B0041VYHGW EBOK (98 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.40 … a flashback of her dead German lover’s hand.

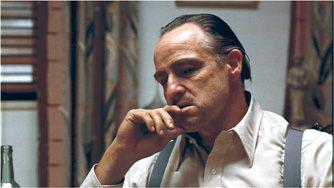

A much rarer option for reordering story events is the

flash-forward

. Here the editing moves from the present to a future event and then returns to the present. A small-scale instance occurs in

The Godfather.

Don Vito Corleone talks with his sons Tom and Sonny about their upcoming meeting with Sollozzo, the gangster who is asking them to finance his narcotics traffic. As the Corleones talk in the present, shots of them are interspersed with shots of Sollozzo going to the meeting in the future

(

6.41

–

6.43

).

The editing is used to provide exposition about Sollozzo while also moving quickly to the Don’s announcement, at the gangsters’ meeting, that he will not involve the family in the drug trade.

6.41 In

The Godfather,

the Corleones discuss their upcoming meeting with Sollozzo.

6.42 Flash-forward: Sollozzo arrives at the meeting, greeted by Sonny.

6.43 The next few shots return us to the family conversation, where Don Vito ponders what he will tell Sollozzo.

Filmmakers may use flash-forwards to tease the viewer with glimpses of the eventual outcome of the story action. The end of

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

is hinted at in brief shots that periodically interrupt scenes in the present. Such flash-forwards create a sense of a narration with a powerful range of story knowledge.

We may assume, then, that if a series of shots traces a 1-2-3 order in the presentation of story events, it is because the filmmaker has chosen to do that, not because of any necessity of following this order.

Editing also offers ways for the filmmaker to alter the

duration

of story events as presented in the film’s plot.

Elliptical editing

presents an action in such a way that it consumes less time on the screen than it does in the story. The filmmaker can create an

ellipsis

in three principal ways.

Suppose a director wants to show a man climbing a flight of stairs but doesn’t want to show the entire duration of his climb. The director could use a conventional

punctuation

shot change, such as a dissolve or a wipe or a fade. In the classical filmmaking tradition, such a device signals that some time has been omitted. Our director could simply dissolve from a shot of the man starting at the bottom of the stairs to a shot of him reaching the top.

Alternatively, the filmmaker could show the man at the bottom of the staircase, let him walk up out of the frame, hold briefly on the empty frame, then cut to an empty frame of the top of the stairs and let the man enter the frame. The

empty frames

on either side of the cut cover the elided time.

Also, the filmmaker can create an ellipsis by means of a

cutaway:

a shot of another event elsewhere that will not last as long as the elided action. In our example, the director might start with the man climbing but then cut away to a woman in her apartment. We could then cut back to the man much farther along in his ascent.

“I saw

Toto the Hero,

the first film of the Belgian ex-circus clown Jaco van Dormael. What a brilliant debut. He tells the story with the camera. His compression and ellipses and clever visual transitions make it one of the most cinematic movies in a long time. The story spans a lifetime and kaleidoscopic events with such a lightness and grace that you want to get up and cheer.”— John Boorman, director

“[In editing James Bond films], we also evolved a technique that jumped continuity by simple editing devices. Bond would take a half-step towards a door and you would pick him up stepping into the next scene. We also used inserts cleverly to speed up a scene.”

— John Glen, editor and director

It’s also possible to expand story time. If the action from the end of one shot is partly repeated at the beginning of the next, we have

overlapping editing

. This prolongs the action, stretching it out past its story duration. The Russian filmmakers of the 1920s made frequent use of temporal expansion through such overlapping editing, and no one mastered it more thoroughly than Sergei Eisenstein. In

Strike,

when factory workers bowl over a foreman with a large wheel hanging from a crane, two shots expand the action

(

6.44

–

6.46

).

In

October,

Eisenstein overlaps several shots of rising bridges in order to stress the significance of the moment.

6.44 In

Strike,

a wheel swings toward the foreman …

6.45 … then swings toward him again …

6.46 … and then again before striking him.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Sit in on an editing session for Johnnie To’s

Mad Detective,

and see some of the final cuts from the film in “Truly madly cinematically.”

We’re accustomed to seeing a scene present action only once. Occasionally, however, a filmmaker may go beyond expanding an action to repeat it in its entirety. The very rarity of this technique may make it a powerful editing resource. In Bruce Conner’s

Report,

there is a newsreel shot of John and Jacqueline Kennedy riding a limousine down a Dallas street. The shot is systematically repeated, in part or in whole, over and over, building up tension in our expectations as the shot seems to move by tiny increments closer to the moment of the inevitable assassination. Occasionally in

Do The Right Thing,

Spike Lee cuts together two takes of the same action, as when we twice see a garbage can fly through the air and break the pizzeria window at the start of the riot. Jackie Chan often shows his most virtuosic stunts three or four times in a row from different angles to allow the audience to marvel at his daring

(

6.47

–

6.49

).

6.47 In

Police Story,

chasing the gangsters through a shopping mall, Jackie Chan leaps onto a pole several stories above them …