Basil Street Blues (10 page)

Read Basil Street Blues Online

Authors: Michael Holroyd

Perhaps the separation between husband and wife had been too long postponed. In any event it seems to have been peculiarly bitter, and whereas the unpleasantness of it all paralysed Fraser, it released a hailstorm of recrimination from Adeline. Her husband is now a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The children cannot credit this. Certainly they do not want to, but they do not know what to believe. The worst that can be said of him, they think, is that he is weak. For years they have seen how weak he has been with their mother. Is he now being weak with another woman?

Yolande’s pressing letters to her father are obviously not unsympathetic but they express her bewilderment. What were the facts? Surely it must be possible to put everything right by a family discussion about it all? Fraser’s last note is his reply to this suggestion.

Discussions more especially on subjects where I am unable to make concessions are distressing, & when I know that your minds have been poisoned by misrepresentation & the withholding of important facts.

I am grieved that you have felt the strain of the position – your letters were greatly appreciated – but because I am not for the

moment

able to confide in you please trust me & do not believe all you hear. Time will I am sure show that your belief in me is not misplaced & this will I hope repay you for the sorrow you have suffered.

I have been wronged for years and it was only my love for you three children which enabled me to endure so long.

You are & will always be in my thoughts – I have no wish to ostracise…

And there the letter stops. There is no mention of the woman in the case. Perhaps, by staying at the Royal Automobile Club, Fraser was concealing her presence in his life for as long as possible. But by the early summer of 1927, after he bought her the flat in Piccadilly and made his legal Settlement with Adeline and his family, the truth must have been known to them all. It was the old story. Adeline was aged fifty and Agnes May thirty. Adeline had given birth to four children; Agnes May apparently had no children. She was a glaringly attractive woman – an expensive tart, my father irritably thought when he eventually met her, whom Fraser insisted on treating as a great lady. But she was also sympathetic and understanding, sexy and loving to Fraser who believed that Adeline’s loveless complaints over the years had worn away all good feeling and were the real cause of their failed marriage. At any rate, he could stand no more. He had that special sensitivity to women that some men whose mothers die early retain all their lives. The fact that his mother had killed herself may have acted on him as an inhibition – though I do not know whether he was ever told that she had killed herself. In any event, his need had grown so acute through neglect that he was driven to actions which people who thought they knew him found incredible.

But what had attracted Agnes May to Fraser? He was in his early fifties, six feet tall but rather bent, with ears that stuck out as if straining to understand what was going on, and bald though his face was decorated with what, after the rise of Hitler, was to be known as a Hitler moustache. He was a generous but not a glamorous man, a gentleman in the Edwardian style who, though desperately wanting to be young, could not shimmy or foxtrot or even ‘Tip-toe through the Tulips’. He would have liked to belong to the new generation with its jazz and tangoes, its naughty sentimental songs, but he could not really join in. His moment of youth had been too long delayed; and what Agnes May gave him, however vital and necessary, was probably as much part of his imaginative as his physical life. He did not care much for nightclubs and cabarets,

thés dansants

and musicals. Also he felt guilty at being unable to ‘do the right thing’ and offer Agnes May marriage, and did not object when she called herself Mrs Holroyd.

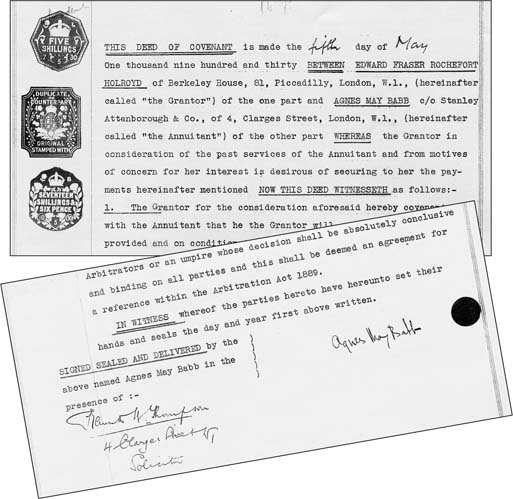

The affaire lasted four years altogether, during three of which Agnes May lived in Piccadilly as Fraser’s mistress. Then he had grown tired and she had become bored. The arrangements for their separation were spelt out in an extraordinary Deed of Covenant dated 5 May 1930 and drawn up by a solicitor in Clarges Street, round the corner from Berkeley House, rep resenting Agnes May. In consideration of ‘past services’ and from ‘motives of concern for her interest’, Fraser states that he is ‘desirous of securing to her’ the payment of £33 6s 8d each month – or in other words £400 a year (equivalent to £13,000 seventy years later). The first payment has already been made on 1 April, and these monthly payments were to continue for ten years or during the joint lives of them both ‘whichever of two such periods shall be the larger’.

But there are conditions attached to these payments. Agnes May must lead a chaste life. If she ‘returns to cohabitation with her husband’ Thomas Babb, or divorces him and remarries, then the monthly allowance will be forfeited. And there are other things she must not do: she must not call herself Mrs Holroyd any longer; she must not ‘come to reside within two miles’ of Fraser’s family house at Maidenhead or ‘hold any communication’ with his family; she must not lay claim to ‘his Lancia car’ or become a bankrupt (though there seems more likelihood of him entering bankruptcy than her). If these conditions are met, the allowance will continue to be paid to her on the first of each month, and she agrees to inform Fraser through his solicitor of ‘her exact place of residence’ every three months – providing that he does not disclose this address to his family as she does not want to be molested by them.

This strange document has lain for many years with a small bundle of my father’s out-of-date Wills, divorce and tenancy papers, long ago forgotten. ‘She faded out of the picture with a minimum of fuss,’ he wrote of Agnes May in his brief account. ‘I suppose she was given some money but I’ve no idea how much. At the end of it all we were very broke.’

The Deed of Covenant is signed by Agnes May Babb in a spiky, slightly backward-leaning hand. I touch it with my finger. It is this signature alone that has given me her name and provided a small crack in the dark, enabling me to find out more about her.

By trawling backwards over the years at the Public Search Room at St Catherine’s House I came across Agnes May’s previous marriages and her birth certificate. Now I travel forwards to find out whether, after she had separated from my grandfather, she remarried. From my grandfather’s point of view the good news (since it put an end to his monthly payments) is that she did marry again on 15 February 1934. Her husband was a thirty-year-old divorcé and ‘company director’, Reginald Alexander Beaumont-Thomas.

Agnes May Beaumont-Thomas (formerly Babb, previously Lisle and initially Bickerstaff, who for two or three years adopted the name Holroyd) calculates her age on the new marriage certificate as thirty-six (which is only two years short of her actual age) and she describes her father as a hotel proprietor which she remembered having copied down on her certificate of marriage to Thomas Babb. Her father appears to have had a biblical ability to die and come alive again fairly regularly. At the time of her first marriage, she writes that he is ‘deceased’ as her husband William Lisle’s father was; but he was alive four-and-a-half years later when she married Thomas Babb (whose own father was alive), and had died again by 1934 now she was marrying Reginald Alexander Beaumont-Thomas (whose father was also dead). Actually he did not die until 1942. He died intestate, so there is no mention of a daughter. Despite her wealth, his estate, which went to his widow, was valued at only £207 3s 6d.

The Beaumont-Thomases are married at Biggleswade in Bedford and Agnes May gives her address as ‘The Red Lion Hotel, Sandy’. But to have remarried, she would have had to get divorced. The decree nisi had been granted on 13 June 1933, and the bad news for my grandfather is that he has been named as co-respondent – though it is more than three years since he has been living with her. Perhaps this is no more than a legal convenience since his name is written with no great accuracy on the divorce proceedings – Edwin (instead of Edward) Fraser Rochford (instead of Rochfort) Holroyd. It seems unlikely that damages would have been sought against him but he may well have had to pay the court costs. What is surprising is that even an inaccurately-named co-respondent has been necessary, since husband and wife were living apart for more than eight years (had she gone back to him, her adultery with my grandfather would have been condoned). The speed with which she marries again is spectacular – even quicker (three days versus eleven days) than her first remarriage. For this was a very good marriage she was making. Her late father-in-law, Richard Beaumont Thomas (the name was not then hyphenated), a steel and tinplate manufacturer of Brynycaerau Castle, Llanelly, Carmarthen, had left £419,285 18s 9d to his three children on his death in 1917. Such a sum would be worth £14 million at the end of the century.

For two years Agnes May Beaumont-Thomas continued living with her company director husband in Campden Hill Gate. Then they leave London – perhaps to one of the properties he had been given in Gloucestershire, perhaps abroad (his first wife had been French and they had married in Paris). I can find no further trace of them. So Agnes May disappears from my story, like an alarming comet passing over the night sky.

*

But was there nothing more I could discover about the ramifications of this affaire? Suddenly I recalled the mysterious ‘Holroyd Settlement’ my father had mentioned in the account he wrote for me of his early years, and which still provided him in his old age with a couple of hundred pounds or so a year from the National Westminster Bank. This Settlement had occasionally been spoken of in hushed and hopeless whispers during my early years. I remember my mother telling me how she and my father took me, aged six or so, to the home of a famous lawyer, Sir Andrew Clark, who had been a friend of my Uncle Kenneth’s at university. He was reputed to be the cleverest barrister in England and was much disliked for his arrogance (he later gained fame for a brilliant investigation into the Ministry of Agriculture known as the Crichel Down Inquiry, and also for cutting off his daughter with exactly one shilling when she married an unacceptable man). My mother was terrified that I would smash one of the precariously-placed objects in his drawing-room as I wandered happily from table to table and my father appealed to him to release us from the iron grasp of our family Trust. I broke no china that afternoon, nor was the Trust Deed broken. My grandparents, my uncle, my aunt, everyone wanted it broken: and yet it could not be broken. The letter of the law was too strong. Somewhere in its legal depths, like treasure in a long-sunken wreck, lay the money we so desperately needed. It remained as if in a chest whose key is lost, its contents slowly disintegrating.

But what the origins of this complex affair were I never knew. At my request the National Westminster Bank now sent me the documents from its vaults and I could see what I had begun to suspect: that the ‘Holroyd Settlement’ was the legal arrangement made by my grandfather in 1927 after he left his family, together with a Supplemental Deed dated 27 May 1932 which reveals something of what happened over those five years. It is a ruinous story.

Two properties are identified in this Supplemental Deed. The first is Agnes May’s expensive love nest in Piccadilly, the lease of which did not expire until June 1946. The second is an oddly-crenellated, nineteenth-century town cottage with a small garden. It resembles a gate house to some grander building. Auckland Cottage, 91 Drayton Gardens, in unfashionable Fulham, is where my grandfather retired in April 1930. The rent on this house was £200 a year (equivalent to £6,000 in the late nineteen-nineties) and the lease did not expire until March 1944. These two properties Fraser handed over to Magor and Anderson, his trustees, in place of his Maidenhead house. They were to sell or sub-let them once he returned to Maidenhead so that his payments to his wife and children, promised in the principal deed, could be kept up. All his Rajmai Tea shares were now in other hands. A small design shows the details of these loans and overdrafts he had so far secured.

| Amount owing | Name of Bank | No. of shares |

| £24,500 | Mercantile Bank of India Ltd. | 1,000 Transferred to the name of the Nominees of the Bank. 100 Collateral. |

| £8,000 | National Bank of India Ltd. | 227 Transferred to the name of the Nominees of the Bank. Guaranteed by Messrs. Geo. Williamson & Co. |

| £10,000 | Major Holroyd | 300 In Major Holroyd?s name. |

| (He owes Lloyd?s Bank for this amount.) | ||

| £5,000 | Barclays Bank Ltd. | 125 The amount of £5,000 is being repaid at the commencement of June. |

| Total number of shares | 1,752 |

All the family were required to sign this new Deed, Basil getting as his witness the British Consul in Venice where he happened to find himself in the early summer of 1932.

But he was back in England that July and accompanied Fraser to a nursing home near Blandford in Wiltshire where his Uncle Pat had gone following an operation. My father hardly knew his uncle, beyond recognising him as a handsome, mild-mannered man with a liking for drink. In the account he wrote for me almost fifty years later, he recalled ‘finding my Uncle Pat tiptoeing down the stairs at Brocket when he was staying a few days with us. It was one o’clock in the morning and he was on his way to the dining-room for one more whisky.’ According to my father it was whisky that killed him at the age of fifty-eight. He was suffering from a duodenal ulcer, an infected appendix, a blockage of the intestinal canal and chronic constipation. That was how Fraser found him at the nursing home. As with their father, and with his son who died in infancy, Fraser is again ‘present at the death’ on 15 July 1932. Even Basil’s regular high spirits temporarily drooped, those high spirits on which he depended to overcome his sense of being unwanted, ‘an evident mishap’. He never forgot that awful white room in the nursing home and ‘my father’s great distress at his brother’s death’.