B0041VYHGW EBOK (143 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Finally, the categorical film can maintain interest by mixing in other kinds of form. While overall the film is organized around its category, it can include small-scale narratives. At one point,

Olympia

singles out one athlete, Glen Morris, and follows him through the stages of his event, because he was an unknown athlete who unexpectedly won the decathlon. Similarly, a filmmaker might take a stance on his or her subject and try to make an ideological point about it, thus injecting a bit of rhetorical form into the film. We’ll see that Les Blank hints that treating gap-teeth as a flaw reflects a society’s bias about what constitutes beauty.

“The whole history of movie making has been to portray extraordinary things, and no one has felt that much confidence in looking at life itself and finding the extraordinary in the ordinary.”

— Albert Maysles, documentary filmmaker

Categorical form is simple in principle, but filmmakers can use it to create complex and interesting films, as

Gap-Toothed Women

demonstrates.

Gap-Toothed Women

Les Blank has been making modest, personal documentary films since the 1960s. These are often observations of a single unusual subject as seen by a variety of people, as with his

Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers.

Several of Blank’s films use categorical organization in original ways that demonstrate how entertaining and thought-provoking this simple approach to form can be.

Gap-Toothed Women

was conceived, directed, and filmed by Blank, in collaboration with Maureen Gosling (editor), Chris Simon (associate producer), and Susan Kell (assistant director). The film consists largely of brief interviews with women who have spaces between their front teeth. Why make a film on this unusual, maybe trivial subject? As the film develops, its organization suggests a larger theme: sometimes society has rather narrow notions of what counts as beauty. After introducing the category, the film examines social attitudes, both positive and negative, toward gap-toothed women. If gapped teeth seem to be flaws at the beginning of the film, by the end, being gap-toothed is associated with attractiveness, energy, and creativity.

We can break

Gap-Toothed Women

into these segments:

- A pretitle sequence introducing a few gap-toothed women

- A title segment with a quotation from Chaucer

- Some genetic and cultural explanations for gaps

- Ways American culture stigmatizes gap-teeth, and efforts to correct or adjust to them

- Careers and creativity

- An epilogue: gaps and life

C. Credits

These segments are punctuated with songs, as well as with still images from magazine covers and photographs that comment on the subject matter of the interviews.

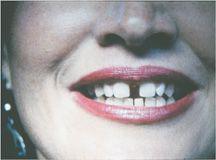

Over the opening title previously quoted, we hear the sound of someone biting into an apple—an odd sound soon explained in the first interview. The opening image is a startlingly close view of a woman’s mouth

(

10.7

)

as she recalls baby-sitting for her brothers and being baffled when her parents knew when she had stolen bites from forbidden sweets. She has a wide gap between her teeth, and a cut to a close view of an apple shows a bite taken out

(

10.8

).

The woman’s voice refers to her parents’ clue: “My signature, which was my teeth marks.”

10.7 In

Gap-Toothed Women,

a close view of a woman’s mouth with a large gap leads to …

10.8 … her “signature” bite on an apple.

Blank sets up the film’s category humorously, making the tooth gap a mark of wry individuality, a woman’s signature. A quick series of closer views of six smiling mouths follows, culminating in a shot of a woman’s entire head. All show gaps and are accompanied by folksy harp music that enhances the cheerful tone.

While quickly establishing the category governing the film, this sequence also sets up a recurring stylistic choice. Usually, documentary talking heads are framed in medium shots or medium close-ups, but Blank also includes many extreme closeups centering on the subjects’ mouths, as in the opening view of gapped teeth (

10.7

). The emphasis is particularly strong here because Blank zooms in on the mouth, as he will occasionally do later, and the background is neutral, as it will often be. Once we’ve learned to notice tooth gaps, we’ll concentrate on the speaker’s mouth even in the more normally composed head shots

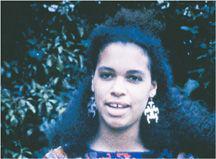

(

10.9

).

Later Blank (in one of his few offscreen comments retained) will coax an elderly woman to grin more broadly to show off her gap

(

10.10

).

As we start to notice the gaps, we register their differences. Some are wide, some narrow, and we’re invited to compare them. By a certain point, the speakers no longer mention them, and the filmmakers seem confident that by then we’ll pay attention to them as a visual motif.

10.9

Gap-Toothed Women:

“My father has a gap, about as wide as mine is; my mom has a gap that’s a little smaller.

10.10

Gap-Toothed Women:

We strain to see this woman’s gap as she smiles at the camera.

The next segment switches to slower shots of a woman playing a harp in a garden. The light, pleasant tone of this opening will be echoed at the end by another, even more buoyant, musical performance. In between, the film explores its subjects’ attitudes toward being gap-toothed.

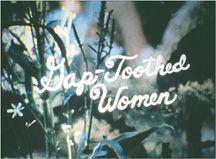

During the harpist’s performance, the film’s title appears in white longhand

(

10.11

).

This writing recalls the initial woman’s reference to her gap-teeth as “my signature.” The title leads to a superimposed epigraph: “‘The Wife of Bath knew much about wandering by the way. She was gap-toothed, to tell the truth.’—Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, 1386

A.D.

” This epigraph suggests that the film’s central category originated long ago. Moreover, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath is traditionally associated with erotic playfulness, and this element will become a motif in the film as a whole.

10.11 The film’s title is superimposed on a garden scene.

The film’s third segment deals with where gaps come from and what they are thought to mean. In a cluster of brief interviews, three women mention that other members of their family had gap-teeth as well, so we infer that this is a natural, if unusual, feature that runs in families. All three women speak in a neutral way about gapped teeth, but the first, mentioning that her mother had worn braces, drops the hint that some people take gapped teeth to be undesirable.

This segment then shifts its focus to how various cultures—specifically, non-white societies—have interpreted gap-teeth. A young Asian woman with a gap speculates on a “stupid” myth that gap-toothed women “are supposed to be sexier.” Blank then cuts to a brief clip from the fiction film

Swann in Love,

with the protagonist making love to a beautiful gap-toothed woman in a carriage. Does this confirm the myth? Or only suggest that the myth has been applied to gap-toothed women in general—since the actress is not Asian? This clip from another film introduces a tactic of intercutting images from art and popular culture with the interview footage, as if to suggest how pervasive ideas about gapped teeth are.

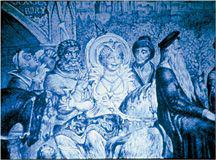

The erotic motif brings back the Wife of Bath, now in an engraving showing her riding at the head of a group of pilgrims

(

10.12

).

A scholarly male voice-over explains that in medieval times being gap-toothed was associated with a love of travel and an amorous nature. There follows a string of interviews developing the motif. A gap-toothed woman tells, in sign language, that she dreamed of kissing her instructor and having their gaps interlock. An African-American woman describes how, in places like Senegal, gaps are seen as lucky or beautiful

(

10.13

).

An Indian woman asserts that in her culture gaps are so normal as not to require comment. Abruptly, Blank cuts to a modern copy of a sphinx, and we hear a woman’s voice claiming that ancient Egyptian women believed that gaps were associated with beautiful singing. Overall, the segment shows that cultures have interpreted gap-teeth very differently, but most don’t consider them flaws and many treat them as signs of beauty.

10.12 In

Gap-Toothed Women,

the image of the Wife of Bath stands out incongruously from the dignified group, with her low-cut dress and broad grin.