Back of Beyond (44 page)

“You can always come back,” I said.

Angelo seemed not to hear me and we drove away in silence.

It’s the green you notice at first, particularly the bright sparkling green of the rice paddies between the palms and eucalyptus, and the lacquered leaves of the cashew trees and the frilly fronds of bamboo. Everywhere you look is green, receding into turquoise as the land rises to the jungled hills along Goa’s eastern border. And peeping coyly through the plantations are the shuttered windows of the old Portuguese farms, mansions, and occasional stately palacios, mostly single-storied and set in gardens of flowering bushes. Many have central courtyards, usually with a small fountain where the sound of playing water combined with deep shade offers respite from the summer sun.

Village market stalls brimmed with fresh fruit—coconuts, bananas (from clusters of thumb-sized beauties to the famous foot-long giants from Moira), jackfruit, papaya, pineapples, chickoo, custard apples, and mangoes. And every community, no matter how small, had its own feni distillery producing the araklike liquor that is the lifeblood of Goa. Coconut feni tends to be the most popular—too popular, according to the government, which has seen the export crop of coconuts dwindle to a trickle as farmers leach the sap from fronds where green coconuts should have been maturing in great bunches.

I preferred the cashew feni, which uses the cashew “apple,” normally discarded or used for pig food after the removal of the nut. A widespread cottage industry now exists where locals ferment the crushed apples in battered copper vats, usually in a barn or the back room of a taverna, and distill the heated mash through a crude system of coiled pipes into earthenware jars. The first run is a relatively mild concoction known as

urrack

, which sells for pennies a glass just about everywhere. But connoisseurs await the second distillation, when urrack is mixed with more fermented juice and run through the pipes again to produce the far more potent feni, which is then aged (a couple of weeks is usually considered more than adequate) in four-gallon earthenware jars known as

causos

.

Feni and fry-heat sun don’t mix. A few samples in a village near Margao left me an unusually passive passenger for most of the afternoon.

My awakening came rather abruptly. Our windows were down to catch the cooling breezes as Angelo drove through the narrow streets of a nondescript village north of Chaudi. Suddenly the windshield was awash in colored water—bright splashes of blue and red as little bags burst on the glass. Then they were coming through the side windows. A red one burst on Angelo’s forehead and he looked as though he’d been shot at point-blank range. I opened my mouth to laugh and received a blue one in midchest, which exploded with a pop, spraying my clothes, my notebooks, the inside of the windshield. More followed. We were awash in blue and red.

“The windows! Up!” gurgled Angelo, spitting out the sweet dye.

Too late. More bags whizzed in before we could raise our defences.

I was fully awake now. “What the hell…”

“Holi! Holi!”

“What?”

“It’s Holi—it’s the Shigmo Festival. I forget. They said it had been banned this year.”

We had reached the edge of the village. Our attackers were way back down the road, roaring with laughter, waving masks and colorful cloaks and beating drums. Angelo couldn’t decide whether to be angry or join in the fun. Then he giggled.

“You! You’re all blue.”

“And you, my friend, are very red—and blue.”

“I should have remembered.” He was still giggling.

“What’s it all about?”

“It’s spring. February is the beginning of spring. People sprinkle each other with packets of colored powder—they’re supposed to be flower colors. Spring flowers. Sometimes they mix the powder with water. It’s okay. It washes away.”

I looked in the mirror. My beard, nose, and cheeks were bright blue, not to mention most of my clothes.

Angelo’s giggles had got the better of him. He was becoming quite hysterical looking at me.

“You are a crazy man!”

I looked down. In my lap lay a little bag of blue dye, unexploded.

“Angelo. Look at yourself in the mirror.”

He turned the mirror. I couldn’t resist.

Thwack! I burst the bag on top of his wind-blown hair, and the blue water exploded down his neck, round his eyes, and ran in rivulets down the red dye already coating his face. Now he was purple!

“Two crazy men now.”

We were like kids. He dipped his hands in his streaming face and flicked the spray at my beard. I retaliated. It became a water battle. The inside of the car was dripping with the stuff. We couldn’t stop laughing.

“Happy spring,” he bellowed, spraying me again.

“Happy spring to you too!”

Goa and the Goans take themselves quite seriously in spite of their penchant for enjoying life and smiling all the time. They consider their little country, relatively affluent in Indian terms, to be distinct from, and superior to, most of Asia and the Orient. You can see it in the popular roadside sign:

MORE WORK, MORE FOOD, MORE ELECTRICITY.

LET’S MAKE GOA A LAND OF PLENTY

.

Even the man selling gaudy postcards on the beach by the classy Oberoi resort at Bogmalo seemed far too well dressed and disinterested for the job. As soon as the tourists left, he leaped on his bicycle, combed his black hair, and departed with a professional expression on his face as if he were off to something far more worthy of his time and intellect.

An elderly gentleman in charge of a food concession at Miramar (wonderful Indo-Chinese-Thai concoctions at these places) left the cooking to his young assistant and joined me at my table to discuss the revival of

Life

magazine and the intricacy of British politics.

Goa is a little weary of its image as a cheap haven for freaks and potheads. Beach signs issue strict warnings:

DON’T DABBLE IN DRUGS

IT IS A SOCIAL EVIL AND CRIME

PUNISHABLE WITH 10–30 YEARS IN PRISON

BEWARE OF THE MENACE!

And they remain proud to the point of paranoia about their own language, Konkani. Whatever you do, you don’t call it a dialect. They see it as a distinct and separate language, well over a thousand years old, and once subject to ferocious persecution by their Portuguese overlords.

“It is a perfect language for poetry,” I was informed by a man who ran a newsstand in Margao. “We have many literary prizes for Konkani and many fine writers like Bakibab Borkav, R. V Pandit, Nagesh Karmali—and of course, Manohar Sardesai. But it is a struggle. The Indian government does not encourage its use, so,” he laughed, “we use it even more.”

He showed me a piece of yellowed paper with finely inscribed print in Konkani. He translated:

Into the realm unknown to man

Into the heart unfound on earth

Into the eternity unread in life

“I keep this,” he said, and patted the pocket next to his heart.

While officially Goa is now a part of India, the Goans insist on maintaining their rich cultural identity. Angelo had been correct. There had been efforts made to suppress the celebrations of Holi—“In some places there were some problems last year with protestors and riots, so the government said it must be banned. But Goans don’t like to be told what to do. We are free people—and it must stay that way!” Angelo insisted.

Up north, at Ajuna and even Mandrem and Arambol beaches, you’ll still find the remnants of the flower-power days—defiant freaks, mellowed monks, overlanders, gypsies, poets, guitar pickers, seers, searchers, artists, punks, all dancing, philosophizing, hash-happy under the light of the great silver Goan moon. Maybe one day I’ll go and play hippie-for-a-day or a week or join in the riotous pujas or dance naked with the wild ones. But not this time. I wanted seamless days for a while; no distractions, no diversions. Just me and the sea and the frangipani and a glass of feni and maybe some prawns and fresh fruit picked from wild trees by the beach….

At Palolem, way to the south near the border with the state of Karnataka, I found my paradise, a true “pocket of singular languor”: This was the Goa I had come looking for. The Goa before the world-wanderers and truth seekers arrived. An arc of sparkling sand on a bay no more than a mile wide, bound on the northern edge by a jungle-covered headland that kept the water calm. A village of simple palm-frond-and-bamboo homes, similar to those in Samoa, set under the palm trees; a few fishing boats carved from tree trunks; surf nets drying on the white sand; a tiny taverna with its own feni shed, a plain room where I could stay for a dollar a day if and when I wished; a young girl who cooked the best banana pancakes I have ever tasted and made fresh curry sauce every day, carefully mixing it from hand-pounded spices she kept in little cotton bags.

Angelo had to return to Panaji. He told me I’d have no problem getting back up north when I was ready. In a way I was sorry to see him go. In another way I was delighted to be here alone, not a part of anything and yet feeling to be a part of everything.

Maybe I’ll write a bit. Maybe take some photographs or sketch. Maybe read a little about Syadvada (the sadhu in Bombay had given me one of his own books on Jainism).

Or maybe not…

The days would define their own rhythms—new thoughts, coming and going as they may. Life doesn’t offer too many opportunities like this, even for a travel fanatic like me. Time seemed unimportant. Plans would be remade. Later.

I remembered the little Konkani saying shown to me by the newsstand man in Margao:

Into the realm unknown to man

Into the heart unfound on earth

Into the eternity unread in life

THAILAND’S GOLDEN TRIANGLE

It’s just like moon walking. The last few miles on this almost-invisible jungle path have been relatively free of obstacles and we bounce along on cushiony ground. There was a bad patch an hour or so ago—nothing but creepers, vines, roots, rocks, and nasty little hollows that you couldn’t see until it was too late. San, my guide, has stumbled a couple of times but keeps on smiling (he never stops smiling); my tumbles are rather more regular and my smile is buckled. I have no idea where we are, but the mossy smoothness of the path has mellowed me into “mai pen rai” (“it doesn’t really matter”), a typical state of mind in Thailand.

In the dense, dark underbrush of the teak forest, there are clicks and cracks and crackles, but we don’t see anything. I’ve been bitten all over, but I never see the biters. It’s an odd feeling, to be so intensely part of something and yet to feel aloof, as if I were floating a few feet above my battered body, bemused by the whole effort.

“Soon be coming,” says San. (He’s said that for the last two hours.) But maybe this time he’s right. The jungle seems to be thinning out, and I can see flickers of hills ahead with tiny fields scattered over them.

If someone had told me a couple of weeks ago that I’d be hiking through the notorious “Golden Triangle” of northern Thailand, smack bang in the middle of the world’s most lucrative opium-growing region, I’d have laughed and continued to enjoy the pampering pleasures of Bangkok. But now here I am, within spitting distance of Burma and Laos and the famed Mekong River, doubtless trespassing in some drug warlord’s territory, and being strangely unperturbed by my arrogance. San has warned me about Khun Sa and his army of five thousand ferocious “opium soldiers,” telling me a few unpleasant tales of their penchant for bamboo torture and the casual dismemberment of intruders. “‘S’ okay now. Wrong time for poppies. No problem.”

In contrast to the bright, rich patina of twentieth-century Bangkok and the more affluent southern region of Thailand, the wild hill country of the north hides hundreds, some say thousands, of tiny primitive villages inhabited by tribal migrants from Burma and China who have been easing southward into this wild territory for centuries. The broken, virtually impassable terrain of deep valleys and jungle-clad mountains has allowed the seven basic tribal groupings to retain most of their ancient cultural trails.

It’s an anthropological paradise up here, and courageous observers often venture into this wilderness to study the contrasting mores of the primitive peoples. They compare the desire for “mutual spiritual harmony” of the Karen with the egocentric “me-oriented culture” of the Lisu and the “decorum-at-all-costs” attitudes of the Yao. They are boggled by the contrasts of tribal dress: the dour blacks of the Lahu contrasted with the colorful extravaganzas of the Akha and embroidered richness of Meo costumes. They are intrigued by the wide variety of sexual customs, even among different tribal groups living close together in the same valley. The Karen, for example, believe that one of few appropriate times for courtship is at funerals, whereas the Yao and Meo encourage relatively “free love.” The Lawa have very strict taboos against licentious activities and, after marriage, Akha couples often have to limit their lovemaking activities to a tiny isolated hut raised high on stilts so as not to offend their house spirits or one of the ten thousand “codes of conduct” that govern every aspect of their lives!

Those who take the time and trouble to explore the hill country gain fascinating insights into the way our ancestors must have lived thousands of years ago. And while Thailand’s popular present-day King Rama IX provides modern-day citizens with a treasured link to the country’s rich heritage, the hill tribes are an elusive reminder of far more ancient cultures and origins. In these hills you walk hand-in-hand with prehistory.

The twelve-hour overnight public bus ride north from Bangkok to the hill country was a marvel of modern comfort (they take bus journeys very seriously here). The modest ten-dollar fare included a supper packed in a ribbon-wrapped box, constant refills of Coke with Thai “scotch,” a video TV screen visible from our reclining seats, a stop at 3:00

A.M.

for a second supper (five courses) in a huge roadside restaurant, and personal pampering all the way by three beautiful stewardesses.

We arrived in the northern city of Chiang Mai, Thailand’s second largest city. It was cooler here with a pleasant breeze tumbling down from the hazy hills. I wanted to be off immediately but was told my guide had been delayed. So I agreed to make the ritual round of the city’s famous craft workshops, visiting silversmiths, umbrella makers, silk weavers and teak carvers. I found myself impressed by the skill and patience of the artisans (but annoyed by the “tourist trap” tone of the tour).

Soon Chiang Mai was far behind. I sat happily with San in the front seat of a four-wheel-drive Jeep as we headed for the hills, across the flat paddies where peasants winnowed rice in huge straw baskets, past mud holes occupied by wallowing water buffalos, pausing to buy fresh lychees from a roadside stall, watching villagers fish with a hammock-net (and avoid the local alligator!). We switched to a boat for a journey north up the Mekong River (memories of Vietnam), warily taking photographs of tribal people on the Laos side. Our boat carried the likeness of Che Guevara on its prow, which seemed most appropriate in the circumstances.

Finally we were on our own to find the hill tribes—just the two of us, slogging up steep mountain tracks, going deeper and deeper into the dense jungle, hacking at bushes, skirting fallen trees, crossing turbulent streams, cooking bits of dried chicken and rice on a battered butane stove in the evenings, and sleeping on lightweight plastic sheets spread out on piled leaves.

San always seemed to know where we were going even though he claimed our route as a “first” for him. On the third day we were hardened hikers but we realized we had better watch out for ourselves in the heart of this mysterious Golden Triangle.

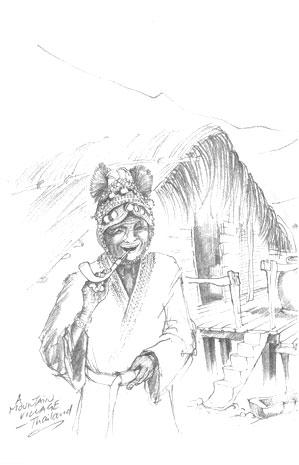

We scrabbled over the next ridge, down into a more open valley where trees had been cleared and small fields were planted with corn and beans. A few men in black trousers and waistcoats sat around in groups watching the women hoe and weed the rows. Higher up a village of large thatch-and-bamboo huts perched on stilts a few feet above the steeply sloping hillside. The place seemed poor and bedraggled. Smoke wafted through the thatch roofs, big pigs waddled around or lay like fat black cushions in dust holes under the houses, children in black pants and skirts watched us curiously. At first no one seemed particularly interested in our sudden arrival, but gradually the children began to cluster and a large stern-faced woman with short-cropped hair approached us, talking staccato fashion in the local dialect. San listened intently.

“She asks to know if we’ve come to buy.”

“Buy what?”

“Opium.”

We both laughed, shook our heads, and San explained politely that we were hiking the hills and taking photographs. Her face became even more stern; she stood straight and pointed to her head (she was obviously used to giving orders).

“I think she wants you to take photo of her.”

So I did. It was not one of my classics though; the subject stood as if defiantly waiting for a final firing squad volley and seemed definitely displeased with us.

Then, wobbling down the hill, came an elderly man in black, carrying an old contraption of bamboo pipes bound together with twine. The stern woman shouted something at him, and he began to play an eerie melody of half tones and quavering minors while a dozen kids danced around him in the dust.

“He plays the ‘Kaen’ for our welcome. They do not understand who we are but they play this for visitors from other villages,” San explained.

I was starving and hoping for an offer of food. But then San suddenly went very still again. He watched the woman talking to two men a few yards away. Something was not right. People were moving in from the fields below and climbing up toward the village.

“David, I think we should go now,” he said quietly. “Smile and hold your hands together and do wai.”

I felt ridiculous but trusted San’s instinct. We walked slowly backward up the hill doing our bobbing wais. The man with the bamboo instrument played louder and louder—it didn’t seem like a welcome at all now, more like a wailing siren echoing in the hills.

“David” said San, “when we get past this house we must run to the trees. Please do this.”-

As soon as we were out of sight we ceased all the wai-ing and scampered into the jungle. It was suddenly cool again as we crashed through the brush following a pig path. We were both panting, and I could hear that strange wailing way back in the village. I knew we had made the right decision but didn’t understand San’s reasons. A long time later, after we had run ourselves to a standstill, he explained between great gulps of air:

“It is my mistake. I missed the sign. They were waiting for someone special. I think they think we are spies—from the government—maybe it was the cameras. And that man was not playing hello on his kaen, he was warning the village about us….”

We panted in unison.

“It’s a good thing we left, San.”

“It is a very good thing. Yes,” agreed San.

A day or so later, what could have been a disastrous expedition turned into a delightful interlude with the Meo tribe. Many long jungle miles away from our dangerous encounters we began to enjoy a more mellowed experience. Hardly had we entered their village than we were made guests of honor at the headman’s house and for a few days were allowed to watch and talk with anyone we pleased about anything that came to mind.

I was amazed by the cleanliness here. In the middle of the jungle, in thatch houses shared with dogs and chickens (and other less domesticated creatures who kept popping in unexpectedly), the women were always washing their hair and sweeping it up into tight topknots, preening their faces, polishing their ornate silver jewelry, hanging out their beautiful hand-embroidered skirts to dry after strenuous washing on rounded rocks, cooking in cast-iron cauldrons on fires at the center of their earth floor inside their homes, and then washing the pots on the steps outside.

No one seemed to have heard of chimneys so the smoke just hung around the house, giving flavor to chunks of meat, corn, and chilies suspended above the fire, and blackening everything else inside. Each surface had a sooty patina but that only seemed to make the urge for cleanliness even stronger.

The headman’s home was the worst of all. His status had enabled him to build some of his walls out of cement block carried by hand for miles from the nearest jeep track. It looked relatively impressive but the concrete only kept more of the smoke trapped inside, with the result that San and I spent most of the time in other split-bamboo-walled houses where there was a chance of breathing more freely.

Here we heard tales of the mysterious Phi Thang Luang, “people spirts of the yellow leaves,” who were thought to be mythical beings haunting the deepest parts of the jungle, until their recent discovery by a jungle expedition. We were also told of the tremendous efforts by King Bhumiphol Adulyadej (Rama IX) and his government to replace opium growing with more useful (but often less lucrative) crops.

One old man with no teeth and crazed smile explained how intricate the January opium harvest used to be. “You must cut each poppy pod correctly—just the right depth—then let the gum drain slowly overnight and then come and scrape the gum with a special knife the next day…” He paused and chortled. “Can you guess how many pods we used to cut? It was very hard work. Corn is much easier!”

Having extolled the virtues of corn at length he lay down on a blanket in a corner of his house and began the slow elaborate process of opium smoking. He placed each round pellet of dark oily substance on a long stick and heated it until it bubbled, then inhaled the smoke through a long bamboo pipe, all the time prodding and pushing it with his thin stick.

His wife seemed unconcerned. “It is a Meo tradition for men. We chew betel instead,” she laughed, exposing the brown-stained mouth and teeth, and then added quietly “…and we do all the work too!” (Emerging liberation tendencies among the Meo?) But then she rose to move a smoking kerosene lamp closer to her prostrate husband as he struggled to light his fifth pellet….

In many of the houses we saw special “spirit shelves” (

dhat-jee-var-neng

) on which sacred objects—bones, horns, dried animal intestines—were placed for animistic worship of the sky, the wind, the forest, and family ancestors. The husband and the eldest son would usually pause in silence at their own shelves before sitting on the earth floor for their evening meal of rice with vegetables laced with ground coriander, chili peppers, and maybe a little chicken or smoked pork (not particularly gourmet fare, but for two jungle bums like San and me, a feast indeed).

Life was simple here, the people open and friendly, and the mood decidedly mellow. There were about twenty rattan-and-thatch houses in the village, sprawled loosely over a hillside deeply etched by water channels (a remnant of the last monsoon season). The headman’s house sat at the top of the rise against a backdrop of dense jungle, which rose layer on layer, like green flames, behind the stockade where he kept his prize pig. The other houses were large structures, each at least thirty feet square, with wide roof overhangs on two sides. Someone was always dozing in their shade. The pace of life in the village (particularly for the men) was pleasantly slow.