Backstage with Julia (30 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

"No!" she bellowed disgustedly. "I'm never going to another one."

"Why not?" I asked, foolishly thinking that the two-hour road trip from Cambridge to Northampton had been too much for her.

"They're all old people!" she said.

When Julia said "old," it had nothing to do with years and everything to do with attitude. Many of her contemporaries had settled into complacent, sedentary lifestyles and she simply could not relate to them. So she gravitated to younger friends who were as active as she wasâor perhaps we gravitated to her because she was as youthful as any of us and a heck of a lot more fun than most. When I look at over twenty years of favorite photos taken at parties, on trips, or at spontaneous get-togethers, there's Julia in the midst of our cozy group of friends, all of whom were much younger. And she always fit in. We never truncated our plans because lunch, then dinner, then a late-night party might be too much for an octogenarian. We didn't temper our words, withhold racy stories, or refrain from telling dirty jokes because they might be offensive to someone born into a less permissive generation. Actually, as I think about it, Julia told more of those stories and jokes than we did.

On the few occasions when something reminded us that Julia was indeed so much older than the rest of us, it actually took us aback.

Just before Julia's eightieth birthday, Susy Davidson traveled with her to France. Their day began with a predawn wake-up call and a live appearance on

Good Morning America

. After taping some additional shows, Julia and Susy spent the better part of the afternoon at a veal-tasting lunch arranged by

Food & Wine

magazine and representatives from the veal board. Then Julia and Susy left for the airport. Susy wrote me an account of their travels.

"We took an overnight flight to Paris, then a taxi to the Gare de Lyon. We were on our way to visit Pat and Walter Wells and Walter had offered to meet us at the station so he could drive us the hour or so to their house. Julia insisted that wouldn't be necessary.

We'd

be fine. But when we arrived at the station, we searched futilely for a porter and had no choice but to lug our suitcases up a huge staircase to the train platforms and then onto the train. Once we heaved everything on the train and got it all stowed, Julia sank down in her seat and sighed, 'I just can't believe there was no one to help us with our bags. What would old people do?' To illustrate, she then pointed to a gray-haired lady sitting in front of us. 'Just look at her. What would she do?'"

Susy told me that it was only when she observed that, except for the color of her hair, the gray-haired woman didn't look so much older than Julia, did it occur to her that Julia had probably been coloring her hair for over forty years.

I had a similar awakening in London when Julia and I were there for a long weekend. A revival of Noël Coward's 1930 play

Private Lives

was in the theater and Julia wanted to see it, mostly because the British-born, flamboyantly risqué American actress Joan Collins was starring. Somehow Susy Davidson rooted up two front-row seats for us to the standing-room-only performance, and Julia was thrilled.

When the lights went up at intermission, I turned to her and asked, "How do you like it?"

"It's good. But I liked the original better. I saw Noël Coward and Gertrude Lawrence in it and they were

very

good."

It took me a minute to wrap my mind around that piece of information. Julia was old enough to have attended a play that starred people who, in my frame of reference, were historical figures. That realization did nothing to alter my sense of Julia's youthfulness, but it heightened my awareness of just how long she had been living.

Even as I write about Julia and age, I can feel her index finger firmly poking into my upper arm and her telling me to drop it, it's not significant. It wasn't to her, and it wasn't to us, but now, looking back, I have to ask myself what it was that kept her so young. Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, "Men do not quit playing because they grow old; they grow old because they quit playing." Julia simply never stopped playing. Throughout her life, she maintained an unflagging passion for her work, a relentless curiosity about everything and everyone, and a constant drive to try new things. "Life itself is the proper binge," she told

Time

magazine when she was in her sixties, and in her eighties, she was as she always had been, insatiable. There were still places she wanted to go, things she needed to do, and, as it turns out, people she wanted to meet.

In the years since my divorce and Paul's placement in the nursing home, Julia and I talked a lot about how sad it was to be alone. She said that we had to keep busy, so we made a pact to be each other's Saturday night date when we had nothing else to do. But this plan was only semisatisfactory to Julia. "I don't think it's good for us to always be seen out with women," she said. "I think we need to find some nice men to go out with." Julia's emotional attachment and daily attention to Paul were as fervent and unambiguous as they ever were, but she wanted to walk into the plethora of events she attended with a man, not a woman, taking her arm.

"I agree, but nice men aren't all that easy to find."

"Well, let's work at it."

She called me less than a week after the "nice men" conversation.

"I won't be available this Saturday night. I found a man." Who knew she meant we should find men right away? I hadn't even made a list of prospects and she already had a date.

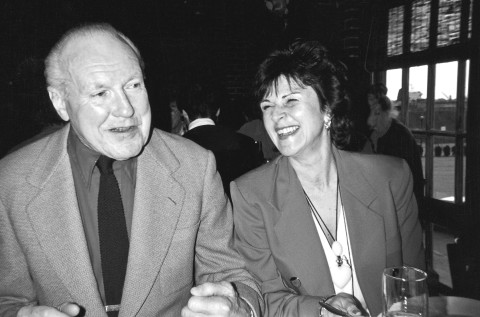

John McJennett was an old friend of the Childs. John's late wife, Toni, had met Paul in 1928 when he crashed her twenty-first-birthday party at her Paris apartment on the Left Bank. Paul, cradling two bottles of claret, knocked on Toni's door and introduced himself by saying, "You're having a party. I think I'd like to come." They kept in touch and renewed the friendship after Toni married John, Julia married Paul, and the two men served in the State Department. John was a few years older than Julia and at least an inch taller. A Harvard graduate, he was smart; a marine who had survived two Iwo Jima landings, he knew well how to tough things out; a former semiprofessional baseball player, he was agile. He was also interesting, dashingly handsome, and one of the nicest men I've ever known. The only thing John was missing was a knowledge of who was who and what was what in the culinary world. One night at dinner, a large group of us was discussing Martha Stewart's latest projects, and for quite a while we shared information about Martha doing this and Martha doing that. John listened patiently and then after several minutes asked, "Who is this Martha chick anyway?"

Having John in her life was good for Julia. There was a renewed spark in her desire to entertain at home. She held more dinner parties and reestablished her annual Christmas cocktail party. As any good friend would be, I was downright jealous, and told Julia so. So she offered to fix me up with another old friend. "We'll have to dust him off a bit," she said. "But he's quite presentable." I declined her offer and instead feigned her can-do attitude and began to find dates on my own, thanks mostly to our friend Sally Jackson, who kept a Rolodex of old boyfriends. But it would be five years and three boyfriends before I met my perfect "nice man."

During the seven months that led to her August 15 eightieth birthday, from New Orleans to San Diego, San Francisco, Napa and Sonoma, Las Vegas, Miami, France, Chicago, and Texas, Julia went at a pace that defied her age, and she entirely ignored what had become the B-word. She considered the milestone irrelevant. The culinary world, on the other hand, was obsessed with it. Beginning weeks before her actual birthday and continuing well into the following year, more than three hundred Julia parties were celebrated, and she appeared at them all. All! As reticent as she was to celebrate her age, the outpouring of affection touched her.

Most of the parties were lavishly produced, extravagantly orchestrated, jolly affairs that were also fund-raisers for causes dear to Julia, so with swelled coffers as an incentive she agreed to take part in them. The Boston television station that had launched Julia's career, WGBH, hosted a party in November at the Copley Plaza in Boston. Luminaries from the worlds of gastronomy, arts, and politics filled the room or appeared on the large portable screen to pay tribute. The Boston Pops paraded into the room playing a piece especially composed for her, "Fanfare with Pots and Pots," with pots, pans, whisks, and wooden spoons. They continued to serenade Julia from the stage, and it was truly amazing how melodious the music was. I guess if the metaphor holds that Julia made music in the kitchen, it follows that the Pops made kitchen in their music. The actress Diana Rigg took the stage and read "Cook and Nifty Wench," a poem Paul had written for Julia's forty-ninth birthday; it was a bittersweet moment. I know Julia wished he were there.