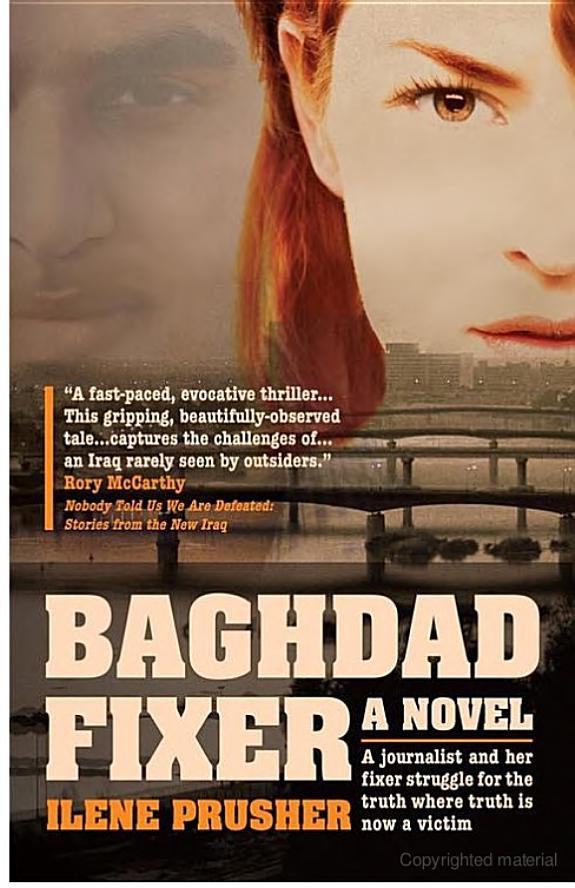

Baghdad Fixer

| Baghdad Fixer | |

| Prusher, Ilene | |

| Halban Publishers (2011) | |

| Rating: | *** |

| Tags: | Contemporary |

A journalist and her fixer struggle for the truth where truth is now a victim

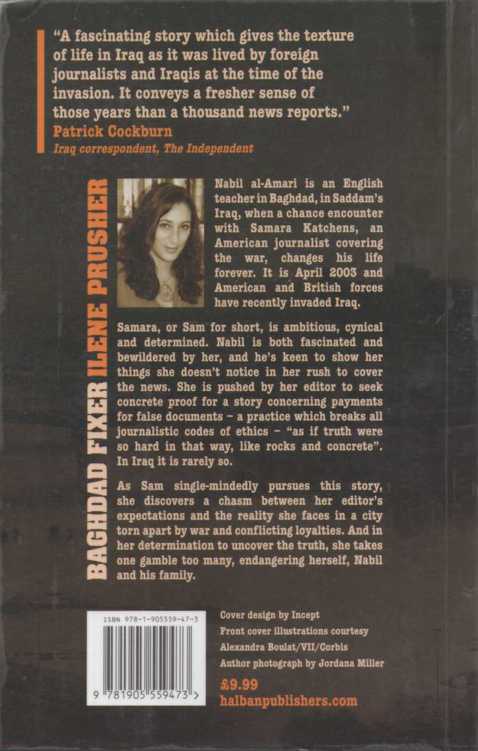

Nabil al-Amari is an English teacher in Baghdad, in Saddam's Iraq, when a chance encounter with Samara Katchens, an American journalist covering the war, changes his life forever. It is April 2003 and American and British forces have recently invaded Iraq. Samara, or Sam for short, is ambitious, cynical and determined. Nabil is both fascinated and bewildered by her, and he's keen to show her things she doesn't notice in her rush to cover the news. She is pushed by her editor to seek concrete proof for a story concerning payments for false documents - a practice which breaks all journalistic codes of ethics - 'as if truth were so hard in that way, like rocks and concrete'. In Iraq it is rarely so. As Sam single-mindedly pursues this story, she discovers a chasm between her editor's expectations and the reality she faces in a city torn apart by war and conflicting loyalties. And in her determination to uncover the truth, she takes one gamble too many, endangering herself, Nabil and his family.

Ilene Prusher was a staff writer for

The Christian Science Monitor

from 2000 to 2010, serving as bureau chief in Tokyo, Istanbul, and Jerusalem and covering the major conflicts of the past decade: Iraq and Afghanistan. Her work has been published in many major US and UK newspapers, including

The Guardian

,

The Financial Times

,

The Washington Post

and

The New Republic

. She is now an independent journalist in Jerusalem, teaches Reporting Conflict for NYU-Tel Aviv, and runs creative writing workshops.

Baghdad Fixer

is her first novel.

~ * ~

BAGHDAD FIXER

Ilene Prusher

No copyright  2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

2013 by MadMaxAU eBooks

~ * ~

1

Moving

My mother says that I am an extraordinarily good catch — handsome, smart, employed. My father doesn’t say anything. And though the timing would seem preposterous to some, we Iraqis have done stranger things in the middle of a war than agree to go on a date.

These dates, if you could call them that, given that we have both sets of parents present, would seem bizarre to a Westerner. But my parents, modern as they are in many respects, are always arranging them: meetings at the homes of well-heeled acquaintances, of my father’s colleagues from the hospital, of second and third cousins I’ve never met. They all have something my parents want: an unmarried daughter in need of a husband.

The women bear common characteristics. I know her profile before I’ve met her. She is in her mid-twenties, even occasionally over twenty-five, attractive enough, and decently educated. She is younger than I am, but is considered to be getting old for this game; with each passing month she is less marriageable. She has never lived anywhere but under her father’s roof. She’s never had a boyfriend, or so her family says.

Noor is not much different, although she is working on a master’s degree in psychology, which is commendable. Unlike me, she’s never had any international experience. I doubt she speaks English, German or French, but she’s considered to be quite clever, Mum says, and rather pretty. It’s not like I didn’t notice that, which is why I agreed to a second “date”, the first having been a cup of tea with her — and her brother Adnan — at an upmarket café next to the University of Baghdad. The air raid sirens went off, so we had to cut it short.

Most importantly, I know my parents would be very happy to have the family of Dr Mahmoud al-Bakri, Baba’s old friend from medical school, as our in-laws. And so it can’t hurt to agree to a second date.

That’s where my tale ought to begin, for those of you who are joining me now, in this, the twenty-eighth year of my life, on the eighth day of the month of April in the year 2003, on the fifth day of Safar in the year 1424. You’ll find me here in the Hurriyah neighbourhood in the city of Baghdad, my beloved birthplace, ill-at-ease and feeling foolish, sitting on this sky-blue sofa with my parents. We’re facing a matching sofa, upon which Noor al-Bakri and her parents sit. I sip tea from their good porcelain cups and hope to avoid eating yet another stuffed date biscuit made by Noor’s mother with great care. If the mother knows how to bake a good

kalijeh,

we assume the daughter will, too.

Should I just say yes? It’s as if they’ve all proposed to me and I’ve told them I don’t yet know. I haven’t made up my mind. I’ll let you know in the morning.

Noor’s mother tries to get me to take one more, and when I decline, she gestures to Noor, then glances in the direction of the fruit on the coffee table that sits between us. Noor rises and then kneels at the table, takes two apples out of the bowl and proceeds to slice them as elegantly as possible. Before I can say no, she lays the pieces out neatly on three small plates. We watch as she cuts into a bright-orange persimmon, and I am thankful when my father breaks our nervous focus on Noor’s fruit-fixing skills by asking Dr Mahmoud whether he’d heard that Dr Abdel-Majid did not show up for work today.

“The psychiatric ward will be bouncing off the walls without him,” Baba says. Dr Mahmoud’s face cracks into a half-smile, the kind a person makes when they’re not sure whether it’s safe to laugh. Mum elbows Baba gently in the arm. Noor’s mother’s face goes blank. Apparently, Dr Mahmoud hasn’t let her in on the office humour. “Dr Abdel-Majid” is a nickname for Saddam that my father and his doctor friends made up. Many people don’t make the connection. The president’s full name is Saddam Hussein Abdel-Majid al-Tikriti. We took him on and put him in charge of the lunatic asylum years ago, the doctors joked. It was a bad move.

When you’re never sure who is listening, you speak politics in code.

Noor, too, seems unaware of my father’s news update: that Saddam has disappeared. Her concentration is locked on attractively arranging the fruit she is expected to serve us. She collects the three plates and rises carefully. Her dark, kohl-lined eyes dart at me, and then back down at the fruit. Her hands are shaking. Despite myself, despite my private conclusion that I cannot marry Noor — and I conclude this within five minutes of meeting most Iraqi women, so at this point I’m only here to indulge my parents’ desire to find a wife for me, to assuage their fears and to allow them to feel that they’re at least doing something to get me married off — I find myself feeling softened by Noor’s deep eyes and her jittery hands, wondering if I should just say yes. She’s earning a masters degree in psychology, after all. But at this moment, her marriage prospects will be reduced to her beauty and to how gracefully she serves us tea and fruit, and it all seems horribly unfair. She does have a pretty face, even if only in an ordinary Iraqi sort of way. She comes from a good family. She’ll make a perfectly decent wife, I’m sure.

Noor’s face freezes and she looks as if she will scream. She pulls in a gulp of air with a sharp squeak but never pushes it back out. Her mouth is locked in a small “o”, her dark eyes scrunch in on themselves like she’s heard a story she doesn’t believe. My mind rewinds to replay the sounds of the moment before, when I was lost in my deliberations, and this time I catch it: the distant pops, the whizzing noise, the fast plink of glass being broken. The echo and bounce and shatter. The eerie calm before the panic.

By the time I catch up to now, Noor has collapsed at our feet, making choking sounds. The red is seeping through the neckline of her

crème

-coloured blouse. For a second, or an eternity, there is an absence of sound. Fruit and bone-china and blood scatter across the floor, on my lap. A sliver of persimmon clings to Baba’s shirt. Noor’s mother screaming.

“

Rahmet-Allah!”

“Where did it come from?”

“Get an ambulance!”

“Goddamn Americans!”

“Where did it go in?”

An air raid siren wails like an injured beast, but it’s dull compared to the shrieking. Her mother’s, my mother’s, Noor’s younger sister’s, conflating with the commotion of a few neighbours bursting into the living room, including Noor’s brother Adnan, who lives next door with his wife. Dr Mahmoud’s mouth keeps opening but no sound comes out, as if he — rather than his daughter — was struck by something in the back of the head.

Baba is already in motion, has long since run and grabbed a towel from their guest bathroom and is pressing it to the back of Noor’s neck.

“Y’alla,”

he yells, “has someone called the ambulance?” He shakes his head.

“Makufaida,”

he says under his breath. No way. No point. No chance it can end well. I don’t know if that’s Baba’s diagnosis, or just disbelief.

Noor’s mother is in the kitchen, pressing frantically at the telephone. I look in on her and she lets the receiver fall to the floor. Her lips tremble and she begins to bawl. “There’s no dial tone!”

“Leave it,” Baba calls out. “We’ve got to get her into surgery. We’ll take her ourselves. Nabil? Nabil, for God’s sake, are you with me?”

I start ordering anyone in the house who is coherent to help me get Noor into our car. Of course there’s no dial tone; most phones have been dead for a fortnight. And what are the chances of getting an ambulance here in time? The city has been under bombardment for more than three weeks. Bombs are shattering buildings to bones, aircraft are strafing entire neighbourhoods, shells are picking away at the very flesh of the riverfront. Who’s going to send out an ambulance to save one girl?

Adnan and Baba and I carry Noor into my father’s car and lay her down on the back seat. Baba tells Noor’s mother to stay at home with her younger daughter, who is convulsing with hysterics, and to cover poor Dr Mahmoud with a blanket. There lies on the floor Baba’s old school friend, the oncologist, a fast-ageing man who has become accustomed to the slow, manageable death of strangers. Not the shooting of his daughter through the window of his own living room.