B0041VYHGW EBOK (22 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Some unusual supplements include an unconventional production diary for the independent film

Magnolia

and an evocative 8-minute compilation, “T2: On the Set,” of footage from the shooting of

Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

“The Making of

My Own Private Idaho

” demonstrates well how cost-cutting can be done on a low-budget indie.

As previsualization becomes more common, DVD supplements are beginning to include selections: “Previsualization” on the

War of the Worlds

disc (where the animatics run in split screen, beside finished footage), animatics for each part of

The Lord of the Rings,

and the “Day 27: Previsualization” entry in

King Kong: Peter Jackson’s Production Diaries,

as well as a featurette on previz, “The Making of a Shot: The T-Rex Fight” (including the scene in

1.26

).

The marketing of a film seldom gets described on DVD, apart from the fact that trailers and posters come with most discs. There are rare cases of coverage of the still photographer making publicity shots on-set: “Taking Testimonial Pictures” (

A Hard Day’s Night

) and “Day 127: Unit Photography” (

King Kong: Peter Jackson’s Production Diaries

). The same two DVDs include “Dealing with ‘The Men from the Press,’” an interview with the Beatles’ publicist, and “Day 53: International Press Junket,” where

King Kong

’s unit publicist squires a group of reporters around a working set.

In general, the

King Kong: Peter Jackson’s Production Diaries

discs deal with many specifics of filmmaking and distribution that we mention in this chapter: “Day 25: Clapperboards,” “Day 62: Cameras” (where camera operators working on-set open their machines to show how they work), “Day 113: Second Unit,” and “Day 110: Global Partner Summit,” on a distributors’ junket.

Agnès Varda includes a superb film-essay on the making of

Vagabond

in the French DVD, which bears the original title

Sans toit ni loi.

(Both the film and the supplements have English subtitles.) Director Varda’s charmingly personal making-of covers the production, marketing, and showcasing of

Vagabond

at international film festivals. Varda also prepared an affectionate making-of featurette about her husband Jacques Demy’s 1967

Young Girls of Rochefort,

which is available on the British Film Institute’s DVD release.

Hellboy II: The Golden Army

has a lengthy making-of documentary, “

Hellboy

: In Service of the Demon,” that touches on most phases of production.

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest

has two detailed, surprisingly candid supplements: “Charting the Return,” on preproduction, and “According to Plan,” on principal photography.

The Golden Compass

has a series of short documentaries that are more interesting than their bland titles suggest. “Finding Lyra Belaqua” traces the casting process rather than simply showing audition tapes; “The Launch” deals briefly with press junkets and even interviews a junket producer. Other useful making-ofs are “Deciphering Zodiac” (

Zodiac

) and “I Am Iron Man” (

Iron Man

).

For more details on some of the supplements we have recommended in

Film Art,

see “Beyond praise: DVD supplements that really tell you something,” at

www.davidbord well.net/blog/?p=1339

, and “Beyond praise 2: More DVD supplements that really tell you something,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=4004

. On the DVD of

The Da Vinci Code,

discussed in that entry, see “Another little

Da Vinci Code

mystery,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=224

. Further entries in this series will be added occasionally.

Chapter 1

outlined some ways in which people, working with technology, make films. Now we can get a little more abstract and ask other questions. By what principles is a film put together? How do the various parts relate to one another to create a whole? Answering these questions will help us understand how we respond to individual movies and how cinema works as an artistic medium.

In the next two chapters, we will start to answer such questions. We assume that a film is not a random collection of elements. If it were, viewers would not care if they missed the beginnings or endings of films or if films were projected out of sequence. But viewers do care. When you describe a book as “hard to put down” or a piece of music as “compelling,” you are implying that a pattern exists there, that some overall logic governs the relations among parts and engages your interest. This system of relationships among parts we shall call

form

.

Chapter 2

examines form in film to see what makes that concept so important to the understanding of cinema as an art.

Although there are several ways of organizing films into unified formal wholes, the one that we most commonly encounter in films involves telling a story.

Chapter 3

examines how

narrative form

can arouse our interest and coax us to follow a series of events

from

start to finish. Narrative form holds out the expectation that these events are headed toward dramatic changes and a satisfying outcome.

The experience that art offers us can be intensely involving. We say that movies

draw us in

or

immerse us.

We get absorbed in a book or lost in a song. When we can’t finish a novel, we say, “I couldn’t get into it,” and we say that music we don’t like “doesn’t speak to me,” as if it were a sluggish conversational partner.

All these ways of talking suggest that artworks involve us by engaging our senses, feelings, and mind in a process. That process sharpens our interest, tightens our involvement, urges us forward. How does this happen? Because the artist has created a pattern. Artworks arouse and gratify our human craving for form. Artists design their works—they give them form—so that we can have a structured experience.

For this reason, form is of central importance in any artwork, regardless of its medium. The idea of artistic form has occupied the thinking of philosophers, artists, and critics for centuries. We can’t do justice to it here, but some well-established ideas about form are very helpful for understanding films. This chapter reviews them.

Form as System

Artistic form is best thought of in relation to the human being who watches the play, reads the novel, listens to the piece of music, or views the film. Perception in all phases of life is an

activity.

As you walk down the street, you scan your surroundings for salient aspects—a friend’s face, a familiar landmark, a sign of rain. The mind is never at rest. It is constantly seeking order and significance, testing the world for breaks in the habitual pattern.

Artworks rely on this dynamic, unifying quality of the human mind. They provide organized occasions in which we exercise and develop our ability to pay attention, to anticipate upcoming events, to construct a whole out of parts, and to feel an emotional response to that whole. Every novel leaves something to the imagination. A song asks us to expect certain developments in the melody. A film coaxes us to connect sequences into a larger whole. But how does this process work? How does an inert object—the poem on a piece of paper or the sculpture in the park—draw us into such activities?

Some answers are clearly inadequate. Our activity cannot be

in

the artwork itself. A poem is only words on paper; a song, just acoustic vibrations; a film, merely patterns of light and dark on a screen. Objects do nothing. Evidently, then, the artwork and the person experiencing it depend on each other.

The best answer to our question would seem to be that the artwork

cues

us to perform a specific activity. Without the artwork’s prompting, we couldn’t start the process or keep it going. Without our playing along and picking up the cues, the artwork remains only an artifact. A painting uses color, lines, and other techniques to invite us to imagine the space portrayed or to run our eye over the composition in a certain direction. A poem’s words may guide us to imagine a scene, to notice a break in rhythm, or to expect a rhyme.

“Screenplays are structure.”

— William Goldman, scriptwriter,

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Like a painting or a poem, a film employs cues in order to involve us. At the start of

Collateral,

the taxi driver Max is shown wiping down his cab’s dashboard and steering wheel before setting out on his night shift. He then carefully attaches a snapshot to his sun visor. For a moment, he simply gazes at the postcard view of a tropical island. These gestures prompt us to see Max’s personality as neat and orderly. They also suggest that in the city’s turmoil, he clears a quiet mental space for himself. The next scene’s cues reinforce our judgment of Max’s character. While a couple quarrel in the back seat, he tips down the visor and stares at the island vista, as if to shut out the unpleasantness behind him.

We can go further in describing how an artwork cues us to perform activities. These cues are not simply random; they are organized into

systems.

In any system, a group of elements affects one another. The human body is one such system; if one component, the heart, ceases to function, all of the other parts will be in danger. Within the body, there are individual, smaller systems, such as the nervous system or the optical system. One small malfunction in a car’s workings may bring the whole machine to a standstill; the other parts may not need repair, but the whole system depends on the operation of each part. More abstract sets of relationships also constitute systems, such as a body of laws governing a country or the ecological balance of the wildlife in a lake.

As with each of these instances, a film is not simply a random batch of elements. Like all artworks, a film has

form

. By film form, in its broadest sense, we mean the overall system of relations that we can perceive among the elements in the whole film. In this part of the book and in

Part Three

(on film style), we survey the elements that interact with one another. Since the viewer makes sense of the film by recognizing these elements and reacting to them in various ways, we’ll also be considering how form and style participate in the spectator’s experience.

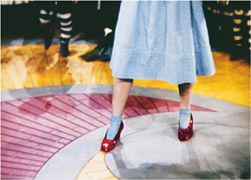

This description of form is still very abstract, so let’s draw some examples from one movie that many people have seen. In

The Wizard of Oz,

the viewer can notice many particular elements. There is, most obviously, a set of

narrative

elements; these constitute the film’s story. Dorothy dreams that a tornado blows her to Oz, where she has adventures. The narrative continues to the point where Dorothy awakens from her dream to find herself home in Kansas. We can also pick out a set of

stylistic

elements: the way the camera moves, the patterns of color in the frame, the use of music, and other devices. Stylistic elements utilize the various film techniques we’ll be considering in later chapters.

Because

The Wizard of Oz

is a system and not just a hodgepodge, we actively relate the elements within each set to one another. We link and compare narrative elements. We see the tornado as causing Dorothy’s trip to Oz; we identify the characters in Oz as similar to characters in Dorothy’s Kansas life. Various stylistic elements can also be connected. For instance, we recognize the “We’re Off to See the Wizard” tune whenever Dorothy picks up a new companion. We attribute unity to the film by positing two organizing principles—a narrative one and a stylistic one—within the larger system of the total film.

“Because of my character, I have always been interested in the

engineering

of direction. I loved hearing about how [director] Mark Sandrich would draw charts of Fred Astaire’s musicals to work out where to put the dance numbers. What do you want the audience to understand? How do you make things clear? How do you structure sequences within a film? Afterwards—what have you got away with?”— Stephen Frears, director,

The Grifters

Moreover, our minds seek to tie these systems to one another. In

The Wizard of Oz,

the narrative development can be linked to the stylistic patterning. Colors identify prominent landmarks, such as Kansas (in black and white) and the Yellow Brick Road. Movements of the camera call our attention to story action. And the music serves to describe certain characters and situations. It is the overall pattern of relationships among the various elements that makes up the form of

The Wizard of Oz.