Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients (36 page)

Read Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

Sometimes, when speaking on this topic to hostile industry audiences, I have been accused of protectionism, and wanting to maintain control of diagnosis for doctors. So let me place my cards firmly on the table (it may already be too late). Medicine works best when doctors and patients work together to improve health: in an ideal world, patients and the public would be well informed and engaged. It’s great if they are aware of the true risks in their lives, and informed enough to avoid underdiagnosis. But overdiagnosis is just as much of a worry.

Medicalisation

This whole process has been bundled up under names like ‘disease mongering’ and ‘medicalisation’: social processes, where the pharmaceutical companies widen the boundaries of diagnosis, to increase their market and sell the idea that a complex social or personal problem is a molecular disease, in order to sell their own molecules, in pills, to fix it. Sometimes disease mongering can feel solid, and outrageous; but sometimes it falls apart in your fingers; because despite the marketing games, these tablets might well do some good. Let me walk you through my changeable thoughts.

There’s no doubt that marketing has an impact on uptake of medicines, or that companies try to sell mechanisms that benefit them, and widen markets. We’ve seen that much already, with the depression checklists and the story of serotonin. Psychiatry, of course, is particularly vulnerable to such marketing devices, but the problems extend way out, into ‘unstable bladder’ and other syndromes. To my mind, this process reaches its pinnacle in an advert for Clomicalm: ‘the first medication approved for the treatment of separation anxiety in dogs’.

Often the diseases used have existed forever, but have been neglected, unused, until reanimated by a pill. Social Anxiety Disorder, for example, is at least a hundred years old, and you could argue that Hippocrates’ description of crippling shyness from 400 BC describes it pretty well too: ‘Through bashfulness, suspicion, and timorousness, he will not be seen abroad…He dare not come in company for fear he should be misused, disgraced, overshoot himself in gesture or speeches, or be sick; he thinks every man observes him.’

Generally, people used to feel this problem was ‘rare’: in the 1980s the prevalence was stated at 1–2 per cent; but within a decade estimates as high as 13 per cent were being published. In 1999 paroxetine was licensed for social anxiety, and GSK launched a $90 million advertising campaign (‘imagine being allergic to other people’). Is it good if stressed students can get better at giving presentations in their classes? I think so. Do I want that to happen with a pill? I guess it depends on how effective that pill is, and the side effects. Is it good if lots of shy people believe they have a disease? Well, that might reinforce negative self-beliefs, or it might improve self-esteem. These are hugely complex issues, with profit and loss on both sides of the equation.

The same quandaries arise with the aggressive ‘disease awareness campaigns’ for erectile dysfunction, when drugs like Viagra were being developed. This is something that a lot of doctors probably didn’t take seriously enough before there was a pill to treat it. I suppose I might prefer it if patients were being offered, maybe, ‘sensate focus’ therapy before an erection pill. Moreover, I would prefer that this had always happened, for a long time before Viagra was invented, but there you go: jobbing sex therapists – despite having a very telegenic job – aren’t glamorous enough to raise awareness of their services to the same degree as a $600 billion industry.

The point, I think, is that we shouldn’t walk away, believing that crippling shyness, or disappointment with your sex drive are non-problems, or even that they are unfixable. But, if only for our collective self-worth, we do need to reassert our awareness that there are covert commercial processes beavering away behind the scenes, manipulating these new cultural constructs.

Perhaps the most complete illustration of this phenomenon – the ‘hidden hand’ in the culture of medicine – is ‘Female Sexual Dysfunction’. This was devised in the 1990s as a new way to sell drugs like Viagra to women, and we can trace its rise, and then its subsequent modest fall from grace, over the following two decades.

In the beginning – as is standard – the scale of the problem was overhyped, through a long series of studies and conferences conducted by people who were paid by the pharmaceutical industry. The most widely cited figure for the number of women suffering from Female Sexual Dysfunction comes from 1999: according to this, some 43 per cent of all women have a medical problem around their sex drive.

27

This survey was published in the

Journal of the American Medical Association

(

JAMA

), one of the most influential journals in the world. It looked at questionnaire data asking about things like lack of desire for sex, poor lubrication, anxiety over sexual performance, and so on. If you answered ‘yes’ to any one of these questions, you were labelled as having Female Sexual Dysfunction. For the avoidance of any doubt about the influence of this paper, it has – as of a sunny evening in March 2012 – been cited 1,691 times. That is a

spectacular

number of citations.

At the time, no financial interest was declared by the study’s authors. Six months later, after criticism in the

New York Times

, two of the three authors declared consulting and advisory work for Pfizer.

28

The company was gearing up to launch Viagra for the female market at this time, and had lots to gain from more women being labelled as having a medical sexual problem. Ed Laumann, lead author on the 43 per cent paper, seemed rather haunted by this exposure, and has been much clearer about caveats in his subsequent work. That is a wise move, because it seems to me that if your model says nearly half of all the women in the world have sexual problems, then the problem lies with your model, and not with the women you are describing.

Can we make any sense of such an insanely high figure? Subsequent research has tried to make a better fist of things. A 2007 survey, for example, compares different methods of measuring the prevalence of these problems in four hundred female attenders at a GP practice (already a sicker group of people than the general population, but we’ll continue nonetheless). Looking crudely at the symptoms and behaviour that these women reported, and then comparing them against the list of symptoms in the World Health Organization’s ‘ICD-10’ diagnostic manual (which is used only as a guide to diagnosis, not as a bible or checklist) 38 per cent had at least one diagnosis of sexual dysfunction. But if you restrict this – much more sensibly – to the women who perceive themselves as having a problem, this prevalence falls to 18 per cent. And if you restrict it further – again sensibly – to those who regard the problem as even moderate or severe, the prevalence is just 6 per cent.

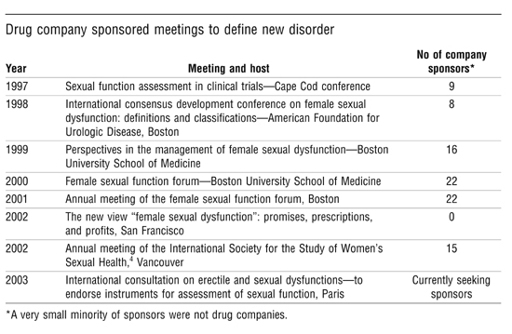

These prevalence papers were not the only tool in the industry’s armoury. There were also conferences – many conferences – all of them well funded. A researcher called Ray Moynihan unpicked this story as it arose, over a decade ago, and has attracted some interesting attacks for his trouble. His list of conferences from 2003 (above) tells a story all by itself.

29

Moynihan’s paper in the

BMJ

was read by a lot of people, and helped raise awareness of this growing problem. Shortly afterwards, patient organisations found themselves receiving a rather strange email from Michelle Lerner, senior account manager at HCC De Facto PR. Moynihan had questioned whether FSD exists at all, she wrote:

I know many support organisations have been incensed about these claims, and we think it’s important to counter them and get another voice on the record. I was wondering whether you or someone from your organisation may be willing to work with us to generate articles…countering the point of view raised in the BMJ. This would involve speaking with select reporters about FSD, its causes and treatments.

Lerner initially denied any involvement with these emails. Then she admitted they came from her, but refused to say who was paying her agency. Finally it was established that she was working for Pfizer, which was – as we know – testing Viagra for women at the time. When it was contacted, Pfizer described this kind of PR activity as ‘customary and unremarkable’.

30

More customary and unremarkable activity was to be seen in the promotion of online teaching materials around this disease.

31

The world of ‘continuing medical education’ for doctors is, as we shall shortly see, a major focus for covert promotional activity. One clear illustration of how free training for doctors can be used to change the emphasis of medical practice was the online resource femalesexualdysfunctiononline. org. This website contained teaching resources on FSD, helping doctors to find people who would benefit from treatment, and it was sponsored by Procter & Gamble, which at the time was developing testosterone patches, hoping to sell them as a treatment to increase women’s libido, and planning a $100 million marketing push to raise awareness of FSD.

32

The teaching programme at femalesexualdysfunctiononline.org was accredited by the American Medical Association, as they so often are, but my concern is not so much what this website says, but rather what it does not: because now it says nothing at all. P&G failed to get a licence to market testosterone patches for female libido, so this apparently valuable, accredited teaching programme for doctors fell off the internet altogether. If we believe that FSD really is a serious medical problem, affecting large numbers of women, then this freely accessible and lavishly produced educational material is presumably a valuable resource. If we believe that the pharmaceutical industry produces these resources for the better education of doctors, without seeking to influence their practice, as they claim, then surely we would expect it still to be online (since the costs of keeping a website up, once it’s been built at great expense, are almost negligible). Instead, it seems that as soon as there’s no money to be made, these educational resources have simply disappeared. That tells a story that will recur in the rest of this chapter: information that sells drugs is given a platform; information that does not is on its own.

That’s not to say, however, that P&G didn’t try hard to get its product licensed, and in the EU it had some success, after a fashion. Medicines regulators know all about ‘off-label prescribing’; they know that when they approve a drug only for use in one narrow condition, or in one small group of people, that caveat can be ignored in practice, as doctors prescribe the treatment for use much more widely, and in many other conditions. Sometimes the regulators can see this coming, and try to head it off. So, in the EU, testosterone patches were approved for the treatment of poor libido, but only in women with diagnosed sexual problems that had arisen as a result of surgically induced menopause (that is, having had their ovaries and uterus removed because of cancer, or something similar). Inevitably, these patches are now being used ‘off-label’, for women without any history of such surgery. The FDA saw this coming a long way off, so it declined to license the product at all, specifically citing concerns about off-label use after the approval committee’s unanimous ‘no’ vote.

33

This might be a good moment to mention that the evidence for testosterone patches being any use, even after surgery, is extremely weak, from two trials in very unrepresentative ‘ideal patients’, showing marginal benefits against a massive placebo effect, with common side effects (sometimes apparently irreversible), and no long-term safety data.

34

It’s worth noting that almost no treatments for FSD have come to market, and crucially, all of the disease-mongering activity we have seen happened in the lead-up to their approval. This was simply the academic groundwork in the companies’ ‘publication planning’ programme, where they prove that a problem is widespread, and create a desire for a cure.

So, medicalisation is a mixed bag. We may well find new safe and effective drugs for conditions most of us have never thought of as medical problems before, and they may well improve people’s quality of life, in all kinds of different ways. There might also be an interesting conversation over where these stand on the continuum between medical treatments and recreational drugs. But these possible benefits come at a cost. It’s clear that we can be distracted in medicine by looking where the money tells us to look, and so miss things: the complex personal, psychological and social causes of sexual problems, perhaps, while focusing on the mechanics and the pills, the ‘impaired clitoral blood flow’ and the twenty-four-hour blood-hormone profiles. We might also suffer a cultural cost when we medicalise everyday life and promote reductionist, molecular, mechanical models of personhood. Similarly, as with size-zero models, when we invent seductive new norms of sexual behaviour, we risk making perfectly normal people feel inadequate.