Away Running (25 page)

Tensions had been running high in Paris’s poor suburbs like Clichy-sous-Bois. Populated largely by immigrants, many from France’s former colonies in North and

sub-Saharan Africa, the townships had become a toxic combination of all the country’s social ills: a decaying urban landscape, pockmarked with overpopulated and poorly maintained high-rise projects; widespread under- and unemployment; inferior education; juvenile delinquency; and crime. In a speech the week before, Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s interior minister (who would be elected president a few years later), had made sweeping and disparaging statements about the projects, describing its hip-hop-identified young residents as “

racaille

.” Commonly translated as “scum,” the word can also mean “vermin.” Sarkozy vowed to “

nettoyer la cité au Kärcher

”—to clean out the high-rise projects with a power hose, the language evoking the work done by an exterminator.

Relations between neighborhood residents and the police quickly deteriorated. Sarkozy assigned the

CRS

—the riot squads, which have a reputation for viciousness—to police these neighborhoods. Frequent and repeated checks of identity documents became commonplace. Residents perceived the

CRS

presence as being intended to intimidate, not to protect.

When the police cars sped up on the group of boys in Clichy-sous-Bois, three of them—Muhittin Altun, seventeen, Zyed Benna, seventeen, and Bouna Traoré, fifteen—panicked. Fearing the aggressive police as much as the eventual wrath of their parents for getting arrested,

they ran. Muhittin, Zyed and Bouna sprinted past the graffiti-covered wall of a cemetery, the police chasing after them. Ignoring the skulls and crossbones, the Danger–High Voltage signs, the boys climbed the concrete wall of the electric substation in an attempt to hide.

The pursuing officers saw them enter the site. One commented, “If they enter the

EDF

compound, they’re as good as dead.” Still, despite recognizing the danger, the police left the scene without attempting to go to the aid of the boys—a violation of French law. They later reported not having pursued them at all.

Not long after, the entire neighborhood went suddenly dark. One of the boys must have misstepped. A blue charge—twenty thousand volts of current—engulfed the three youths. Zyed and Bouna died instantly. Muhittin, his clothes burned into his skin, managed to climb out and stagger back to his high-rise.

News of the deaths sparked violent riots, first in Clichy-sous-Bois and neighboring suburbs, then throughout the entire country. Over the course of the following month, dozens of public buildings were vandalized and burned, and thousands of cars were set ablaze. Five people died. Though three thousand rioters were arrested, no police officers were found guilty of any wrongdoing, not even those who saw the boys enter the substation and fled the scene.

Zyed, Bouna and Muhittin’s tragic story inspired us to write

Away Running

. Though our novel is not those boys’ story, their story has allowed us to explore the promise and the failures of multiculturalism and the accountability we all bear for one another.

Please visit

www.awayrunning.com

for more information and go to our Study Guide for Teachers for strategies and exercises that can help you incorporate the themes of our book into your lesson plans.

Many thanks to Paul Rodeen of Rodeen Literary Management, an old friend who had the vision to imagine this as a work of fiction when we were struggling to write it as nonfiction, and to Sarah Harvey, our editor at Orca, whose sharp eye helped make the narrative work. Thanks also to our former teammates from the Flash de la Courneuve—notably François Leroy, Jacques Tillet, Fabrice Delcourt and François Rouat—and to Frédéric Martin, for giving us access to people who had been involved in the rioting as well as to police officers assigned to those neighborhoods.

The English Department at the University of Illinois provided generous support from the start, and residencies from the Blue Mountain Center, the MacDowell Colony, the Texas Institute of Letters and the Yaddo Foundation gave us the time to get the work done. Profound thanks.

Portions of chapters seven, eight and thirteen appeared previously in different form in the literary journal

Callaloo

(vol. 34 no. 4, November 2011), under the title “Going Places.” The essay that inspired the novel also appeared in

Callaloo

(vol. 32 no. 1, February 2009), under the title “Away, Running: A Look at a Different Paris.”

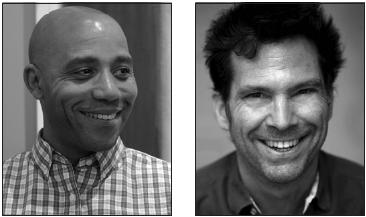

DAVID WRIGHT

and

LUC BOUCHARD

met as teammates playing American football for the Flash of La Courneuve in suburban Paris. David, a writer and teacher of writing, has since returned to Champaign, Illinois, a home base from where he sets out abroad, most recently to Bahia, Brazil, and Benin, West Africa. Luc now lives in Montreal with his partner and his two daughters. Along with

Away Running

, last year he also finished

Bras de Fer

, on the infiltration of organized crime into Quebec's largest construction union. For more information about David, visit

www.davidwrightbooks.com

, and for Luc, visit

www.bouchardluc.com

.