Basic Principles of Classical Ballet (3 page)

Read Basic Principles of Classical Ballet Online

Authors: Agrippina Vaganova

Vaganova’s book

Basic Principles of Classical Ballet

is now being reprinted on the basis of the third edition. The only thing omitted is a brief article of the author, “In Lieu of a Foreword”; the characteristics of the various instructional systems discussed in the article are already inadequate for the present day.

Striving to emphasize the features of the Russian school of ballet, Vaganova often compares it in her book with the French and Italian schools. These concepts cannot be applied to the current foreign ballets, although in individual cases the methods described by Vaganova still occur in choreographic practice. The simplest approach in reprinting the book would have been to omit these passages, but since the citing of examples from the French and Italian exercises helps the author to elucidate the nuances of movement, they have been retained as having a practical significance.

The fourth edition of

Basic Principles of Classical Ballet

was prepared while Vaganova was still living. A few emendations were introduced by the author; these have been taken into account in the present edition.

8

V. CHISTYAKOVA

INTRODUCTION TO THE SECOND ENGLISH EDITION

MADAME VAGANOVA has written a work that should be found on every dancer’s bookshelf. As a distinguished professor and custodian of a great tradition, she has produced a comprehensive and unaffected text book of real value. Her outlook is so refreshingly broadminded and professional; there is a real sense of proportion towards that vexed question—traditional schools and their technical differences. What a lesson there is in her balanced judgement, her unbiased approach. A life of study and devotion to the ballet has given her a rich store of knowledge, and a real insight into her pupils’ requirements, and with the wisdom of those who know, she shows that there is no way of unduly hurrying the leisurely development of the perfect dancer.

That one might argue a point or two within these pages is of no real significance or importance. The brow that covers the mind behind this work is broad enough to demand our universal tolerance and blessing; and the mind behind that brow has acquired the only form of freedom of outlook that matters; that which springs naturally from an assimilated knowledge that is the result of a great discipline.

In this short foreword I salute the Russian School of Ballet, and pay a little of the homage that is due to a great professor.

NINETTE DE VALOIS

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

9

A FEW EXPLANATORY remarks about the method of description used in this book.

First of all about the French terms accepted for the various conceptions of classical ballet. As I have long since indicated in discussions on this subject, the French terminology is unavoidable because of its international character and universal acceptance. It is similar to the use of Latin in medicine and English in sports.

In describing the forms of classical ballet I used an order which, in my opinion, is convenient for those who wish to acquaint themselves with classical ballet as a whole. For this reason I grouped the descriptions of battements, jumps, turns, etc., in an order which does not follow the order of their teaching, but which offers a simple systematization of the entire material in this book. In each chapter the description of steps is carried from the simplest form to the most complex and difficult, so that even the non-professional reader may be able to find easily the information in which he is interested.

Those who wish to acquaint themselves with the order of exercises given during a lesson, with the combinations of steps, etc., will find this information in the chapter on the construction of a lesson and in the examples furnished with the various descriptions.

In the descriptions of the various steps, I say that the right foot is front, or that the right foot begins a movement without modifying the description each time by saying that the movement may also be begun by the left foot, or that the left foot may be in front. I do this for the sake of conciseness of description, for convenience. The left foot may and should be used as often as the right one.

I also try not to repeat the description of a once-described method of execution, if that method was included in the description of another step. The reader, coming across an unknown term, must look up this term in the index and read its description in the indicated place.

In the majority of cases I give the description of a step in its full form, in the centre of the floor, with arms; if in the illustra-tion that accompanies the description the step is shown at the barre, the arm movements can be easily added from the description in the text.

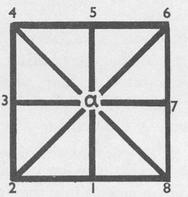

To indicate the degree of the turn of the body, or the specific direction of a movement, I use the diagram reproduced here. On it: a—indicates the position of the pupil on the floor, I—the middle of the footlight line, 2—the corner in front and to the right of the pupil, 3—the middle of the right side, etc.

1. Floor plan. The spectator is at point 1; the dancer at point a

Our school accepts the method of measuring the position of the arms and legs used in anatomy. We indicate in degrees the angles formed by the arms and legs in relation to the vertical axis of the body. But it must be understood that we speak in general terms when we say that a leg is raised to 45 °, 90°, 135°, because the angle formed by the leg and the body depends on the individual structure of the dancer. In other words, a 90° angle does not always equal a mathematical 90°; it is a conventional description of the horizontal position of the leg with the toe on the level of the hip.

I could not decide whether to use the precise anatomical and bio-mechanical terminology in defining the parts of the body, legs and arms. In the end I gave up this thought because I knew that these scientific definitions are much too seldom used among dancers. Although it may be clumsy writing, I prefer to say each time: “the upper part of the leg from the hip to the knee”, “the lower part of the leg, from the knee to the toe”, etc. It may not be very literary, but I thus avoid the possibility of a misunderstanding.

10

Table of Contents

DOVER BOOKS ON CINEMA AND THE STAGE

Title Page

Copyright Page

INTRODUCTION TO THE FOURTH RUSSIAN EDITION

INTRODUCTION TO THE SECOND ENGLISH EDITION

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

INTRODUCTORY - CONSTRUCTION OF LESSON

I - BASIC CONCEPTIONS OF CLASSICAL BALLET

II - BATTEMENTS

III - ROTARY MOVEMENTS OF THE LEGS

IV - THE ARMS

V - POSES OF THE BODY

VI - CONNECTING & AUXILIARY MOVEMENTS

VII - JUMPS

VIII - BEATS

IX - POINT WORK

X - TURNS

XI - OTHER KINDS OF TURNS

SAMPLE LESSON

SAMPLE LESSON WITH MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT - For senior and professional classes

SUPPLEMENT

INDEX

A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS - IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

INTRODUCTORY

CONSTRUCTION OF LESSON

THE STUDY of any pas in classical ballet is approached gradually from its rough, schematic form to the expressive dance. The same gradation exists also in the mastering of the whole art of the dance, from its first steps to the finished dance on the stage.

The lesson does not unfold immediately as a whole but develops through exercises at the barre and in the centre to adagio and allegro. Children who begin to study at the start do exercises at the barre and in the centre only in dry form, without any variations.

Then simple combinations at the barre are brought in and repeated in the centre. Basic poses are studied. Further, easy adagio is added, without complicated combinations, so that it serves only to acquire stability.

Complexity is brought in by combinations of movements, into which we introduce work with the arms. In this manner we gradually come to the combined, complicated adagio. All movements which I describe below in their most elementary form are done on half-toe.

Finally, jumps are brought into the combinations of adagio, which lead the pupil to ultimate perfection.

In adagio the pupil masters the basic poses, turns of the body and the head.

Adagio begins with the easiest movements. With time, it gets more and more complicated and varied. In the last grades, difficulties are introduced one after another. Pupils must be well prepared in the preceding grades to perform these complicated combinations—they must master the firmness of the body and its stability—so that when they meet still greater difficulties they do not lose their self-control.

A complicated adagio develops agility and mobility of the body. When, later in allegro, we face big jumps, we will not have to waste time on mastery of the body.

I want to dwell on allegro and stress its particular importance. Allegro is the foundation of the science of the dance, its intricacy and the bond of future perfection. The dance as a whole is built on allegro.

I do not consider adagio sufficiently revealing. The dancer is assisted here by the support of her partner, by the dramatic or lyric situation, etc. It is true that a number of difficulties, even virtuosities, are now introduced into adagio, but they depend to a great extent on the skill of the partner. But to come out on the stage and make an impression in a variation is something else: here is where the subtleties and finish of your dance will be shown.

And not only variations, but the majority of dances, both solo and group, are built on allegro; all valses, all codas are allegro. It is vital.

And if we look back, we see that until now everything was just a preparation for the dance. Only when we reach allegro do we beging to study the dance. And this is where the whole wisdom of classical dancing is revealed.

In a burst of joy children dance and jump, but their dances and jumps are only instinctive manifestations of joy. In order to elevate these manifestations to the heights of an art, of a style, we must give it a definite form, and this process begins with the study of allegro.

When the legs of the pupil are correctly placed, when they have acquired a turn-out, when the ball of the foot has been developed and strengthened, when the foot has gained elasticity and the muscles have toughened—then may we approach the study of allegro.

We begin with jumps which are done by a rebound of both feet off the floor, changement de pieds and échappé. To make them easier they are done in the beginning at the barre, facing it and holding on with both hands.

The next jump to be done is assemblé, rather complicated in structure. This sequence has deep and important reasons.

Assemble forces the dancer to employ all muscles from the very start. It is not easy for the beginner to master it. Every moment of the movement has to be controlled in performing this pas. This eliminates every possibility of muscular looseness.

The pupil who learns to do assemblé properly not only masters this step but also acquires a foundation for the performance of other allegro steps. They will appear much easier to the pupil, but in spite of it she will not be tempted to do them loosely. The correct setting of the body, the full control of it, once mastered from the first pas, becomes a habit.

It would be infinitely easier to begin to teach balancé, for example. But how can we instill in the pupil the correct manner of holding the body, or controlling the muscles? Because of the easiness of this step, the legs loosen involuntarily, and the pupil does not learn to turn-out as in assemblé. The difficulties found in assemble lead directly to our goal.

After assemble we may pass over to glissade, jeté, pas de basque, balance. The latter, I repeat, should not be introduced until the muscles are fully developed in the basic jumps, and the jump is given its proper foundation.

Having learned how to do jeté we pass over to jumps on one foot, with the other foot remaining sur le cou-de-pied after the jump, and to sissonne ouverte to various sides. At the same time we may study pas de bourrée for, although this step is done without leaving the floor, it requires very steadily placed feet. At this period of development of the pupil we may begin to give her simple dances.

In the highest grades we study the most difficult sustained jumps and leaps, for example saut de basque. The most difficult of them, the cabriole, completes the study of allegro.

I dwell longer on allegro because it is the foundation on which the dance as a whole is based.

In the higher grades, when it becomes necessary to make the lessons more and more complicated, all steps may be done en tournant. Beginning with simple battement tendu and ending with the most intricate adagio and allegro steps, everything is done en tournant, affording the developed and strong muscles harder work.

I cannot give a rigid plan for the construction of lessons. This is the realm where the decisive part is played by the experience and sensibility of the teacher. It requires absolute individualization.