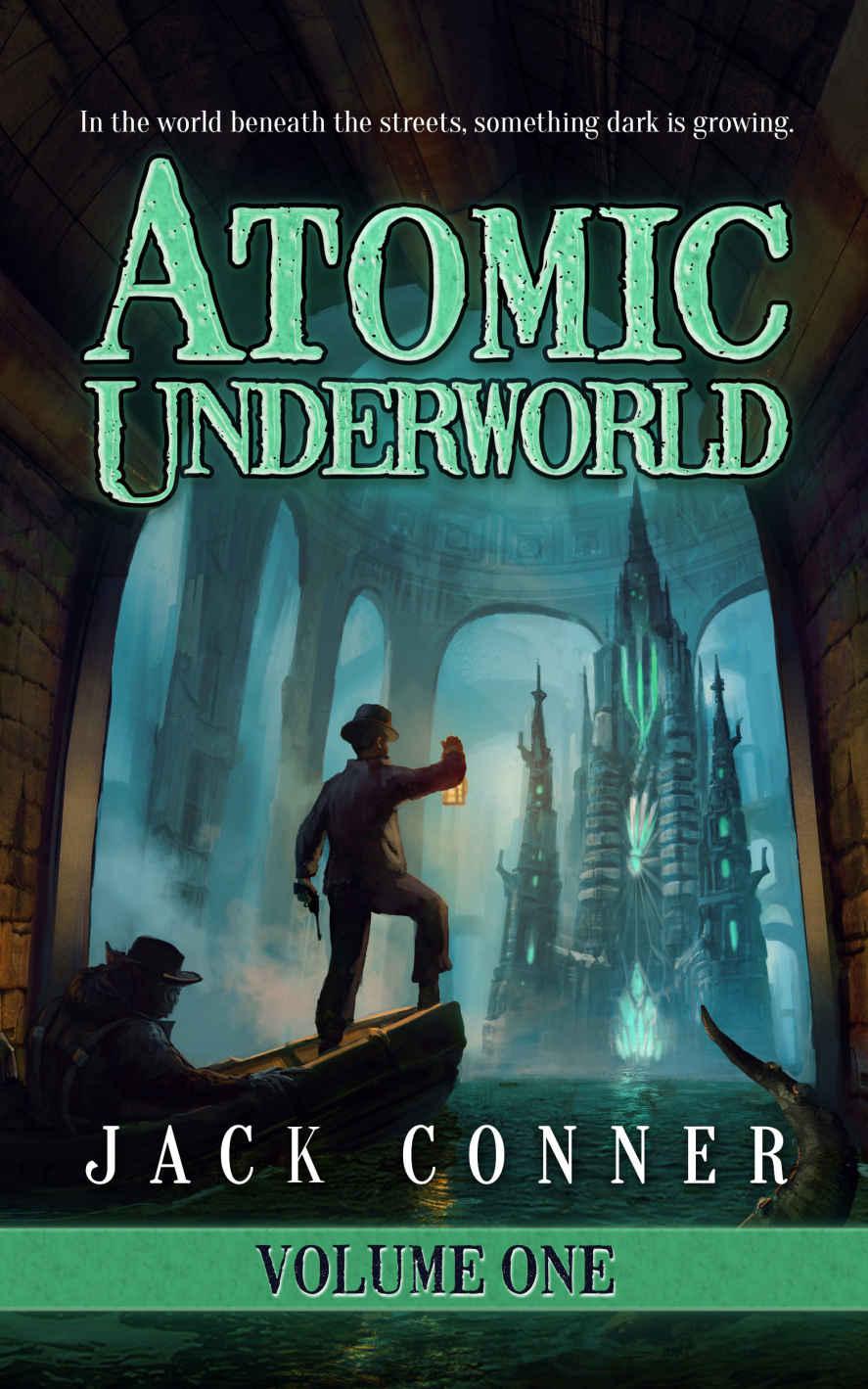

Atomic Underworld: Part One

Read Atomic Underworld: Part One Online

Authors: Jack Conner

ATOMIC UNDERWORLD:

by Jack Conner

Copyright 2016

All rights reserved

Cover image used with permission

FREE GIFT:

To claim your FREE Jack Conner Starter Library, which

includes FOUR FREE NOVELS, sign up for my newsletter here:

http://jackconnerbooks.com/newsletter/

The

three moons shone high over the Atomic Sea the night Frankie found him.

Tavlin

was playing cards at Savver’s, a tavern situated on a rooftop garden perched atop

a tall, gargoyle-encrusted building of weathered stone. Lightning flickered up

from the harbor in a thousand electric tongues, and somewhere a gas pocket

exploded out over the waters, but Tavlin was too far away to hear the thunder

or the boom, and he was winning besides.

“Match

and raise,” he said, flicking in several chips.

“You’re

cheating,” said Verigga, a hulking woman with a scar across one eye and half

her face.

The

others at the table quieted. They were a rough lot, hard and tattooed and grim.

Smoke wreathed up from their cigarettes and cigars, but that was the only

movement at the table.

“I’m

in a good mood, so I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that,” Tavlin said.

“You’re

a cheat,” Verigga said. Her scarred eye was white, and milky clouds drifted

across the pupil. “I been

studyin

’ you. I admit I

don’t know how you’re doin’ it, but I know you are.”

Tavlin

relaxed.

She can’t prove anything

.

“Apologize.”

“Do

what?”

“Else

I’ll have to consider your accusation as calling me out.”

“I’m

not apologizing.”

With

exaggerated calmness, he stuffed and lit his pipe. The tobacco was an

alchemical concoction, and the smoke that curled up from the bowl bore a

greenish tint.

“I

choose knives,” he said, then waited.

Please

work.

Verigga

paused, as if his choice had actually made her rethink her accusation, then

made a decision. She climbed to her feet, knocking her chair to the floor (which

was more dramatic than Tavlin thought strictly necessary), and stabbed a finger

at him. “That man’s a cheat or I’m a beauty queen, there ain’t no two ways

about it.”

Tavlin

felt himself grow cold. His reputation wasn’t good enough to survive such

allegations. He’d already been banned from multiple gambling houses, which is

why he shivered on a rooftop garden two hours past midnight with this lot.

Slowly,

making a show of it, he mounted to his own feet, placed his pipe on the table,

and glared at Verigga. There was still a chance to scare her off.

“Are

you calling me out?” he said.

“I

damn well am.”

“Knives,

then.” His reputation in knives was something he had paid very well for.

Too

well, as it turned out.

She

spat. “Do I look like I fear knives, Tavlin Two-Bit—or anything else?”

“Maybe

a shower.”

Apparently

that was the wrong thing to say. She reached to her waist and ripped out the

largest knife he’d ever seen. It should have been wielded by some knight of

ages past against some lumbering reptile or monstrous bug.

“Shall

we take this somewhere else?” she said. “I hate to get blood on the money.”

Tavlin

glanced to the others. They traded looks, but none volunteered to help. Likely

they wondered if Verigga might be right.

A

dark figure appeared behind the woman. A short sharp length of metal glimmered

at her throat. A voice croaked, “Leave now or go home shorter.”

Verigga

seemed about to move against her assailant, but the knife twitched, and blood

leaked down her neck.

With

a snarl, she shoved her own weapon back into its sheath. The blade at her

throat retracted. She spun about, but the other knife was still out, and it

danced back and forth as if taunting her. Its wielder stood in shadow.

“This

isn’t over,” she said to Tavlin, then gathered up her money and stormed off.

Tavlin

wiped sweat from his forehead. “To whom do I owe the thanks?—not that I needed

the help, mind.”

Out

of the shadow stepped a squat figure, more toad than man, with dark green skin,

bulbous neck and torso, and jutting, wide-lipped batrachian mouth. He was

obviously infected. Mutated. Many of the infected lived here in Hissig,

constant reminders of the nearness of the Atomic Sea. What was more, Tavlin

recognized him.

“Frankie.”

Frankie’s

webbed hands moved, and the knife disappeared. His eyes stared at Tavlin,

unblinking. “We need to talk.”

Tavlin

cashed in his chips—this was not a formal casino, but there was an independent

bookie—and followed Frankie into a shadowed corner of the tavern garden.

Midnight blooms nodded all around, lacing the night with a lavender fragrance,

and from somewhere drifted the sounds of jazzy music, crackly and fitful, as if

emitted from an old gramophone, not one of the newer record players. It echoed

strangely through the misty spaces between this building and the next. The

drinking and gambling continued, but here Tavlin and Frankie had a sphere of

privacy.

“What’s

this about?” Tavlin asked. If he hurried, he could get back to the game without

missing more than a hand.

“There’s

trouble.”

“There

always is.”

“This

ain’t like most trouble.”

Tavlin

felt a sinking sensation. “I’m afraid to ask, but you still work for Boss

Vassas, don’t you?” When Frankie said nothing, just stood there stone-faced,

blinking his frog eyes slowly, Tavlin grimaced. “This trouble ... it wouldn’t

have anything to do with him, would it?”

“Who

else?”

“Shit.

Listen, Frankie, I want no part of this. I don’t even know what this is and I

want no part of it.” He started to leave.

“I’m

afraid I ain’t askin’.”

Two

large figures materialized from the darkness. They were infected, too, huge and

piscine. Their fish scales glistened wetly in the moonlight.

“

Sonofabitch

.” Tavlin glared. “Alright, what’s this about?”

“Now

you’re talkin’. And it’s better to show you. Come’n.”

Frankie

set off for the stairs. Reluctantly, Tavlin followed, knowing it would be

better to miss the game than to offend Boss Vassas. The two goons trailed him.

The group reached the stairs, took them to the next level down, then a fire

escape. This led to a gravel-lined surface, and from here they took a bridge of

bolted metal pipes over to another rooftop. Wind howled about them, bringing

with it drops of moisture and flapping Tavlin’s coat out behind him. It was a

cold, wet night, but he navigated the aerial highway with practiced ease. To

the west, lightning flickered up from the seething, toxic water of the Atomic

Sea, and Tavlin tried not to think about the monstrous things that lived in it.

One of them—or something derived from them, anyway—slithered up a wall across

the way: a fur-covered octopus, or drypuss, searching for a rat to eat, or

maybe a family pet or infant if it could get in through a window.

“You

shouldn’t have helped me,” Tavlin said. “What if word spreads that I can’t take

care of myself? Which I could have, by the way.”

“Yeah,”

Frankie said. “She looked like a pushover.”

“Even

so.”

Frankie

shrugged. “You seemed like you could use the help, and I need you alive. Ain’t

my job to look after your career, or whatever the hell it is. Just what are you

doing up here, anyway? You had a life down below.”

Tavlin

scowled at Frankie’s wattled neck. “I have a life here.”

“Yeah.

Some life.

Livin

’ outta rats’ dens, cheatin’ lowlifes

at crummy bars. Why

d’ya

cheat, anyway? You’re pretty

good on your own.”

“I

don’t cheat.”

“Listen,

I saw you. That cyclops may not’ve seen the cards up your sleeve, but I did.”

Tavlin

said nothing. On one hand, he was relieved that Frankie had helped him. If he’d

won the duel against Verigga and had killed her, he would have had to drink

himself to sleep for many nights afterwards. It would have been different if

she’d been wrong, but to stick someone for catching you actually cheating

seemed like bad form. And of course, he might not have won.

“Whatever,”

Frankie went on. “You’re goin’ below now.”

Tavlin

repressed a shudder. “Must we?”

“Yes.”

“And

you won’t tell me why?”

“You’ll

find out soon enough.”

“As

long as it’s not about some debt I owe ... It’s not, is it?”

Frankie’s

grunt was his only answer.

They

passed down through the city, the crowded, ancient metropolis of Hissig,

capital of Ghenisa. Fog curled through the streets, and moisture beaded the smoked

glass above. Thick domes fashioned of stone and massively encrusted buildings

loomed in the darkness, moisture dripping from the horns and teeth of gargoyles

and serpentine dragons, and from the breasts of six-armed goddesses and other

creatures of myth. Great stone buildings and monuments hunched like sentinels,

interspersed with occasional skyscrapers. The older buildings showed countless

pocks and scars from war, most notably the Revolution fifty years ago and the dark

times of the War of the Severance hundreds of years before that, but there was

still some signs of the debaucheries and madness of the Withdraw nearly a

thousand years ago.

Tavlin

passed a window through which a radio hissed and crackled: “ ... which the Archchancellor

of Octung denies. He continues to claim the expansion and development of the

Octunggen military is for defensive purposes only. Meanwhile he and his party

members have been giving stirring speeches to packed crowds in Lusterqal and

elsewhere, and there is much activity around the temples to the Collossum.

Reporters are being shut out and even evicted from the country ...”

“Damned

Octung,” Frankie snorted as they scrambled down another fire escape. “They’ll

make their war, you can be sure of that.”

Tavlin

knew Frankie was probably right. And Octung was only half a continent away from

Ghenisa. When the war started, Ghenisa would be hard pressed. Already refugees

seeking asylum or a boat out were beginning to arrive in Hissig.

“We’ll

hold,” Tavlin said with more confidence than he felt.

They

reached street level and passed through the swirling, acrid fog until they

arrived at a manhole cover. Tavlin watched skeptically as the two goons jimmied

it up. The manhole cover groaned as metal grated on asphalt, and the big men

rolled it away. Revealed in its place was a dark, gaping pit. A fetid reek

curled out. As Tavlin stared at the darkness, a wave of dread seemed to settle

in his gut.

“I

don’t like this.”

“You

don’t have to,” Frankie said. “Just get your head out of your ass and come on.”

Frankie

slipped into the hole, having to squeeze his slimy bulk through, and descended

via the rungs bolted into the sewer wall. The goons prodded Tavlin toward the

hole, and for a moment he thought of running—it was starting to feel like a

good idea—but he knew if he ran he would have to keep on running. With a sigh,

he followed Frankie down. Instantly the stink of the sewer wrapped him in its

embrace, and he felt his gorge rise. He tried to resurrect his old immunity to

the reek, but it didn’t come.

He

lit on a concrete surface, and darkness surrounded him—almost. The large men

had replaced the manhole cover, but a thin slice of light came from overhead,

and it glimmered off the slowly-moving river that ran by the walkway. Tavlin

tried not to look at it for long, and its stench made him want to retch. His

eyes burned.

“I

better get paid for this,” he said.

“That’s

up to you and the boss.”

That

gave Tavlin some hope. He wasn’t being taken to his death, then. At least not

directly. And profit was always something to look forward to.

The

rough men lit flashlights, and the group set off. They passed down this hall,

then another. The walls were composed of rough-hewn stone blocks, scored by

time and marked by graffiti, some of which looked quite old, written in

languages Tavlin didn’t even recognize. He knew the sewer system was a

composite thing, built over centuries by the different nations that had

occupied Hissig. Much of it had been carved out of the earth thousands of years

ago, back when the Empire of L’oh had ruled the continent. He thought the

section he was walking through now was probably built by them. But some of it

was built in even

older

times, by

civilizations thriving before humans had walked the planet.

Something

splashed in the fetid river, and one of the goons shone a flashlight on it.

Nothing. Then: a white shape breached the surface, slipped back under. It had

gills and whiskers. “Wish I’d brought my net,” said the man.

Tavlin

tried to resist curling his lip. The sewers merged with underground tunnels

that ran to the Atomic Sea, and the waters had become mixed with the sea’s

strange energies. Now an entire ecosystem lived down here, but it was an

ecosystem that Tavlin would prefer not to dwell on.

They

walked for a ways, sometimes ducking down narrow, slimy tunnels, sometimes

crossing bridges over the river—bridges that seemed formed by the secretions of

some awful insect—sometimes descending stairs beside ancient locks, coming into

a lower part of the sewer, and finally the tunnel they walked through spilled

out into a great chamber, one of the huge cisterns where someone could shout at

one end and not hear his echo for minutes afterward, if at all. Here the

ceiling arched to a dome overhead, so high up Tavlin couldn’t see it, and the

river became a lake. In the center of the lake lights blazed and shapes shifted

and swayed to unknown rhythms. Tavlin saw boats lashed together, ancient piers

and docks, buildings rising from the chaos. Sounds drifted across the waters.

Tavlin heard music.