B004R9Q09U EBOK (10 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

The first Greek civilization came crashing to an end around 1200 BC, through a series of political disruptions that would be immortalized in Homer’s

Odyssey

. The first Greek kingdoms collapsed, and the region descended into an ancient equivalent of the Dark Ages. The arts of literacy deteriorated and then vanished. State institutions disintegrated, and Greek culture vanished into a historical black hole, leaving almost no written trace for more than two centuries. As the first Greek kingdoms collapsed, people reverted to earlier tribal ways, reembracing their old oral traditions. The disintegration of institutional hierarchies created a fallow ground for ancient social networks to reemerge.

In this renewed oral culture, ancient myths took on new vitality. As we saw in

Chapter 2

, these mythologies were more than just popular stories; they reflected a deep-seated disposition to understand the world in terms of family relationships, shaped by the same epigenetic rules that govern the structure of folk taxonomies. The tales of Greek mythology originated from earlier traditions in Sumer, Babylon, Ugarit, and Bogazköy, which in turn derived from even older tribal myths. These overlapping streams of narrative myth extended like a vast cultural watershed across the ancient Near East. In the structure of these ancient stories, we can find the echoes of old taxonomic hierarchies. Hesiod’s

Theogony

, the canonical version of the Greek myths, portrays a family tree of the gods that runs about five to six levels deep, just like a folk taxonomy, with each god representing a particular element of the natural world. Zeus is the god of thunder, Poseidon the sea, Hades the underworld, and so on. The relationships among the gods describe allegories and metonymies encoded in a structure of “family” relationships.

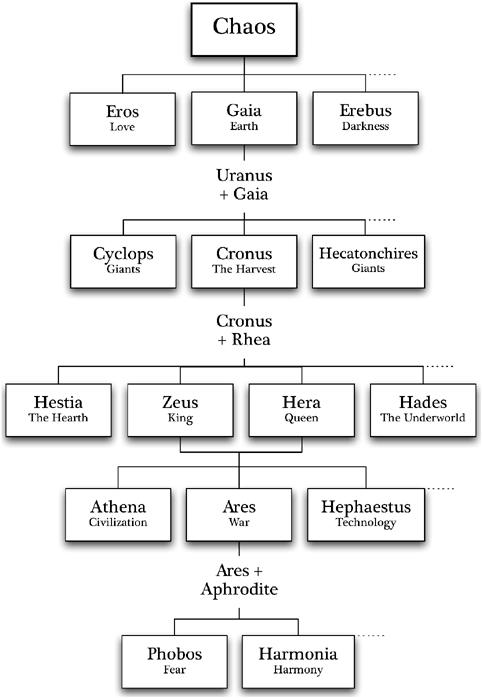

The diagram below shows a partial glimpse of how the family relationships among the gods unfold. Chaos, the primordial abyss, gives birth to Gaia, the Earth, who in turn gives birth to Cronos, the Harvest, who begets the family of gods most familiar to humans: Hestia, Zeus, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Zeus and Hera, the archetypal king and queen, give birth to Athena, the goddess of civilization; Ares, the god of war; and Hephaestus, the god of technology. Ares gives birth to Phobos, the god of fear, and Harmonia, the goddess of harmony. The whole system functions as a kind of vast cultural encyclopedia, cross-referenced using the familiar structure of family genealogy. The stories of Zeus and the gods also narrate metaphorical relationships among natural phenomena. For example, Okeanos and Tethys give birth to rivers and streams; Hyperion and Thela to the sun, moon, and dawn; and so forth. The familiar myth of the Muses—the divine beings said to inspire poets and artists—represents more than just a superstitious belief in the possibility of divine inspiration. “The Muses’ genealogy is transparent allegory,” writes classicist Robert Lamberton. “Offspring of power and memory, they embody the prestige and authority of the highest of the gods.

Memory, in this context, is not the capacity eroded by Alzheimer’s or obliterated by Korsakov’s syndrome but rather a fine-tuned programming in a vast range of cultural skills and information.”

16

The

Theogony

thus serves as a taxonomic prototype for the structure of Greek thought.

A partial genealogy of the Greek gods, adapted from Hesiod’s

Theogony.

While it would be outrageously simplistic to suggest that the rich tapestry of Greek mythology boils down to one big taxonomy, nonetheless the basic structure of these divine genealogies seems to echo the implicit structures of ancient folk taxonomies. Note that the most popular gods—the Olympians—appear roughly in the middle of the hierarchy, in a position corresponding to the genus, the “psychologically primary” category in folk taxonomies (see

Chapter 2

).

The structure of the gods’ families holds glimpses of older oral traditions that predated the first era of Greek kings, traditions that spread through the pure network of oral traditions, unfettered by priestly bureaucracies. “From the earliest glimpses we have into Greek tradition, the poets and visual artists, not the priests, were the bearers of the traditions about the divine,” writes Lamberton. “The contrast with the priest-ridden cultures of the East has often been drawn but cannot be too much emphasized. The Greeks had no Moses, and their first theologians were entertainers—Homer and Hesiod.”

17

In the years following the disappearance of the old state hierarchies during the Greek Dark Ages, poets strengthened their command of the old stories and, by extension, the transmission of cultural tradition.

By the time Greek civilization reemerged from its writing-less silence in the ninth century BC, the Greeks were living in a new world. Poetry had taken the place of scriptures and royal decrees. Soon it would provide the foundation for a whole new kind of literate culture. Whereas the earlier Greek civilization had used a form of writing derived from the imperial Babylonian script, this time the Greeks borrowed a new script from their trading partners, the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians used a phonetic writing system, with letters signifying sounds rather than ideas. The Greeks adapted this alphabet to their native oral language, in the process hitting on a radically simplified style of writing. Their new alphabet contained just 24 symbols. It was easy to learn. In the earlier Greek civilization, literacy had re

quired long years of training and imperial support; it was only for the elites. Now, almost anyone could learn to read and write. This time the Greeks would not succumb to the old imperial “tyranny of the book.”

18

The Greeks took up the new form of alphabetic writing with enthusiasm. While the old empires had used writing largely for affairs of state—government archives, administrative records, hagiographies of their rulers—the newly literate Greeks put writing to more populist ends. Emerging from a period of reengagement with their older oral heritage, mythologies, and folk traditions, the Greeks started writing down their old stories. By the time of the great civic festivals of Athens in the sixth century BC, readers were clamoring for standardized versions of their old myths. This period saw a great shift in the nature of storytelling, from an era when poems enjoyed a fluid structure in the ever-shifting versions of oral storytellers to a more rigid and deterministic form, as poems became “frozen and shackled to the interests of political power,” as Lamberton puts it. While the stories of the Greek myths contained embedded hierarchies of family relationships between the gods, those hierarchical narrative structures also strengthened the bonds of social networks. “Institutions demand—indeed, impose—stability and are able to harness the power of even such unlikely sources as poetry.”

19

While the notion of poems as political tools may strike us as implausible today, the poems of ancient Greece—like the Odyssey, or Hesiod’s mythology—went straight to the heart of questions of political legitimacy. The emerging Greek political institutions had a clear vested interest in nailing down standard versions of these texts as safeguards of their own power. These old tales, preserved through the Greek Dark Ages through the aegis of social networks, became important tools in establishing new political hierarchies.

As the old myths became ensconced in writing and embedded in a growing bureaucratic structure, the Greeks began to approach their old stories in a new light. At first most of these stories had fallen into the category of what psychologist Merlin Donald calls “mythic” or integrative thought, in which cultural knowledge is synthesized in the form of densely layered mythologies. Mythic thought, while it

may be expressed in writing, harkens back to the oral traditions of tribal cultures. The Greeks, however, took their understanding a step farther. They were, as far as we know, the first culture to make the leap from mythic to “theoretic” thought: that is, the ability to reflect on the process of thought itself. Writing gave Greeks the chance to approach their old myths with a new reflexive stance, cultivating a degree of objectivity that enabled them to compare, assess, and excavate new layers of meaning from the texts. By writing down their old stories, they made the inner logics of these systems visible. Once the text became externalized, it could be subjected to analytical thought, reworked, and even improved on. This process of textualization corresponds to what Merlin Donald calls the “demythologization” of culture. “The first step in any new area of theory development is always antimythic,” he writes. “Things and events must be stripped of their previous mythic significances before they can be subjected to what we call ‘objective’ theoretic analysis. In fact, the meaning of ‘objectivity’ is precisely this: a process of demythologization.” For example, astronomy constitutes the demythologization of astrology, chemistry the demythologization of alchemy, anatomy constitutes the demystification of the human body, and so on. “Before nature could be classified and placed into a theoretical framework, it too had to be demythologized,” writes Donald. “Nothing illustrates the transition from mythic to theoretic culture better than this agonizing process of demythologization, which is still going on, thousands of years after it began. The switch from a predominantly narrative mode of thought to a predominantly analytic or theoretic mode apparently requires a wrenching cultural transformation.”

20

This second coming of alphabetic thought left some Greek thinkers with a conflicted relationship to the emerging information technology of the written word. In

Phaedrus

, Plato recounts the story of the Egyptian god Theuth, the discoverer of writing, the “speech of the gods.” When he presents his discovery to the Egyptian god-king Thamus, presumably expecting accolades for his breakthrough, the king instead gives him a sharp rebuke. “This discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in men’s souls,” says the king, “because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written char

acters and not remember of themselves.” The king goes on to decry the art of writing as “an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence,” warning that readers will become “hearers of many things and will have learned nothing … having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

21

This story has often been misinterpreted as Plato’s condemnation of writing. In fact, Plato was a great lover of books. He maintained one of the largest private libraries in Athens. The tale is actually a veiled attack on the Sophists, who devoted themselves to the enthusiastic production of knowledge without, in Plato’s view, a proper reverence for reading. The Sophists’ disposition toward profligate penmanship prompted Aristophanes to deride the ancient Greek capital as “Athens full of scribes.”

Plato’s story also contains the central paradox of writing: Plato surely knew the story could not possibly have survived without being written down. The story seems to recognize the threat posed by literate culture to earlier oral traditions. Yet the interpolation of oral and literate cultures was the essential factor in the Greek contribution to human knowledge.

Poised at the cusp of the transition from oral to literate traditions, the tales of Greek mythology provide a perfect boundary object for analyzing the effects of this profound cultural shift. They give us a revealing glimpse into the mythic world of the oral traditions that preceded the reemergence of Greek literacy, showing how mythologies rooted in ancient wisdom traditions provided the cultural framework for the great Greek experiment with decoding the process of “knowing” itself. “From the first, Greek thinkers were employing external memory devices to their fullest effect, in a way that was totally new,” writes Donald.

In modern culture, narrative thought is dominant in the literary arts, while analytic thought predominates in science, law, and government. The narrative, or mythic, dimension of modern culture has been expressed in print, but it is well to keep in mind that in its inception, mythic thought did not depend upon print or visual symbolism; it was an extension, in its basic form, of the oral narrative.

22

Analytic thought gives rise to “formal arguments, systematic taxonomies, induction, deduction, verification, differentiation, quantification, idealization, and formal methods of measurement”—systematized ways of understanding the world that are all absent from the world of mythic thought.

23

“[T]he natural tendency of spoken thought … is toward fairly loose narration of events, metaphoric fantasy, and storytelling. Fine-grained analysis of the thought process itself is difficult, because the memory trace of an oral narration is so ephemeral.”

24

The new art of “thinking about thinking” opened the door to introspection—formalized ideas and conjectures, unfinished thoughts, and dialogue. The process of demythologization not only affects the forms of human thought but also influences macro structures of social organization. Whereas oral traditions lend themselves naturally to fluid, self-organizing social networks, written analytic thought creates a different imperative, fostering the kind of linear thinking that seems to beget organizational hierarchies. Donald speculates that “the governing cognitive structures of the most recent human cultures must be very different from those of simple mythic cultures. They exist mostly outside of the individual mind, in external symbolic memory representations, which are dependent upon visuographic invention, and they culminate in governing theories.”

25

In other words, the shift from mythological to analytic culture played out in the evolving structure of the state itself.