Ballet Shoes for Anna (17 page)

Read Ballet Shoes for Anna Online

Authors: Noel Streatfeild

“I think it was then Gussie saw the horse. As it seemed then it appeared to have gone mad, but I know now the horse knew just as the birds had known what was to happen, it was

only us who did not know.”

“Then it happened?” Madame Scarletti asked. Francesco nodded.

“In the camp, men asked us often how it was but we could not say. Now I can remember a great noise and hot air, then the earth moved and we were thrown everywhere. Afterwards we got to the top of the hill and looked. All was gone. The little house, Jardek, Babka, Christopher, Olga and Togo, as if they had never been.”

Madame Scarletti seemed to know the end of the story.

“Then Sir William Hoogle found you and soon he discovered your uncle and your aunt with whom you are now living.”

That was when Anna joined in. “They are not nice. The Uncle thinks to dance is wrong.”

Francesco tried to be fair. “The Aunt tried to be kind but she is afraid of The Uncle. When S’William comes back I hope he will arrange things better.”

Madame Scarletti beckoned to Anna. “Go to the barre and we will see what you have learnt.” Then she smiled at Francesco.

“There is good news for you. Sir William has arrived in England.

The Times

newspaper printed this. Now he is home I believe you can be a little boy again.”

M

ADAME

S

CARLETTI HAD

a car. She told Maria to drive the children to the station and to see them on the right train.

“I shall write to Sir William,” she told Francesco, “and arrangements will be made for Anna. It may be she will live here with me.”

These words were like a Te Deum to Francesco. Madame would write to Sir William. Madame would make all the arrangements. Madame might even have Anna to live with her.

Because of being taken by car to the station, the children were home in good time, but Gussie was home before them. He had felt annoyed at this, for he wanted to tell them about a film he had seen on TV and he must do it before supper, for the last thing he wanted was Francesco and Anna being late going to bed. If he was to wake up in the middle of the night he should go to sleep early.

“Where have you been?” he demanded.

“To see Madame Scarletti,” said Anna.

Anna spoke in so pleased a voice it maddened Gussie.

“And what for? Who is to pay for lessons in London?” Then he turned to Francesco. “Why did you let her go? It had been hard to get fifty pence for that Miss de Veane, to get enough for Madame Scarletti and to get Anna to London is impossible.”

Francesco was too happy to mind what Gussie said.

“Imagine! S’William is in England. It is in

The Times

newspaper. Have you been to the farm to put Bessie and the hens to bed?”

Gussie would have loved to say “Yes, I have!” but he couldn’t. Rushing home to tell the others about the television he had seen and the food he had eaten he had forgotten the farm in his annoyance at finding the other two out.

“No. But I will go now.”

“Both will go now,” said Francesco. “If we run we should not be back late for supper. But if we are, do not worry, Anna, keep saying ‘S’William is back’, then nothing The Uncle says will matter.”

The boys ran all the way to the farm. It was dark when they got there so the hens were waiting to come into their coop. Bessie, of course, could get into her sty but there was a padlock on her door at night, the key of which was kept under the grating with the house key. Wally had lent them a torch.

“If S’William answers my letter soon,” Francesco said, “have you a plan? I mean, we know about Anna but what

about us? What do we want if the picture sells for much money?”

“I do not wish to live with The Uncle,” said Gussie.

“I do not wish either,” Francesco agreed. “But where else do we wish to go?”

Gussie fixed Bessie’s lock.

“If it was possible I would like a caravan. Not of course as before – that can never be – or perhaps a little house like Babka and Jardek had, but I do not think that is possible in Britain. There will be police and laws about children living alone.”

Francesco held out his hand for Bessie’s key and turned the torch on to the grating.

“The only rule in Britain that we know is the one of which Christopher always spoke. Do you not remember how, if we made an extra noise when he was working, he would say ‘I will have hush. If you kids lived where I was brought up I’d refuse to keep you, then they’d clap the lot of you into a home’?”

Gussie felt a sort of heave in his inside.

“Suppose The Uncle did not want us. Could he put us in a home?”

“Not unless we did something bad. But he does not have to have us. You remember how The Aunt said: ‘He does not like children so it is hard for him that you are here, but he does his duty, he gives you a home.’ ”

Gussie, wondering if painting a gnome was so bad you could be clapped in a home said:

“And you said: ‘We did not ask to come.’ ”

Francesco put away the keys.

“We are not going to do anything bad, but it is good that when we see S’William we tell him where it is we wish to live.”

Gussie did not say much on the way back to Dunroamin. He wished now he had not agreed to paint a gnome blue, especially as there was no money in it, but it was too late now to do anything about it.

It had seemed to Gussie that evening that Francesco was never going to sleep. He was so excited about S’William coming home he had to talk about it. At last Gussie in desperation pretended to be asleep, in fact he pretended so well he was almost asleep when something reminded him of what he had to do. He sat up in bed and looked towards Francesco’s bed. He certainly did seem to be asleep. Very quietly, Gussie slipped out of bed. The window was already open so, fixing a loop of the length of string Wilf had given him round his left big toe, he dropped the other end, which had a small weight on it, out of the window, got back into bed and promptly fell asleep.

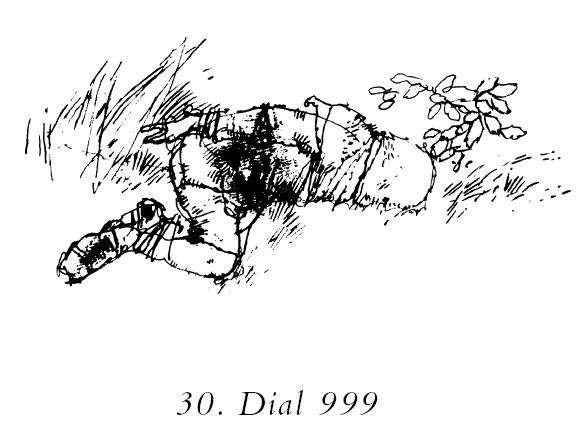

What seemed to Gussie hours and hours later he was woken up by a continual tugging at his left toe. For a moment he could not remember what was happening, then it all came back to him. He felt down the bed for the string, took the loop off his toe, gave three tugs of the string as Wilf had told him, put on his dressing-gown and bedroom slippers and sneaked down the stairs. Very quietly he opened the

lounge door, fumbled his way across the room to the French windows, unlocked them and he was in the garden. There he heard Wilf say “This is ’im.”Then a sack was put over his head and he was rolled over on his face. Then once more he heard Wilf’s voice.

“Now you lie still and nothin’ won’t ’appen to you. But if you tries anythin’ you know what to expect.”

Gussie, tied inside the sack, could not draw his finger across his throat but he knew all right. Just for a few moments he was puzzled. He expected to hear whispers and perhaps the movement of a pot of paint. He could not imagine why Wilf had tied him up in a sack instead of letting him paint one of the gnomes. Then a new thought came to him. Why was there no sound? Why did nobody move about, not even to give him a kick? The horrible answer soon came to him. The Gang were not wanting to paint a gnome. They had got him out into the garden so that he would leave the French windows open. They were going to steal from The Uncle.

The sack was uncomfortable and dirty but there was plenty of air inside it so Gussie could breathe. He rolled over on to his back and thought what to do. If he called for help Wilf and his friends would stop him, and anyway muffled in a sack The Uncle wouldn’t hear, sleeping the other side of the house. But Gussie was agile as an eel. He rolled up and down the concrete paths, which pretended they were crazy paving, and at last he was rewarded, the rope which had held his arms to his sides shifted to his feet. Then it was a matter of seconds for Gussie to sit up, push off the rope and wriggle out of the

sack. Then what? He could not shout for help for The Gang members would hear. Then he had an idea. On his hands and knees he crept up to the lounge door and peered in.

There seemed to be three of them – Wilf and two others. Wilf was holding a torch and the other two were trying to open a safe let into the wall. Gussie did not know it was a safe but he could hear what they whispered to each other. A rough voice growled:

“You never said that ’e kept the money in a safe, Wilf.”

Wilf didn’t sound his tough self at all, in fact he almost whined.

“I didn’t know, did I?”

A third voice said:

“Better give it up. We ’aven’t the tools to open that.”

“ ’Oo says we ’aven’t?” the rough voice retorted. “I never bin beaten by a safe yet and this should be dead easy.”

While they were talking Gussie had got to his feet. Very quietly he took the key out of the inside of the lounge door. Then softly he shut the door and locked it on the outside. Then he ran to the twins’ wall and yelled:

“Help! Help! Thieves!”

He made such a noise that both twins woke up and shoved their heads out of their windows.

“Who is it?” Jonathan asked.

“It’s me, Gussie. How is it when you need policemen? There are three thieves in the house.”

It seemed no time after that before sirens were blowing and policemen all over the place. In most houses Wilf and his

friends would have got away, but they did not know Cecil. The locks and chains on his front door were splendid, so Wilf and his friends were caught red-handed.

When the thieves, including a very cowed-looking Wilf, had been driven to the police station, the police sergeant who was in charge asked everybody to come into the lounge, including Mr Allan and the twins as well as Mabel, Francesco and Anna. By that time it was established that nothing had been stolen and no one had broken into the house.

“Now,” said the police sergeant looking at Gussie, “you say you were in the garden. Had you left the French windows open?”

Gussie’s thoughts were running around like a cage full of mice.

“Yes.”

“So you let the thieves in. Did you do it on purpose?”

“No. I was tied in a sack.”

“But what brought you down into the garden in the middle of the night?”

Gussie felt there was nothing for it but the truth.

“I was to paint a gnome blue.”

“Disgraceful!” said Cecil.

“Paint a gnome blue!” The sergeant was puzzled. “I’m afraid you want a better story than that.”

That annoyed Gussie.

“It’s true. I was to paint a gnome blue.”

The sergeant sounded very unbelieving.

“You were meeting the thieves to paint a gnome blue.

Then you know who they were.”

Too clearly Gussie could hear Wilf making a gurgling sound and drawing his finger across his throat.

“Only one and I can’t tell you his name.”

Priscilla tried to help.

“We know one of them. He’s Wilf who goes to our school.”

In a very angry voice, Cecil said:

“I’m afraid you’ll get no help from my nephew, Sergeant. Result of a bad upbringing.”

None of the children was standing for that. Francesco said:

“No one shall say we had a bad upbringing. It was a beautiful upbringing before the earthquake.”

“Beautiful,” Anna agreed. “It is only now that Gussie does something bad – never before.”

Gussie was furious.

“I don’t see that I have done something bad now. It was me who got out of the sack and shouted to the twins to send for policemen, and it was me who managed to lock the thieves in. If I had not done that they would not have been caught.”

The sergeant looked at the constable, who was taking notes.

“Take a torch and go out into the garden and see if you can find a sack and a length of rope.”

While the constable was gone Mr Allan said:

“I must say, Sergeant, if what the boy says is true – and I

suspect it is – I should think he ought to get a reward. It was a stout effort getting that key out of the door, for if the thieves had caught him I hate to think what might have happened.”

Before anyone could answer, and it was clear from the furious look on Cecil’s face that he was going to, the constable was back with the sack and the rope.

“There,” said Gussie, “you see, I was telling the truth.”

Gussie looked almost fat with pride. It was more than Cecil could bear.

“If the sergeant has done with you, go up to bed, Augustus. I will deal with you in the morning.”

“And you go too, dears,” Mabel told Francesco and Anna. “I will be up with hot drinks for you all in a minute.”

Cecil almost roared.

“Not for Augustus.”

Then a very odd thing happened. Mabel, looking more than usually held together, this time by the sash of her shapeless dressing-gown, with her hair not falling down but meant to be down, puffed out:

“Augustus needs a hot drink more than the other two. He has been out in the night air in his dressing-gown, and he is certainly over-excited, which well he may be for, as Mr Allan said, he has been a very brave little boy. So if you will excuse us, Sergeant.” Then, without looking at Cecil, she swept the children in front of her and marched out of the lounge.