B0041VYHGW EBOK (104 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

As

Rear Window

goes on, the subjectivity of the POV shots intensifies. Becoming more eager to examine the details of his neighbor’s life, Jeff begins to use binoculars and a photographic telephoto lens to magnify his view. By using shots taken with lenses of different focal lengths, Hitchcock shows how each new tool enlarges what Jeff can see

(

6.90

–

6.93

).

Hitchcock’s cutting adheres to spatial continuity rules and exploits their POV possibilities in order to arouse curiosity and suspense.

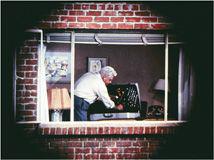

6.90 When Jeff looks through his binoculars …

6.91 … we see a telephoto POV shot of his neighbor.

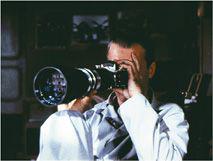

6.92 When he employs a powerful photographic lens …

6.93 … the resulting POV shot enlarges his neighbor’s activities even more.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For more examples of point-of-view editing and an analysis of a scene, see “Three nights of a dreamer,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1457

.

Most continuity-based filmmakers prefer not to cut across the axis of action. They would rather move the actors around the setting and create a new axis. Still, can you ever legitimately cut across an established axis of action? Yes, sometimes. A scene occurring in a doorway, on a staircase, or in other symmetrical settings may occasionally break the line. Sometimes, too, the filmmakers can get across the axis by taking one shot

on the line itself

and using it as a transition. This strategy is rare in dialogue sequences, but it can be seen in chases and outdoor action. By filming on the axis, the filmmaker presents the action as moving directly toward the camera (a

head-on

shot) or away from it (a

tail-on

shot). The climactic chase of

The Road Warrior

offers several examples. As marauding road gangs try to board a fleeing gasoline truck, George Miller uses many head-on and tail-on shots of the vehicles

(

6.94

–

6.98

).

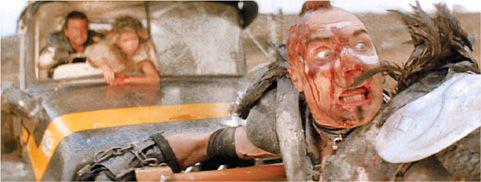

6.94 Near the climax of the chase in

The Road Warrior,

Max is driving left to right along the road …

6.95 … and in later shots he is still driving toward the right. An attacking thug perched on the front of the truck turns and looks off right in horror …

6.96 … realizing that another vehicle, moving right to left, is coming toward them on a collision course.

6.97 Several quick shots facing head-on to the vehicles show the crash …

6.98 … and a long shot shows the truck again, now moving right to left.

“I saw David Lynch and asked him: ‘What’s this about crossing the axis?’ And he burst out laughing and said, ‘That always gets me.’ And I asked if you could do it, and he gave me this startled look and said, ‘Stephen, you can do anything. You’re a director.’ Then he paused and said, ‘But it doesn’t cut together.’”

— Stephen King, novelist, on directing his first film,

Maximum Overdrive

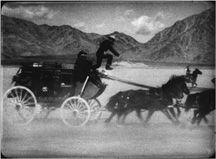

Also, we should note that continuity-based films occasionally violate screen direction without confusing the viewer. This usually occurs when the scene’s action is very well defined. For example, during a chase in John Ford’s

Stagecoach,

there is no ambiguity about the Ringo Kid’s leaping from the coach to the horses

(

6.99

,

6.100

).

We wouldn’t be likely to assume that the coach had turned around suddenly, as in the possible misinterpretation of the shootout scene with the two cowboys (

6.51

).

6.99 In

Stagecoach,

in a long shot where all movement is toward the right, the hero begins leaping from the driver’s seat down onto the horse team …