Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (29 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

As these stuttering moves unfolded, Kutuzov, although nominally commander of the Allied army, saw his authority increasingly marginalized. Langeron commented that he was ‘commander-in-chief of the army, but commanded nothing’.

15

On one occasion, when Kutuzov asked the tsar for instructions regarding the order of march, Alexander responded, ‘That does not concern you.’ All direction now came from Weyrother, encouraging the tsar’s young and opinionated followers to ridicule the aged general behind his back, referring to him as ‘General Dawdler’. Yet Kutuzov was not alone in receiving such insults. Langeron adds that these same aides treated the Austrian generals and officers with similar contempt, with ‘uncalled for jokes about the way they spoke and even on the uniforms of their allies. Even Kaiser Francis was not safe from these indecencies.’

16

Langeron recorded the frustrations of a typical day during the advance towards the French:

‘In the morning each general had to send to the four other columns to seek the regiments which were to compose his, and which, sometimes, were obliged moreover to march [5 or more miles] to reach him … It was always ten or eleven o’clock before we could assemble. Often the columns cut across each other … We arrived late, we scattered to seek food, we plundered the villages and disorder was at its height.’

17

While Friant’s division of Davout’s corps marched 45 miles on 30 November, the Austro-Russian army managed to struggle across bad cross-

country roads for 10 miles to take up a position between Niemschan, running through Hodiegitz, to Herspitz, about 3 miles east of Austerlitz, which Kienmayer continued to occupy. Bagration, with the Army Advance Guard, remained on the Olmütz–Brünn road close to the Posoritz post house, with outposts pushed forward to Holubitz and Krug, covering the junction where the road to Austerlitz branched off to the south. The Imperial Guard was furthest back at Butschowitz, around 4 miles to the rear.

During the day French outposts occupied the high ground of the Pratzen Plateau and had a perfect view of the leaden movements of the Allies. Napoleon also took the opportunity to observe the slow advance, relieved by its laboured approach, for all the time Bernadotte and Davout were drawing closer to the area he had chosen for battle.

This constant flow of soldiers marching across the rolling Moravian hills between Brünn and Olmütz did not take place in a landscape emptied of people. Of course some did abandon their homes to seek safety beyond the reach of the marauding armies, but others remained and saw their property and livelihood destroyed by friend and foe alike. Close to the great shallow lake at Satschan, in the villages of Menitz, Satschan and Telnitz, many villagers chose to stay. A local priest recorded their traumatic experiences:

‘On 18 November, the entire Austrian army … led by Kienmayer, marched through Menitz and the rear sections of the army stayed in Menitz, Satschan and Telnitz for the night. This evening marked the beginning of our sorrows. Because our homes and barns were unable to house the army, they settled themselves into the streets and lit more than a hundred fires very close to the buildings, creating a bright day in the dark of night…It looked as though Menitz itself were engulfed in flames … The entire sky was aglow with a deep red colour. On this night alone the villagers lost a large part of their wood supply, straw, fences, gates and doors, used by the soldiers to feed their unquenchable fires. All through the night the only sounds heard were the breaking of the gates, doors and fences, and the cries of the anxious citizens.’

18

On the following day the Austrians marched on towards Jirzikowitz, leaving a small hussar rearguard, but at 3.00pm these too rode off when the leading elements of the French army came into view:

‘We witnessed the last Austrian soldiers disappearing behind Telnitz and immediately following them we could hear thunderous tramping and the distinct clatter of weapons and army songs of the French. Panicked citizens, who had never seen an enemy in their lives, ran to

and fro, wringing their hands in despair. In their anxiety, Menitz’ citizens set forth toward the enemy in order to meet them and appeal to their enemy’s compassion and grace … In the meantime, the French forged onward from Menitz to Telnitz without interruption. When the enemy finally arrived at the fields near the edge of Telnitz they suddenly halted, stacked their muskets, and rushed, en masse, into Telnitz, Menitz and Satschan, charging into buildings and stealing anything they could lay their hands on: food, clothes, beds, furniture (tables, chairs), and so on, and used all of these acquired possessions to feed their fires. This violence continued all throughout the night. You could see nothing but the constant comings and goings of the enemy with their booty.’

19

On the morning of 20 November the French left the villages and marched off towards Austerlitz, but for three days the villagers watched a constant stream of soldiers marching through Menitz and Telnitz. Then on 24 November a French regiment arrived and was billeted on Satschan and Menitz, staying for five days and increasing the suffering:

‘It is not possible to sufficiently describe the horrors the inhabitants endured in those five days. They hardly had any basic material left with which to survive themselves, but were still expected to supply the soldiers with food and horse feed; any non-compliance would have led to the people being killed or burned out of their homes and towns. However, fortunately the local pond was full of fish and so they could comfortably supply the enemy with food. Day after day cattle were slaughtered, and as soon as they were butchered, the next immediate thought was where to find more cattle and food for the following day.’

20

Then, during the night of 29–30 November, a French drummer beat the assembly and ‘in five minutes the entire regiment disappeared’. They returned after an hour, but thirty minutes later:

‘another commotion could be heard. From the chaos and agitated discussions of the officers, one could judge that something big was going to happen. Soldiers, in much disarray, packed their kits hurriedly, and with pale faces informed the inhabitants, “The Russians are coming.”’

21

And with these worrying words the French departed. In fact a short period of peace descended on the troubled villagers. A detachment of Austrian dragoons and Russian Cossacks rode into Satschan, raising the hopes of salvation for the inhabitants, but these were swiftly dashed:

‘We abandoned all our previous sorrows and anxieties as soon as we saw the glistening white uniforms and heard our mother tongue spoken by an officer. We hoped that we would be delivered from the horror of our enemies. But the regiment galloped away again after an officer questioned us about the distance and strength of the enemy, about which we were not able to answer very accurately.’

22

For the villagers, the horror of their situation would soon return.

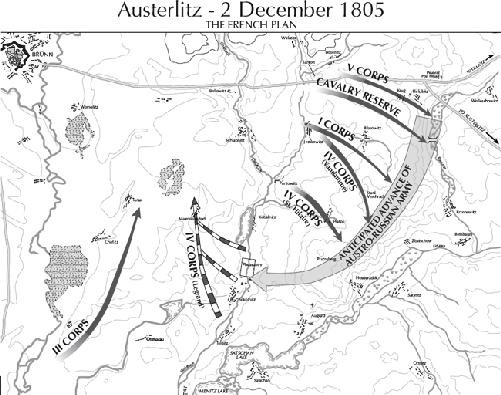

While the Allies continued to edge forward slowly, Napoleon took the opportunity to tour the area on which he intended to fight once more. Riding with his marshals, Napoleon openly discussed his plans for the coming battle. He had cavalry outposts on the Pratzen Plateau and he could easily have occupied it with his whole army. From this strong position, he explained to them, he could defeat the Allies but considered that it would result in ‘just an ordinary battle’. An ordinary battle meant that once he gained the upper hand the Allies would fall back, as they had done so many times before, forcing him to follow deeper into Moravia or more likely towards Hungary, where Archduke Charles could add massive reinforcements to his opponent’s army. Napoleon needed a climactic battle, one that would bring the campaign to a sudden and final end. He informed his marshals that by giving up this dominant position he hoped to tempt the Allies forward. If they left this high ground to turn his right – for the confused manoeuvring of the Allies suggested this was their strategy – then he intended to draw them on before launching a sudden strike against the plateau to place himself in their rear and on their flanks. For this purpose he intended concentrating the main force of the army close to the Santon. This, he felt sure, would result in a crushing defeat for the Allies, leaving them ‘without hope of recovery’.

23

That evening Napoleon returned to his headquarters, now established on Zuran Hill just over a mile south-west of the Santon, above the village of Schlapanitz. Here he received the news he had been anxiously awaiting. Bernadotte, with I Corps, was encamped outside the gates of Brünn, only 6 miles from the battlefield. Then more good news followed. Marshal Davout arrived, far ahead of his men, but he was able to promise the emperor that the divisions of Friant and Bourcier would be within reach the following day. Napoleon could anticipate an army about 74,000-strong with which to oppose the 78,000 of the Allies, who were gradually drawing closer. Since the Austro-Russian army commenced its march from Olmütz, Napoleon’s strength had increased by just over 40 per cent.

As the two armies settled down for the night, lying only 9 miles apart, it was time for Napoleon to plan his final dispositions for the battle that now appeared inevitable. The eagles of France, Russia and Austria were gathering for the kill.

__________

*

Satschan parish records, later recorded in the local school chronicle.

Chapter 13

‘To Make the Russians Dance’

‘Let us go the emperor replied, I hope

that tomorrow evening things will be better.

And us also, almost all the grenadiers

said, because we are more than

willing to make the Russians dance.’

*

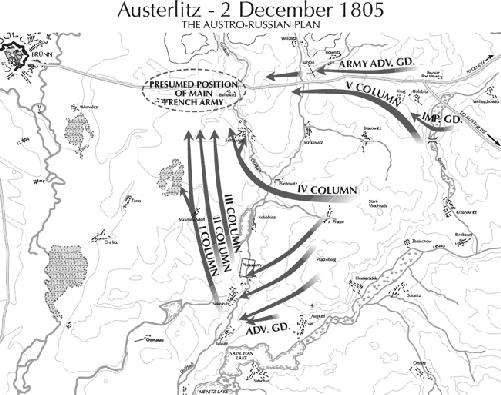

Dawn on the 1 December heralded another cold, damp day. But if Napoleon expected to see the Austro-Russian army advancing towards him as he climbed the Pratzen Plateau, he was to be disappointed. That morning, Allied headquarters circulated orders for further changes in the composition of the attacking columns, and it was not until the early afternoon that they finally began to march towards the plateau. Alexei Ermolov, the Podpolkovnik of a Russian horse artillery battery attached to V Column, watched the columns advance in amazement:

‘The columns were colliding and penetrating each other, from which resulted disorder … The armies broke up and intermixed and it was not easy for them to find their allocated positions in the dark. Columns of infantry, consisting of a large number of regiments, did not have a single person from the cavalry, so there was nothing to help them find out what was going on ahead, or to know where the nearest columns, appointed for assistance, were and what they were doing.’

1

However, not all the Allies spent the entire morning in inactivity. Kienmayer probed south of the Pratzen Plateau with his cavalry, pushing outposts towards Satschan and Menitz, villages bordering the great shallow lake. At 10.00am a cloud of Kienmayer’s Cossacks disturbed a reconnaissance from Menitz by the

French 11ème Chasseur à cheval. After much tentative manoeuvring by both sides, the Cossacks were eventually driven off and the French horsemen in turn retired to their bivouac at the extreme right of the French position.

2

Elsewhere outposts kept up an annoying exchange of fire throughout the morning.

The slow, deliberate movements of the Allied army observed by Napoleon convinced him it would now occupy the Pratzen Plateau as he had hoped. With this high ground secured, he anticipated the Allies forming a line from a position opposite the Santon in the north, running southwards along the plateau, to a point facing the village of Kobelnitz on the Goldbach. Before returning to his camp on the Zuran Hill, Napoleon toured through the army visiting many of his regiments and batteries, encouraging the men, for at last he felt certain that battle would follow the next day.