Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (9 page)

However, Collins’ fielding ability, according to those who saw him play, was unparalleled by any of his time. He is said to have been the first to charge bunts and play them barehanded, and, in 1899 and 1900, he set records for chances (593) and putouts (251) by a third baseman (both of which were broken in later years). He was also a good hitter, having led the National League with 15 homers in 1898, and also having driven in more than 100 runs twice, and batted over .300 five times during his career. While those numbers may seem modest by modern standards, they were actually considered to be rather impressive during Collins’ time. And, when taking into consideration his reputation as a fielder, they are probably just enough to justify Collins’ selection to the Hall of Fame.

Ray Dandridge/Judy Johnson

Although the statistics that are available for both Dandridge and Johnson are extremely limited, the reputations of both men suggest that they were exceptional players. Also, seeing as how both were generally considered to have been among the ten greatest players in the history of the Negro Leagues, it would seem that Dandridge and Johnson are deserving of their places in Cooperstown.

Ray Dandridge is considered to be, by those who saw him play, one of the greatest fielding third basemen in baseball history. In fact, although he played during the 1930s and 1940s, his fielding has often been compared to that of Brooks Robinson, although, it is said, he had a better arm. Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, who played against Dandridge in the Negro Leagues, said of him, “He had the quickest reflexes and the surest hands of any infielder I’ve ever seen. In a season, he had a bad year if he made four errors.”

Dandridge was also an excellent contact hitter, compiling a lifetime .335 batting average in Negro League competition, hitting a career-high .370 in 1944, and hitting .347 in exhibition games against major league pitching during the course of his career.

Speaking of the righthanded hitting Dandridge, Irvin said, “Most of his career, he batted in the number two position because he made real good contact and could hit the ball like a shot to rightfield on a hit-and-run situation.”

All things considered, Dandridge probably deserves to be ranked among the ten greatest third basemen in baseball history, and possibly in the top five.

Judy Johnson, as Pittsburgh outfielder Ted Page said in

The

Official Negro Leagues Book

, “…was a scientific ballplayer who did everything with grace and poise. You talk about playing third base, heck, he was better than anybody I saw—Brooks Robinson, Mike Schmidt, or Pie Traynor.”

Although known more for his defense, Johnson was also a consistent .300 hitter who was renowned for his cerebral approach to the game. His baseball acumen eventually landed him a job as a major league scout, and he is credited with signing Richie (Dick) Allen while scouting for the Phillies and outfielder Bill Bruton when he was a Milwaukee Braves scout.

While, in all probability, Johnson was a worthy Hall of Famer, he doesn’t seem to have quite the credentials of Dandridge. Even with the limited availability of statistical data surrounding Negro League players, it appears that Dandridge was the better hitter, and he was probably at least the equal of Johnson defensively. Therefore, the logical question that follows is: Why was Johnson elected to the Hall of Fame by the original Negro Leagues Committee in 1975, while Dandridge had to wait until 1987 to be elected by the Veterans Committee? The most likely reason is that Johnson was a member of that Negro Leagues Committee and Dandridge was not.

Jud Wilson

Generally rated right behind Ray Dandridge and Judy Johnson among Negro League third basemen was Jud Wilson, who played for four teams over the course of his 24-year career. Though not as strong defensively as either Dandridge or Johnson, Wilson was the best hitting third baseman in the history of black baseball. Satchel Paige considered him to be one of the two best hitters he ever faced, and Josh Gibson felt that Wilson was at least his equal as a hitter.

The lefthanded swinging Wilson was a pure hitter who had excellent power and drove fierce line drives to all fields. He earned the nickname “Boojum” because of the sound his line drives made when they smashed up against outfield fences. Wilson was a multiple batting champion, who, with a career mark of .345, posted the third highest batting average in Negro League history. He also ranks tenth in lifetime home runs, and batted .356 in 26 games against white major leaguers. In addition, Wilson recorded the highest lifetime average in the Cuban Winter Leagues, hitting .372 over the course of six seasons, including batting titles of .403 in ’25-’26 and .441 in ’27-’28 playing for Havana.

Wilson played for 10 championship teams over the course of his career, winning a title with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1929, one with the Homestead Grays in 1931, one with the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords, one with the 1934 Philadelphia Stars, and another six with the Grays between 1940 and 1945.

In all likelihood, Wilson’s mediocre fielding caused him to be elected to the Hall of Fame long after both Dandridge and Johnson. He was considered to be merely adequate at the hot corner, possessing neither the hands nor the quickness of the other two men. Wilson played third base by keeping everything in front of him, knocking the ball down with his chest, and then throwing the batter out. He was generally described as a “crude but effective workman” in the field.

Another possible reason for Wilson’s late induction may have been his reputation for being a habitual brawler. His competitive spirit and dour disposition prompted numerous altercations with opposing players, umpires, and even teammates. But Wilson’s playing ability clearly earned him a spot in Cooperstown.

Fred Lindstrom

As of 1975, only four third basemen had been elected to the Hall of Fame—Jimmy Collins, Frank Baker, Pie Traynor, and Judy Johnson. Many people began to complain that the number should be greater. In response, in 1976, the Veterans Committee elected Fred Lindstrom, who played for the New York Giants and Cincinnati Reds from 1924 to 1936. While Lindstrom was a good, solid player, it is debatable whether his selection was based more on merit or the popular opinion that the Hall was short of third basemen. Let’s take a look at his qualifications.

Lindstrom finished his career with a .311 batting average. In 1928, he hit 14 home runs, drove in 107 runs, batted .358, and had 231 hits. In 1930, Lindstrom had his finest season. That year, he hit 22 home runs, drove in 106 runs, batted .379 (a record for National League third basemen), scored 127 runs, and once again finished with 231 hits.

However, those two seasons were the only two “Hall of Fame type” seasons Lindstrom had during his career. Playing in a hitter’s era, when batting averages of .300 or better were commonplace, he never again hit higher than .319. Furthermore, his .379 average in 1930 was only the fifth best in the league.

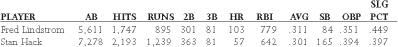

Using our Hall of Fame criteria, Lindstrom was never considered to be among the game’s elite players. A case could not be made for him being one of the ten best third basemen in history. For most of his career, Lindstrom was rated behind Pie Traynor among National League third basemen, perhaps surpassing him only in his two best seasons. He finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting only twice during his career and was a league-leader in a hitting category only once (231 hits in 1928). Perhaps even more significant is the fact that Lindstrom was a full-time player for only seven seasons. As a result, his career numbers were far from overwhelming, and were actually quite comparable to those of some other third basemen not in the Hall of Fame. One of those players was Stan Hack, the Cubs third baseman from 1932 to 1947. Let’s take a look at the numbers of the two players, side-by-side:

Lindstrom’s power numbers (i.e. home runs, runs batted in, and slugging percentage) were superior, but Hack had a decided edge in most other offensive categories. His on-base percentage was much higher than Lindstrom’s, and he scored many more runs, both critical numbers for a leadoff hitter, which Hack was. In fact, he may very well have been the best leadoff hitter in the National League during the 1930s and 1940s. In addition, he was a regular for eleven seasons (as opposed to Lindstrom’s seven), and he led the league in batting once and in hits twice. Hack also batted over .300 six times, scored more than 100 runs seven times, and was selected to the All-Star team four times. It would seem that Hack’s credentials are every bit as impressive as Lindstrom’s, if not more so. Why, then, is he not in the Hall of Fame, while Lindstrom is? Perhaps the explanation lies in the fact that Bill Terry, Lindstrom’s former teammate with the Giants, was on the Veterans Committee that elected him in 1976.

More importantly, though, was Lindstrom’s selection a good one? The evidence seems to indicate that Lindstrom was a good player who was among the best third basemen of the first half of the 20th century. Therefore, he was not a particularly bad choice. However, there were other third basemen who have yet to be elected who would have been better selections. We will soon see who some of those other players were.

George Kell

In 1983, the Veterans Committee elected George Kell to the Hall of Fame. Kell played mostly for the Detroit Tigers and Boston Red Sox from 1943 to 1957, a fairly decent era for hitters. During his career, Kell led the American League in batting once, doubles twice, and hits twice, and compiled a .306 batting average. He was also a good fielder, having led league third basemen in fielding seven times. He was selected to the All-Star Team seven times and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times.

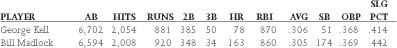

However, Kell had virtually no power. He never hit more than 12 home runs in a season, finishing his career with just 78 long balls. In addition, he knocked in and scored 100 runs only one time each during his career. Thus, it could not be said that Kell was a big run-producer, one of the more desirable qualities in a Hall of Fame third baseman. If his career numbers are compared to those of Bill Madlock, who played from 1973 to 1987, during more of a pitcher’s era, one notices a remarkable similarity:

While Kell was a far better fielder than Madlock, on offense it appears that Madlock was Kell with more power and speed. In addition, Madlock won four batting titles, twice topping the .340 mark, was a three-time All-Star, and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting twice. Therefore, Madlock’s Hall of Fame credentials are quite comparable to those of Kell. Yet he has received virtually no support.

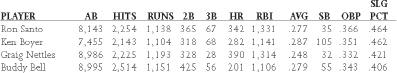

Far more disturbing, though, is the lack of support shown for both Ron Santo and Ken Boyer, two of the very best players not in the Hall of Fame. Let’s take a look at their numbers, along with those of Graig Nettles and Buddy Bell, two other third basemen with credentials just as impressive as Kell’s: