B008AITH44 EBOK (15 page)

Authors: Brigitte Hamann

CHAPTER THREE

P

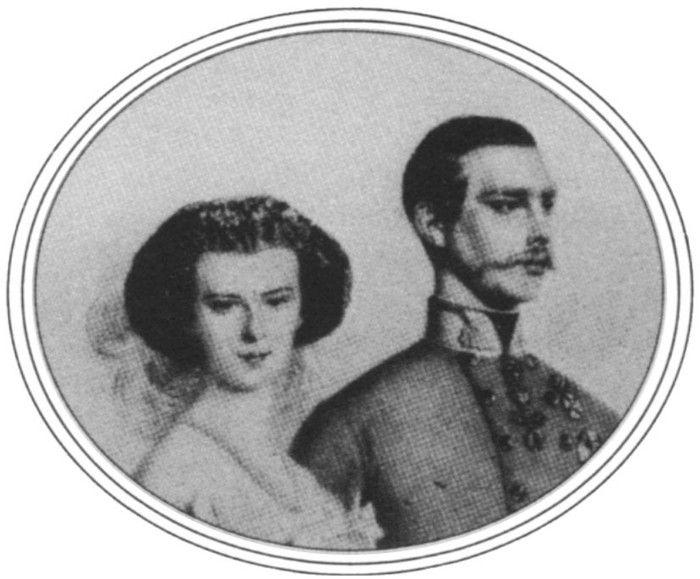

roblematic as Sisi’s position at the court of Vienna and her relations with her mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie, might have been, the relationship between the Emperor and Empress was excellent. It was impossible to ignore the fact that Franz Joseph was deeply in love. And there can be scarcely any doubt that Sisi returned her husband’s feelings and was happy with him.

The couple’s first child was a girl, little Sophie. We have Archduchess Sophie to thank for a detailed description of the birth; her diary records a veritable idyll.

On the morning of March 5, 1855, the Emperor woke his mother at seven o’clock because Sisi’s pains had started. Taking along a piece of needlework, Sophie sat outside the imperial bedchamber and waited, “and the Emperor went back and forth between her and me,” she wrote.

When, around eleven o’clock, the pains grew stronger, Sophie joined the Emperor at her daughter-in-law’s bedside, observing the couple’s every move.

Sisi held my son’s hand between her own two and once kissed it with a lively and respectful tenderness; this was so touching and made him weep; he kissed her ceaselessly, comforted her and lamented with her, and looked at me at every pain to see if it satisfied me. When they grew stronger each time and the birth began, I told him so, to give Sisi and my son new courage. I held the dear child’s head, the chamberwoman Pilat held her knees, and the midwife held her from behind. Finally, after a few good long labor pains, the head appeared, and immediately after that, the child was born (after three o’clock) and cried like a six-week-old baby. The young mother, with an expression of such touching bliss, said to me, ‘oh, now everything is all right, now I don’t mind how much I suffered!’ The Emperor burst into tears, he and Sisi did not stop kissing each other, and they embraced me with the liveliest tenderness. Sisi looked at the child with delight, and she and the young father were full of care for the child, a big, strong girl.

The Emperor accepted the congratulations of the family assembled in the anteroom. After the baby was washed and dressed, Sophie held it in her arms and sat next to Sisi’s bed, as did the Emperor. They waited until Sisi fell asleep, around six o’clock. “Very contented and cheerful,” the imperial family took tea. The Emperor joined his younger brother Max for a cigar and a chat. Services of thanksgiving were held in all the churches.

Hardly anywhere else is Sophie’s paramount position in the imperial family as evident as in this special situation. The midwife followed her orders. The Emperor, unsure of himself like any young father, anxiously searched his mother’s expression for indications about the progress of the birth. Elisabeth, who had just turned seventeen, was without her mother’s support, wholly at her mother-in-law’s mercy. Nevertheless, even during the strongest labor pains, her demeanor was one of “reverent, respectful tenderness” for Franz Joseph, as Sophie wrote.

1

It was such demeanor that Archduchess Sophie expected as a matter of course from the young

Empress

in every situation, even in this extraordinary one.

Sisi’s later complaints that the child had been taken from her right after the birth must, however, be taken with certain reservations. At least during the first few weeks after the birth, matters cannot have been quite so bad. Three weeks after her confinement, the young Empress wrote to a relative in Bavaria, “My little one really is already very charming and gives the Emperor and me enormous joy. At first it seemed very strange to me to have a baby of my own; it is like an entirely new joy, and I have the little one with me all day long, except when she is carried for a walk, which happens often while the fine weather holds.”

2

But, of course, the young mother had to submit to her mother-in-law’s regime without remonstrating—just as the Emperor was used to doing from childhood. The child was given the name Sophie, her grandmother being the godmother. Sisi was not consulted on this decision, either.

Until her death in 1857, little Sophie held a special place in her

grandmother’s

heart. Pages of the diary are covered with the details of infant care. Everything aroused the grandmotherly pride of the Archduchess, who was normally so cool: The slightest development, every new tooth became worthy of being recorded in the Archduchess’s diary. Of course, this grandmotherly ardor—her possessiveness—aggravated the problems within the imperial family. The seventeen-year-old, inexperienced

Elisabeth,

intimidated, gave ground; not even the birth of a child had been able to improve her standing at court.

Little more than a year later, in July 1856, Sisi gave birth to another girl. She was named Gisela—after the Bavarian wife of the first Christian King of Hungary, Stephen I. This time Duchess Ludovika was the

godmother,

though she was not present at the christening and was represented by Archduchess Sophie—giving rise to further gossip. We do not know the reason why, in spite of Sisi’s pleas, Ludovika delayed for so long visiting her daughter and her first grandchildren in Vienna. We can only infer from some of Ludovika’s other statements that she was anxious to forestall any jealousy on Sophie’s part.

The disappointment at the fact that once again the hoped-for heir to the throne had not been born was great. The populace was probably most unhappy because the people had reason to expect especially generous benefactions at the birth of an heir to the throne, and during these bad times, the country was in desperate need of succor from any quarter.

This child, too, was handed over to her grandmother’s supervision. Later, Elisabeth expressed deep regret that she did not have a close

relationship

with her elder children, and she always blamed her mother-in-law. Only with her fourth child, Marie Valerie, did she assert her maternal

rights, and she confessed, “Only now do I understand what bliss a child means. Now I have finally had the courage to love the baby and keep it with me. My other children were taken away from me at once. I was permitted to see the children only when Archduchess Sophie gave

permission.

She was always present when I visited the children. Finally I gave up the struggle and went upstairs only rarely.”

3

No matter how insignificant Sisi’s position at court was, her popularity among the populace kept growing. This popularity also had a political basis. For after the Emperor’s marriage, some cautious efforts at

liberalization

were undertaken. The state of siege in the larger cities was gradually raised, and these proclamations always occurred on the occasion of family events, such as the Emperor’s wedding and the births of his children. Political prisoners were released before they had served their full term or were granted amnesty.

The new military penal statute of January 1855—that is, only a few months after the Emperor’s wedding—also brought some easing of

restrictions.

This law abolished among others the punishment, still practiced in Austria, of running the gauntlet. Popular belief would have it that it was the young Empress who had asked her husband to do away with this torture as a wedding present to her. The sources furnish no proofs for the theory; but it is very likely that the extremely sensitive young Empress witnessed such a punishment during one of the numerous military visits or at least heard about it.

4

And it was thoroughly in character for her to have spoken out forcefully against such cruelty. The abolition of keeping prisoners in chains was also attributed to Elisabeth’s initiative. No one had any doubt that these measures could not be attributed to Archduchess Sophie’s influence. For she continued to advocate extreme harshness toward the revolutionaries of 1848 and all other insurgents. Patriotic Austrians loyal to the Emperor were only too ready to believe in the benevolent influence of a new Empress who was in sympathy with the people.

Whether Elisabeth truly had such a direct influence on the Emperor we do not know. But there is no doubt that under his rapturous love and the happiness of his new marriage, the Emperor grew more gentle and

yielding,

and for that reason if no other, he showed himself less firmly opposed than before to liberalizations, which were overdue.

The very young Empress became something like a political hope for all those who felt uneasy under the neo-absolutist regime. The opponents of the Concordat also soon rallied around the Empress. The signing of the Concordat of 1855 constituted a high point of political Catholicism in Austria, at the same time that it was a triumph for Archduchess Sophie,

who was thus able to impose her concept of a Catholic empire: The state yielded to the church the power over the regulation of marriage and over the schools. From this time on, the church had the ultimate decision, not only over the contents of the curriculum (from history to mathematics), but also over the selection of teachers. Even the drawing master and the physical-education teacher had to meet the first requirement—that of being good Catholics (which was checked out down to the taking of the

sacraments

). Otherwise, they would not be given posts. The Concordat was throwing down the gauntlet to all non-Catholics and Liberals, as well as to scientists, artists, and writers, whose work was severely impeded.

The opponents of the Concordat believed that they had found a

sympathizer

in the young Empress—whose conflicts with Archduchess Sophie could no longer be kept secret. They may have been right up to a point. Thus, a characteristic story made the rounds in 1856. The small Lutheran congregation in Attersee wished to erect a steeple on its little church, as was recently permitted, and it needed funds for the project. The pastor turned to the court, which happened to be in residence in nearby Bad Ischl, and he met with the Empress herself. Later, the liberal

Wiener

Tageblatt

reported that the young Empress had begun the interview by expressing her surprise “that the Protestants are for the first time being allowed to build steeples on top of their churches. Where I come from,” she said in a cordial way, “your coreligionists have enjoyed these rights, as I know, for fifty years already. My late grandfather [King Maximilian I of Bavaria] used state funds to let the Protestants build the handsome church on the Karlsplatz in Munich. The Queen of Bavaria [Marie, the wife of Maximilian II] is also a Protestant, and my grandmother on my mother’s side was a Lutheran. Bavaria is an arch-Catholic nation, but the Protestants among us surely have no cause to complain about discrimination or infringements.”

The Empress made a generous donation, though it was said to have “caused great surprise in clerical circles.” The quarrelsome Bishop Franz Joseph Rüdiger of Linz was said to have “requested a formal clarification of whether the matter was true as reported.” The newspaper of the clericals in Linz presented the “incident” from the viewpoint “as if the Empress had not been precisely informed about the actual purpose of the donation, and as if it had been presented to her that the subject was a poor congregation in general terms, but not that it was a Protestant one. The pastor, however, defended himself with a ‘correction’ in the official Linz newspaper.”

5

With this innocent donation for a Protestant steeple, Elisabeth became marked, whether she wanted to be or not, as an adherent of tolerance in

religious questions and as opposing the Concordat. From then on, one faction placed its hopes in her, while the other—and this was the “clerical” party of her mother-in-law, Archduchess Sophie—saw her as an opponent. Sisi’s relations to the court and the aristocracy were anything but improved by these hopes of the Liberals.

*

Sisi’s behavior within the family circle also gradually changed. She was becoming ever less submissive, ever less quiet. She was more and more aware of her exalted position: She was the Empress, the first lady of the land.

This also meant that she dared to oppose her mother-in-law, who had ruled unchallenged until that time. Of course, the first bone of contention was influence in the imperial nursery. At first, Sisi received no support from the Emperor. It was not until 1856, when she was alone with her husband during a journey through Carinthia and Styria, that Sisi insisted that the children be allowed to be near her. Far from the Hofburg, far from the daily shared meals with her mother-in-law, she finally felt strong enough to free the Emperor from his excessive servility toward his adored mother and to remind him for once of his wife’s needs.

An open quarrel now broke out between Sisi and Sophie over the two little girls. Sophie resisted Sisi’s urgent pleas to move the nurseries. She raised a number of objections (the rooms in question did not get enough sunlight, and similar concerns). When Sisi would not give in, Archduchess Sophie threatened to move out of the Hofburg—her strongest weapon. And this time the young Empress managed to pull her husband to her side—to judge from Franz Joseph’s letters, it was the first and only time that the Emperor rebuked the mother he adored.