Back of Beyond (23 page)

If I’m in a reading mood I’ll seek out the longest, least interrupted way of reaching my next destination (night trains in India justify a caseload of reading material), cocoon myself in a corner, and devour words, rhythms, images, textures, emotions, even little wisdoms, with the appetite of an aardvark.

By the time I arrive home, travel wearied and ready for days in the tub, half my baggage is books. Shirts, socks, and underwear rarely seem to make it back but my beloved books do, torn, covers rubbed raw from jiggling about on buses with no shock absorbers, buckled from dousings in streams and monsoon storms, scribbled on (blank pages at the back teeming with “notes to myself” of varying degrees of lunacy). But they’re home with me, safe and loved.

So I dozed and I read John Krich’s “bad mood” travel odyssey

Music in Every Room

(my latest find) and dozed again. There was no point moving on any further. The storm gave no signs of easing and it was getting dark anyway. Another sandwich, a sip or two of whisky…I’d feel fine tomorrow.

Oozing into morning wakefulness. A slow, crisp dawn; strips of scarlet and gold on the gray walls of my cave. Lighting the stove again and feeling the heat rise. Pulling down my “door” of frosted trousers and shirt and looking out across the lochans and bogs bathed in a soft amber glow. No wind. No hail. A few flecks of ice on the ground outside, nothing worse…and no melancholia. The night had done its repair work. I felt fresh again (a little stiff maybe but that would pass). The storm had long since bansheed up the valley, over the towering cliffs and screes of Sgorr Dubh. Everything was at rest now. My traveler’s lethargy had disappeared. It would be a good day today.

And it was. I took my time repacking the rucksack and fixing the broken shoulder strap. My boots were dry enough for walking. The rest was easy.

Leaving my cave I found firm ground, a dry sheep track, and, after another hour or two, at tiny Loch Gaineamhach, the semblance of a footpath heading slowly downhill for miles to Shieldaig. Much, much later came the most wonderful sight of all—rose-colored Shieldaig Lodge and all the Victorian comforts of home in this restored hunting lodge overlooking Loch Gairloch.

Later that evening a weary, but very happy (and well-bathed) wanderer sat down at a window table watching the stars twinkle over the water, feasting on home-smoked salmon, venison pie, and summer-pudding. What more could a bruised bog trotter ask for? I had paid the first installment of my dues to this wild country, and I was content to rest for a while on a laurel or two (albeit rather small ones).

ENGLAND—THE PENNINE WAY

The subtle art of bog trotting still eluded me.

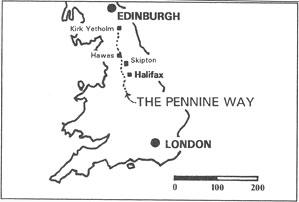

For the eighth time in as many minutes I was calf-deep in a slurping black goo that clung gleefully to my walking boots. After five hours of my journey I was seriously questioning the sanity of my attempt to conquer the Pennine Way, a 270-mile footpath across some of Britian’s wildest country, up the spine of England.

“Oh it’s an easy two or three weeks’ walk,” I’d been assured by experienced members of the Ramblers’ Association. Inspired in the 1930s by journalist Tom Stephenson’s idea for a national equivalent to the Appalachian Trail, the Ramblers made him their leader and finally achieved such a route after years of “mass trespasses” across privately owned moorlands. In 1965 the Pennine Way was declared the first of Britain’s nine official long-distance footpaths, which now total over 1,650 miles.

Today, the ninety-one-year-old Stephenson is amazed by all the recent enthusiasm for walking: “I did my little bit, but I had no idea it would ever be the way it is now. Quite marvelous!”

“It’s a big, wet, soggy mattress for the first twenty-odd miles,” said Gordon Danks in the information center at the start of the footpath at Edale, in Derbyshire’s Peak District National Park. Andy Barnard of the National Trust warned: “People don’t believe you when you explain how bad it can get. They get lost, they don’t trust their compasses, they panic, and they end up in the oddest places way off course and waist-deep in bogs, or,” he added somberly, “worse.” He advised me to leave the name and address of my next-of-kin.

Wild desolation is characteristic of much of the route, which meanders like an inebriated snail along northern England’s mountainous “backbone” from Edale to Kirk Yetholm, a few miles over the Scottish border. This is not the picture-postcard England of thatched cottages and downy woods. Much is treeless terrain especially in the boggy moors of the south.

After the first fifty miles of this kind of soul-grinding terrain many contenders retire. Tom Stephenson estimates that only around six thousand manage the whole distance annually: “It takes a heck of a lot of stamina, determination, and real spunk to finish.”

Those who persevere after the first boggy stretch still have a long way to go among the limestone mountains of North Yorkshire, cut by glaciated “dales,” across the bold intrusions of hard dolerite “sills,” over the Northumberland fells and the grumpy stumps of old volcanoes in the Cheviot Hills.

“Oh, but it’s such fine country,” said Arthur Gemmell, member of the Open Spaces Society and creator of a series of footpath maps for the Pennines. “You can see just about every phase of history here—Iron Age hill forts, Roman roads and Hadrian’s Wall, farms and villages started by Anglo-Saxons and the Norsemen, remnants of the Norman feudal system—particularly those superb abbeys—Fountains, Bolton, Jervaulx, and the others. The church was all-powerful in those days—the monks ran huge sheep farms in the Yorkshire Dales. But the Scots kept coming down and stealing the livestock and the women, so the barons built those castles in the main market towns—Richmond, Barnard Castle, Middleham, Penrith. You slice right through the last two and a half thousand years of English heritage when you walk up here. There’s a tremendous sense of endurance and permanence. But;” he added, like the others, “watch your step. It’s hard going.”

Yet after all the warnings, demure Edale (starting point of the Pennine Way) throbs to the thud of walking boots for much of the year. While villagers hide behind peek-a-boo curtains, hundreds of hikers from tiny Cub Scouts to gritty bog trotters, with formidable boots and enormous framed rucksacks, gather on summer weekends around the Old Nag’s Head pub to prepare for their individual odysseys.

I joined them in the quieter fall, sketchbook in hand, looking for adventures and fresh understandings of regions I had roamed as a youth. I prayed for fair weather but knew the Pennines are no respecter of seasonal fripperies. They’ll turn a balmy day into a rollicking thunderstorm at the twist of a thermal. Equally obtusely, while the distant plains lie sniffling under blankets of fog and drizzle, the air up on the tops can be as crisp as the crust on a well-baked Yorkshire pudding.

After all the initial wallowing, walkers are delighted to find a neat footpath of chestnut pailings tied together and packed down by sandy gravel. “This used to be terrible here,” said Geoff Truelove, a hiking enthusiast. He was out looking for remnants of old aircraft wrecks on Bleaklow and Featherbed Moss and had found seven so far, including a World War II Lancaster and a Boeing Fortress with engines still intact.

“People were coming across the moor in all directions so they put this path in to keep them on course.” He forgot to mention that it finished half a mile away in a dip, reverting promptly to molasses. Peaty streams burst like frothing ale from the soggy hills all around. A haze of heather flowers floated over the moor like a mauve mist.

By Black Hill, though, I was taking the tussocks with the best of them, and in a surge of complacency, made errors that could have been fatal. I had joined a morose bunch of hikers protesting some proposal for yet another reservoir in these overburdened hills. A turnout of thousands had been hoped for but there were eleven in all. We climbed up Laddow Rocks to an undulating ocean of mud and jollied along swapping tall tales of hiking exploits, until one of the girls fell and twisted her ankle, and they all decided to go back.

“Clouds are comin’ down. It’ll mist up, sithee,” said one of the group. With a knowing scowl and a warning of, “Think on na’,” he left, taking my compass by mistake. I didn’t miss it until an hour later when his prediction proved all too accurate and the mist came down, thick and chill.

Following other people’s tracks was useless. The Pennine Way name suggests a clarity of route that rarely manifests itself on the ground. It is invariably tenuous and, in a mist, invisible. I was quickly lost, wandering in bad-tempered circles with all sense of orientation gone. There was nothing to do but sit it out in a sheltered spot, munching on such legendary hiker’s energy snacks as Kendal Mint Cake and other sugary delights, bought more for effect than use the previous day.

It darkened and the mist thickened, swirling wraithlike around hags of worn peat in the gloom. I experienced a gray surge of blind, unreasoning fear and felt enormously alone. Things seemed to be moving out there, and strange gurgling sounds came from the bogs. I gave up all hope of leaving the moor that night, cocooned myself in an enormous plastic survival bag (a joke gift from my sister), thought of Caribbean beaches and Christmas dinners, and half slept through a fitful frosty night.

By dawn the mist had lifted into ponderous low cloud and I felt to be the only survivor in a dead world. Then two silly sheep popped up suddenly from a grough and looked so startled to see me that I bellowed with laughter, and the day became promising again except for a head cold, souvenir of my carelessness.

At the A62, another trans-Pennine route, walkers find “Rambler’s Relief” in the form of five pubs, all within two miles of the crossing. A couple relegate hikers to rather spartan rooms well away from the red velvet plush and horse brass decor. Further down the Colne valley at Linthwaite I discovered a haven for beer connoisseurs at the Sair Inn where Ron Crabtree, an ex-schoolteacher, is one of a handful of British landlords to brew his own ale. Five Linfit beers range from a gentle dark mild all the way up to Enoch’s Hammer, a rich barley wine named after the hammers made by a local blacksmith. These were used in 1812 by Luddite gangs of cloth croppers who resisted the installation of automated shearing frames in the wool mills by smashing them.

“Wool from the hill sheep was the whole way of life on this Yorkshire side of the Pennines, just like cotton on the other side,” Ron told me as we sipped pints of Old Eli (named after his pet spaniel). “Machines meant less jobs and there was no dole in those days. So it was like a real revolution. Government was fighting Napoleon and America at the same time, and they got really nervous about troubles at home. So—they hanged all the ringleaders in York.”

Two young men sitting near the fire overheard the conversation. “Should ’appen be some Luddites round here nowadays. There’s seventy-six of us got laid off last week for’t same reason—automation. Same bloody story all over again.”

Not far from the pub came an unexpected surprise.

A stubby-spired church rose up from a clustering of houses set in fields against a backdrop of stumpy hills and a sky filled with topsy-turvy clouds. Next to the church was a well-dressed field, a level rectangle of velvety grass on which white figures pranced in summer sunlight. Ah!—a cricket pitch—with a Sunday afternoon cricket match in progress. Just the kind of diversion my aching bones needed.

“Owzatsir!”

The umpire in white coat and flat cap standing behind the stumps (three twenty-eight-inch-high sticks topped by two “bails”) agreed that the batsman had indeed been “bowled out” and raised his finger in solemn day-of-judgment fashion. The crestfallen cricketer tucked his beechwood bat under his arm, adjusted his cap, and walked, tall but despondent, to the wooden pavilion. A polite sprinkling of doughy-handed applause greeted him; he’d scored twenty-seven runs in just over half an hour. “Not bad for a young ’un” “Tha’s Tommy Thwaite’s son tha’ knows” “He were daft—he should’ve seen that one comin’” “In’t he t’one as got Sally Atherton into trouble?”…

A young freckle-faced girl in a pretty pink dress ran up to him before he reached the pavilion steps. “Lovely game, darling. Honestly. You were super.” The warrior-batsman smiled wearily…

I love cricket! (Don’t worry, I’m not going to explain it. That’s far too mighty a task for this writer.) I just enjoy the moods of this odd summer institution whose nuances have shaped the great leaders of Britain’s institutions and Empire. That old chestnut “The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton” gives a clue to the importance of the sport in shaping and strengthening the British character.

“It’s not so much a game,” I was once informed by a bristling colonel type at Lords (England’s mecca of cricket in London). “It’s more a way of life, y’might say. It teaches you patience, courage, a little gamesmanship—not too much of that though—fair play, gentlemanly conduct, with a touch of real aggression now and then to assure a win.”

We were watching the fourth day on an interminable five-day “Test Match” between England and Australia. “Patience is perhaps the most important,” he mumbled petulantly as England lost another “wicket” for no additional score.

Back at my own cricket pitch a new batsman emerges to another sprinkling of polite applause from spectators and team (even the opposing side applauds) and the crowd settles down to watch the game again in canvas deck chairs and on old backside-polished benches. It’s a typical village setting—pub, church, pond with random ducks, a cluster of hoary oaks for shade, the clink of teacups in saucers, straw hats, and kids playing tag in the weeds at the edge of the mowed “oval” (I can smell the just-cut grass). A setting untouched by time; a place for manly games and rituals in the warm Sunday afternoon doldrums.

The men in white—white sweaters, shirts, trousers, boots, leg pads—even invisible white groin “boxes” for protection—are trying to bowl, stump, catch, run-out, or otherwise decimate the eleven members of the opposing team for as few “runs” as possible before the end of this one-day match (from 2:00 to 7:00

P.M.

which, by happy coincidence, are precisely the hours during which pubs traditionally close on Sundays!).

It’s a typical country game. Long pauses, then the fast run up by the bowler (balls can exceed ninety mph), the quick click of red ball on blonde bat, the flurry of white flannels as the batsmen scamper to opposite ends of the pitch and score a “single.”

“Good show!” says the vicar, clapping vigorously.

“Nice one that,” says the village bobby, resting on his bike.

“Better start the kettle,” says the vicar’s wife. “Did we get the Eccles cakes from Mrs. Harris? She promised.”

“Go on, Charlie—show ’em, lad,” from the old men in the shade.

The game has hardly begun, following lunch, but the village ladies are already fussing around the table inside the pavilion preparing a gargantuan tea of sandwiches, pork pies, sausage rolls, Scotch eggs, hot crumpets, and cakes with pink icing, all for the men in white.

The casual commentaries from the spectators are a fascinating sublanguage. “Should shift his silly mid-on” “That were a real googlie-ball” “Leg-before-wicket—he’s out!” “Worst third man I’ve ever seen—send him t’long stop” “Move your bloody gully, Charlie!”…

And the game goes on—a duel of enduring dullness with moments of deft marksmanship and cries of “Oh, well played sir!” Spectators doze in the sun. The players all break for tea and then return. One batsman is hit on the shoulder by a high-speed bouncer, and there’s great concern shown by both teams. “C’mon now, lads, play the game right,” mumbles the vicar, upset by such ungentlemanly bowling. Looks like a draw is in the offing; there’s no way the opposing team will be annihilated by 7:00

P.M.

. Plus there’s rain coming. The wind is up and a brief sprinkle dampens the pitch. The umpires agree to “play on,” but a sodden downpour wipes out the match entirely.

“Nice playing lads,” says the vicar, wondering how he could use the vagaries of this afternoon’s game as a telling metaphor in his evening sermon.

“Some pork pies left, love,” offers one of the tea ladies.

“Same time next week then,” says the umpire.

After the storm, I climbed back up the hill out of the tiny village in the middle of nowhere. The path was muddy, my boots were caked in the stuff, and I was hoping for a warm place to stay in that desolate country. It was a shame the match ended so soon, I was just getting into the rhythm of it, dozing, then cheering with the crowd, then dozing again…all in all not a bad way to spend a warm Sunday afternoon in England’s wild heartland.