Thomson appears in Chapter 3. His daughter, Peg Thomson-Mann, born on the day the

Santa Elisa

was sunk, mailed me a gold mine, a nineteen-page report full of ship’s details, written by her father after the fire. Later quotes come from a 1943 article in

The New Yorker

written by a young Brendan Gill, a wordsmith even then; Gill apparently chose Thomson because the master was only thirty-three. More personal information about Thomson and Fred Larsen was provided by Captain Warren Leback, a Grace Line master for many years and U.S. Maritime Administrator in the Bush, Sr., administration.

Much of the dialogue that takes place on the

Santa Elisa,

and details such as the keg of Jamaican rum kept in Captain Thomson’s head, came from an unpublished manuscript, “Swans in the Maelstrom,” written by the ship’s purser, John Follansbee, who was Larsen’s close friend and who died in 2002. After much searching, I located his son John, who provided the only existing copy of this memoir, as well as a rare copy of a spiral-bound, self-published work by Ensign Gerhart Suppiger, titled

The Malta Convoy.

The descriptions of Suppiger’s thoughts and actions come from this work.

I spoke on the phone to Peter Forcanser, the junior engineer on the

Santa Elise,

who calls Larsen a “square-head,” and has sharper things to say about Ensign Suppiger. “I know them like it was yesterday,” he said. “I think of that ship a hell of a lot. I know how lucky I was.”

Larsen’s sextant hangs on the office wall of his engineer grandson, Scott Larsen, who contributed the sextant story as well as more insight into the character of his grandfather.

That summer, I spent a steamy five days in Augusta and Waynesboro, Georgia, getting to know the Dales family. Marjorie Dales, Lonnie’s widow, covered her kitchen table with five towering scrapbooks and spent the next two days answering my questions with unwavering patience and grace. It’s easy to see why Lonnie left the sea for her.

PART II

THE SECOND GREAT SIEGE

On Malta, Jan Larsen and I spent time with Louis Henwood, a veteran of the Royal Navy and merchant navy, and former mayor of the city of Senglea. Mr. Henwood is also a diver and believes he knows where the

Ohio

lies. His Web site, www.louishenwood.com, has more information about Malta than any other, and some of it appears in Chapters 6 and 7.

Jan and I saw as much as we could in one week. We stood on the bastions surrounding Fort St. Elmo in Valletta, where thousands of Maltese had cheered and cried when the

Ohio

came in and where the cannons of the Knights of St. John had fired the Turks’ chopped-off heads across the harbor. We sidled into the dank caves around the docks, where families had lived during the war. We walked around the towers and pillboxes at the edge of cliffs over the sea and through a cemetery with the tombstones of too many children, as well as those of Axis airmen shot down over Malta. We gazed in silence at the prehistoric Tarxien Temples. We spent an afternoon at St. John’s Cathedral, raided by Napoleon, and were chilled by an all-too-real display deep in the caves under the cathedral, where Maltese had been tortured during the Inquisition.

We took a bus to the ancient walled city of Mdina, where off-duty RAF pilots and Maltese farmers had watched dogfights in the sky. We visited the National War Museum and spent an afternoon at Takali airfield, now the site of the Malta Aviation Museum, where we examined a restoration of one of the original Gladstone Gladiator biplanes. We spent a fascinating few hours with Ray Polidano, director of the museum foundation, who worked in a hangar in back; he walked us around and told stories of the men and planes at Takali.

Most of the information on the Malta Gladiators, both the men and the machines, came from this visit and the book

Faith, Hope and Charity

by Kenneth Poolman, an old paperback found, like so many, after searching the Web sites of rare-book sellers. More material in Part II came from Michael Galea’s

Malta: Diary of a War

and

Raiders Passed,

by Charles B. Grech, one of the Maltese boys who collected shrapnel like arrowheads during the siege.

Chapters 8, 9, and 10 were by far the most challenging to write, because they span two years, and there are three or four more unwritten books in there, in particular regarding the bombing of the

Illustrious,

Admiral Cunningham’s biggest (and maybe only) blunder, which historians have yet to address.

In using so many sources and voices, it was difficult to reconcile the differences and contradictions, which demanded choices about credibility and probability. These chapters include quotes from autobiographies, memoirs, or diaries by Admirals Cunningham and Weichold and General Dobbie; Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander in chief of the Luftwaffe; Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the legendary leader of the Afrika Korps; Admiral Erich Raeder, commander in chief of the German Navy; Admiral Karl Dönitz, the U-boat commander; Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and minister of foreign affairs; Air Marshal Sir Hugh Lloyd, the RAF’s commanding officer on Malta; Admiral G.W.G. “Shrimp” Simpson, commander of Malta’s 10th Submarine Flotilla; General Hastings “Pug” Ismay, Churchill’s chief of staff; General Alan Brooke (later Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke), chief of the Imperial General Staff and Churchill’s closest military adviser; Sir Charles Wilson, Churchill’s personal physician, who wrote his memoir as Lord Moran; Elizabeth Layton Nel, Churchill’s young and resolute Canadian secretary; and of course Churchill himself.

There were also biographical books in the pile, for example of Admiral Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty, and of the 10th Submarine Flotilla. And

The Italian Navy in World War II

by Marc’Antonio Bragadin, the official Italian history, along with

The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1940–1943

by Jack Greene and Alessandro Massignani—a British and an Italian historian, allies in accuracy. Another invaluable reference was Captain Arthur R. Moore’s

A Careless Word…A Needless Sinking,

a heavy encyclopedia of all the American merchant ships lost in World War II.

Among five memoirs by fighter pilots, two were particularly evocative, and they found their way into Part II. Insight and beauty float off the pages of

Tattered Battlements

by Tim Johnston, DSC, and

War in a Stringbag

is unique because its author, Charles Lamb, DSO, DSC, bombed Taranto and lived to tell about it and witnessed the brutal bombing of the

Illustrious

from the air as Stukas swarmed around his shabby biplane and paid him no mind.

The statement in Chapter 9 from the Luftwaffe pilot who flew into the Royal Malta Artillery box barrage and dropped his bombs prematurely was taken from a letter he wrote after the war to

The Times

of Malta

.

With all the aircraft action in Part II, technical books on the planes, such as

Aircraft of WWII

and

Jane’s Fighters of World War II

were used. But my favorite was

Wings of the Luftwaffe

by Captain Eric Brown, the RAF’s chief test pilot, who flew captured German planes and wrote about them as if he were doing road tests for a British car magazine.

There were many discrepancies in the reports of the number of Axis aircraft involved in the various attacks. But the books

Malta: The Hurricane Years, 1940–41

and

Malta: The Spitfire Year, 1942

by Christopher Shores and Brian Cull with Nicola Malizia solved most of them. These reporters worked more than ten years to acquire the accurate documents.

PART III

ALLIES

From Malta I flew to London and spent two weeks researching in England, beginning at the Imperial War Museum and the National Archives, where I pored over documents: books, films, audiotapes, cables, and especially Letters of Proceeding, the action reports written by Royal Navy officers and masters of merchant ships. The plot thickened. With each report, questions arose that added two or three more reports to the list. There was far too much information at the National Archives to note or even photocopy during four days there, so I recruited a researcher, Tim Hughes, who caught the detective bug and continued to dig for documents at my request. Tim found pieces of the puzzle into the final chapter.

Many of the documents we found and examined were declassified by the British government only in 2002. If the reader wonders how the full story of such a significant World War II battle could have been untold for so long, this is part of the answer; also the fact that Tim Hughes looked in places historians had apparently missed, in response to my wondering what was under every rock and my being struck by the heretofore undrawn connections between events.