B004U2USMY EBOK

Authors: Michael Wallace

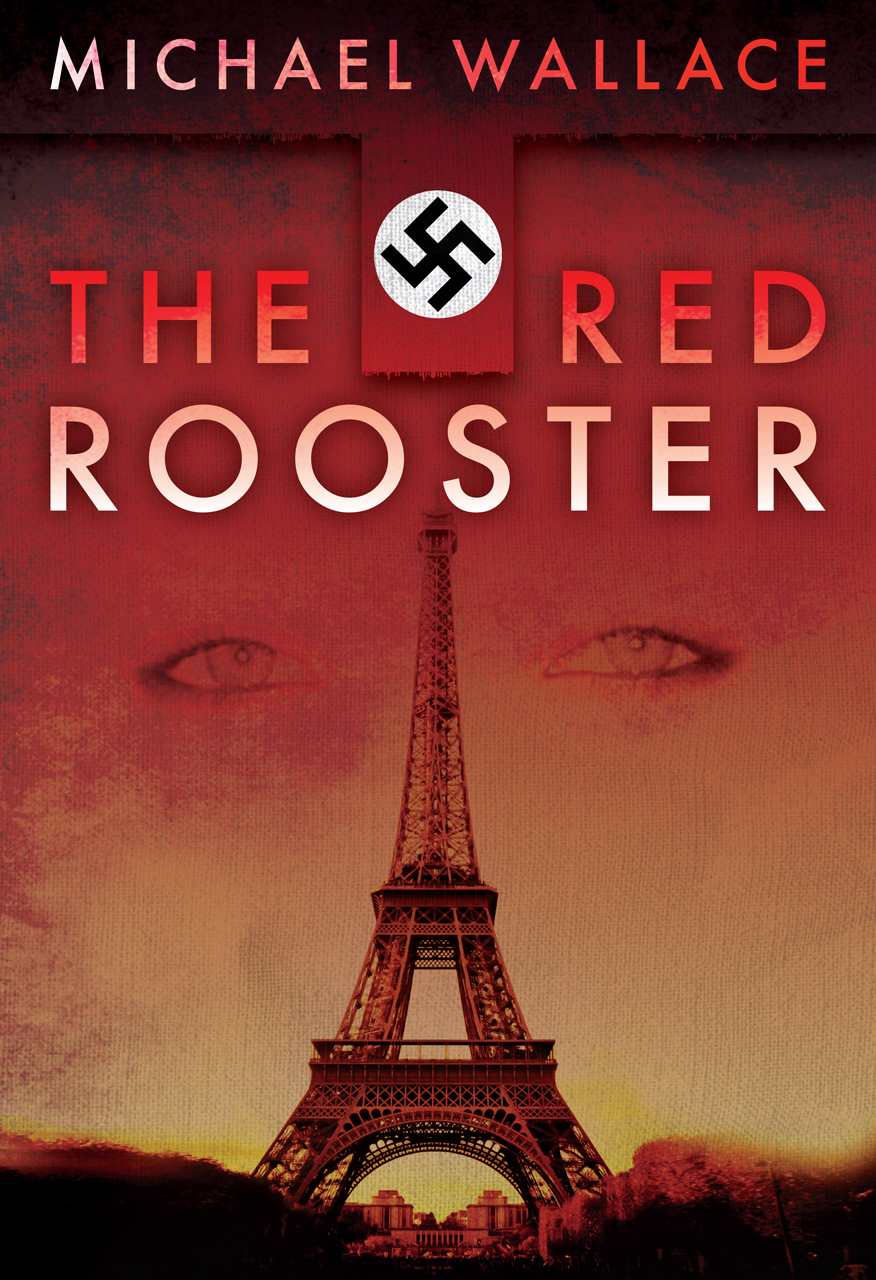

The Red Rooster

by Michael Wallace

Copyright © 2011 by Michael Wallace

original cover art by Jeroen Ten

Berge - http://jeroentenberge.com/

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away. If you

would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with.

Thank you for respecting the author's work.

Prologue:

June 2, 1940

Among the throngs fleeing the port at Dunkirk

was a young woman from Spain, seventeen years old, who wanted to

return to the front lines. She had passage across the Channel,

papers paid for with a man’s life and a small fortune in twenty

franc notes, and a cousin waiting in London. She kicked off her

shoes, gathered her dress and prepared to jump overboard.

The captain of the overburdened boat grabbed

her arm with a bandaged hand. His eyes were wild. “Stupid girl,

you’ll die, you’ll never make it.”

Gabriela barely heard him, could only think

about her father and it made her angry and afraid.

You lied. You said you were coming back

and you never meant it.

Instead, he’d left her on this shot-up

listing fishing boat, lashed to the side of the British gunboat

and crowded with children, embassy staff, and soldiers. He meant

to face the Germans without her.

“What’s wrong with you, aren’t you

listening?” the captain said. “Fine, die for all I care, I won’t

stay a minute longer.”

Gabriela braced herself and jumped.

The water was cold. She went under and into

silence. Gone were the shouting, cursing soldiers, the rumble of

artillery and the high-pitched whine of brawling fighter planes,

the British destroyers hurling shells across the water and into

the city.

She came up in a wreckage of splintered oars,

broken barrels, shoes, army jackets, papers, flailing people with

or without life jackets. The water tasted bitter, oily. An

explosion, a spout of water. Anti-aircraft fire sliced the sky

against two screaming dive-bombers. She paddled toward the beach,

and the hundreds of British and French soldiers wading into the

water.

A soldier pulled her onto the beach, asking

questions in English, what sounded like a variation of what the

fishing boat captain had been screaming.

“No, I’m going back, I need to find my

father. Let go!”

More English, two soldiers now, trying to

calm her, take her back into the water and toward the ramshackle

flotilla evacuating the beaches. Gabriela struggled and kicked and

finally they let her go. She ran barefoot across the sand, back

toward town. Burning half-tracks littered the beach, together with

overturned trucks, an aircraft fuselage, rifles tossed in piles by

fleeing soldiers. The ground shuddered, threw her down. She picked

herself up.

Her father had lied, he’d stuck his head in

the noose to save her. He’d sacrificed himself, and for what? Did

he think she’d take it?

Chapter One:

September 18, 1942

The Italian waggled his finger in Gabriela’s

face. “Eleven francs. No more.”

She extended the jade brooch until she held

it under his nose. “Please, look closer.” Gabriela fought to keep

from sounding desperate, a difficult task two years into her

nightmare. “The dragonfly wings are so delicate, and look at the

detail. How about thirteen, it’s just two more francs.”

He shook his head without looking down.

“Eleven.”

“There are other stalls, you know.”

Sure, and you’ve tried them all, haven’t

you?

A hundred other stalls, and ten thousand

people in worn shoes and threadbare socks, empty stomachs, some

with hungry children, all trying to offload their last, precious

possessions.

Gabriela owed her landlords thirty, had sold

almost everything she owned, and was down to selling half her

ration cards so she could buy food with the other half. What good

would eleven francs do? Thirteen, for that matter?

“Eleven. Take it or not.”

She pulled back her hand. “My father gave

this brooch to my mother. She’s dead. I can’t possibly sell it for

eleven francs.”

“Listen girl, nobody cares.” The voice

belonged to a woman queued behind her, holding silk scarves.

Behind her, a man with a pair of silver candlesticks who looked

suspiciously like a Jew. In the

marché aux puces,

nobody much bothered with that.

She’d seen

all types in the flea markets of Paris. Hadn’t she been here a

hundred times to sell her father’s things?

His boots,

belts, greatcoat, books of Spanish poetry, leather journals, his

watch, even paintings of mother; all brought a few precious

centimes or francs. Two weeks ago she’d sold the trunk itself,

brought from Spain.

She kept a few meager possessions, her

favorite of which was his meerschaum pipe, amber from years of

smoking. It still held the aroma of tobacco and she couldn’t smell

it without imagining him in his chair. When she came in and saw

him smoking, she could almost see the cloud of thoughts rising

above his head with the pipe smoke. He would urge her to sit down,

pull out a small wooden box of imported Belgian chocolates, and

then pontificate: rubber plantations in Ceylon, the proper ratio

of shellfish to sausage in a mixed paella, or the development of

the steam engine. It didn’t matter the subject, he was so

energetic that she would sit and listen, eating chocolates while

he gesticulated with his pipe and his latest book.

Selling the pipe would be like selling those

memories.

The stall

owner’s scowl hardened. “Eleven. Either make a deal or get the

hell out of my line. I’m busy.”

“All right, then, eleven.” She made to hand

over the brooch to the stall owner, already fumbling in his pocket

for the bills, when a young woman took her wrist.

“Eleven francs, are you crazy?” the woman

asked.

The speaker was close to Gabriela’s own age.

She had a fresh, carefree air and looked glamorous in her green

dress with dainty straps over the shoulders. Nylons, a whiff of

perfume, red lipstick, long eyelashes.

“That’s all I can get,” Gabriela said. “I’ve

tried, God help me.”

“Don’t let this man rob you. I’ll pay you

twenty, how about that?” The other girl opened her purse. She

pulled out some mixed bills that included reichsmarks and francs.

“Twenty. Do we have a deal?”

“Hey, what are you doing?” the Italian

demanded. “That’s mine, I bought it already.” He shoved his money

at Gabriela and grabbed for the brooch.

She jerked it back. “This woman says twenty.

Will you give me more?”

“Dammit, we had an agreement.” He turned his

anger to the young woman. “You, who do you think you are?”

The young woman laughed and gave a brushing

off motion. She took Gabriela’s arm and led her a few paces from

the crowd. Her heels clicked smartly on the pavement.

Gabriela worried the stall owner would pursue

them, but he was already haggling with the owner of the scarves,

while the queue of sellers patiently waited their turn. Meanwhile

the crowd swirled around them. Children, begging. Young, shiftless

men. An old war veteran in his cloak, toothless and smelling of

whiskey and sour sweat.

“I can’t believe he thought you’d take

eleven. May as well steal it. Your brooch is worth at least twice

what I offered, you know that.”

“Maybe before the war.”

The young woman held out the money. “If you

want to ask around for more, I understand. Otherwise, I’m

delighted to pay twenty. It’s a beautiful brooch.”

“No, no, I’ll take it.”

Gabriela took the twenty francs and handed

over the brooch before the girl could change her mind. She tucked

the money into her bra, glanced around to make sure she hadn’t

attracted the attention of pickpockets. Her gaze caught the

uniformed Germans who idled in the shade at the edge of the

street. The Eiffel Tower lifted behind them, topped by a swastika

flag that flapped back and forth in a lazy salute. One man smoked

a cigarette, while the other polished his rifle butt with a

handkerchief.

She was always searching for one German in

particular, the man who knew about Papá. These two were just

ordinary soldiers.

“It’s beautiful,” the girl said. “I feel so

guilty. I should have paid you more.”

“Thank you anyway, you were generous,”

Gabriela said, using the formal address in French.

“Oh, don’t give me that

vous

nonsense. It’s so formal and stuffy, and I’m not that old. How old

are you?”

“Almost twenty.”

Am I? My god, has it been two years

already?

“See, I knew it. We’re the same age. My name

is Christine.”

“I’m Gabriela. Gaby, I mean.”

“Well, Gaby, I took advantage of you, I admit

it.” She held up the brooch, admired it, then slipped it into her

purse. Gabriela felt a pang of loss. Her mother’s brooch, and now

it was gone. At least she’d sold it for more than she’d dreamed

just a few minutes earlier.

“Are you from Paris?” Christine asked.

“No,” she admitted.

“I’m so glad. I’m tired of these snobby

Parisiennes. Oh! I’m ready to faint I’m so hungry. You must be

too, arguing with that horrible Italian. Can I buy you a sausage?

I know a man who sells them out of a cart.” She gave Gabriela a

confidential smile. “No ration coupons required.”

Gabriela would have declined out of polite

habit, not to mention the punishing urge to go back to her

cramped, dingy flat she shared with her landlords and curl into a

ball, but her stomach growled so loudly at the mention of sausage

that she thought it must have been audible over the shouting

touts, the haggling, the crying children. “Yes, please. That would

be very nice of you.”

The sausage, when tracked down from the

illegal vendor, was obscenely expensive compared to pre-war

prices, and just as obscenely good. It had been weeks since

Gabriela had tasted meat and that had been a scrap of chicken, so

dry it was almost desiccated. This was thick and juicy. She took a

bite and rich fat, hot and delicious, slid down her chin.

Christine laughed and helped her clean it up with her

handkerchief.

“I’m sorry,” Gabriela said around mouthfuls.

Her fingers were burning on the wax paper, her tongue burning too,

but she didn’t care. “I haven’t had lunch. In fact, I haven’t had

a proper meal for about three weeks.”

A thin girl of four or five stared at them

eating. She clutched her mother’s dress. The mother tried to sell

bunches of daisies to passersby.

Christine took her elbow and led her away. “I

know what that’s like. Times are tough.”

“Times are tough?” Gabriela put a smile into

her voice. “Isn’t that like observing there are Germans in Paris?

Or saying a lot of Catholics hang around Notre Dame?”

Christine laughed. “Well, I hope the money

comes in handy. Hey, are you waiting for someone?”

“What? Oh, no. Not really.” Gabriela realized

she had been scanning the crowd again. Looking for the Gestapo

agent who could help her find her father.

“Who do you live with? Your parents?

Husband?”

Gabriela shook her head. “I don’t have

anyone. I’m fighting it out by myself.”

“But where do you live?” Christine asked.

“With my landlords in the 14

th

Arrondissement. Not so nice, but it keeps me warm.”

“You may not believe it, but I know what

that’s like. I have to work to keep fed.”

“Oh, you have a job?” Gabriela found herself

reappraising Christine. Not a rich girl then. But what kind of job

paid well enough to buy black market sausages for strangers?

“I grew up near Marseille. Came up with my

sister a couple of years ago, but her husband went east on a work

crew—POW, you know—and she got permission to join him in Germany.

My mother wants me back in Provence. Probably to get married, but

she won’t admit it. I don’t want to go, so I got a job in a

restaurant called Le Coq Rouge, in the 4

th

. You know

the place?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Good food, nice people. You should stop by

some time. Maybe you could, I don’t know, get a job.”

Work in a restaurant sounded perfect.

Something to feed herself while she continued her search for Papá.

Gabriela had already scoured the city for work, of course, but

never managed to find anything, and wondered how Christine had

managed.

“What do you do, wait tables?” Gabriela

asked.

“Not exactly. I’m more of an entertainer.”

“And that’s what you do at the restaurant?

Entertain Germans?”