Basketball Sparkplug (3 page)

Read Basketball Sparkplug Online

Authors: Matt Christopher

In the fourth quarter Allan Vargo caught a long pass from Ron and laid it up for a perfect shot. Dutchie came back in and

replaced Kim. He was full of pep. He scored four points in less than two minutes and the crowd went wild.

The Bucs scored again, but the Arrows kept going strong. When the final

whistle shrilled, the Arrows were ahead, 34 to 32.

On Saturday they beat the Crackerjacks, 52 to 31. But the Crackerjacks were the cellar team, and beating them wasn’t anything

to brag about.

Kim still missed most of the practices. Coach Stickles asked him once why he didn’t come to all of them.

“I have to stay home and practice singing,” Kim told him. “And twice a week our choir meets in the church for practice.”

It seemed to Kim that Coach Stickles couldn’t understand why a boy who liked to play basketball would also like to sing.

“Okay,” the coach said. “But it’s too

bad. You’ve got the makings of a good basketball player.”

Kim knew he would never forget what the coach had said.

In the game against the Rockets, Kim went in when the Rockets were ahead, 8 to 4. It was the first quarter. Kim thought the

coach wanted him to stop that tall, dark-haired Rocket from running the score up any higher. He had scored six of the eight

points. He looked very good.

The Arrows had the ball. Allan passed it to Ron, who ran down the right side line, stopped, and faked a shot for the basket.

A Rocket player jumped in front of him and Rod threw to Kim. Kim pivoted as his man tried to hit the ball

from his hands. He kept his back to the boy, and no matter how the Rocket player tried he could not get near the ball.

Kim saw Jimmie break for the basket. Kim leaped off the floor and flung a one-hand pass to him. Jimmie caught it, bounced

the ball once, then jumped. A perfect layup!

Jimmie smiled as he and Kim ran upcourt. They winked at each other.

Kim ran to cover his man, who was taller than Kim. He seemed to be all legs and arms, but he moved fast. Kim had a tough time

keeping between him and the ball.

All at once a long pass sailed upcourt toward the Rockets’ basket. Kim

whirled, and caught his breath. His man had gotten away from him! The tall Rocket player was running to catch the ball, his

long white legs pumping up speed.

Kim rushed after him, but the ball sank into the Rocket’s hands just before Kim got there. The player spun, started to lift

the ball above his head to shoot, then stumbled. He fell against Kim, who reached out his hands to stop him from falling.

The whistle shrilled, Kim whirled. Up the court came the referee holding up two fingers!

Kim stared. “What did I do?”

“Tripping!” said the referee.

“Tripping?” Kim’s mouth fell open.

“But I didn’t—” He paused. He wouldn’t argue with the referee.

“Hey! What’s the big idea?” one of the spectators shouted. “The kid tripped himself!”

“Get the ref out of there!” another yelled. “He’s blind!”

Kim stepped into his spot behind the white line and waited for the Rocket player to try his two free throws.

The first sank without touching the rim. The second hit the backboard first, then bounded through.

It wasn’t my fault, Kim told himself. I hope Coach Stickles knows that.

T

HE coach took Kim and Jimmie out in the second quarter. He didn’t say anything to Kim about the personal foul the referee

had called on him. It bothered Kim. Maybe the coach thought he had tripped that boy.

Anyway, those two points were the only ones the Rocket player had scored on Kim, But the Rockets were still ahead, 12 to 8.

The Arrows could not seem to get going.

A personal foul was called on Ron when he tried to stop a player from making

a drive-in shot. The Rocket player made the first free throw. He missed the second. Ron caught the ball and dribbled down-court

to the halfway line. He passed to Jordan, who tried a set shot. The ball banked off the board. Bobbie Leonard caught it. He

shot, but missed. A Rocket player got the ball and heaved it upcourt.

Kim saw the coach shake his head and strike his fist against his knee. “We’re just not lucky today!” he said.

The half ended.

ROCKETS

—17,

ARROWS

—8.

During the ten-minute intermission Coach Stickles told his boys to stay close to their men when they were on the defensive;

not to get rough; to get long

shots only when they had to. Pass, pass, pass. Work the ball close to the basket, then shoot.

“Never argue with the referee,” he added, “even when he is wrong, as he was when he called that personal on Kim. Sometimes

he doesn’t see the play from a proper angle, but he has to call it as he sees it.”

The words stuck with Kim. No matter if they did lose some of their games, Coach Stickles was a good, smart coach.

Jimmie Burdette started in the second half. He made two baskets, both long shots, but the tall Rocket player with the long

arms and legs was dumping them in like marbles into a tomato can.

“It looks as if nobody can stop him

but you, Kim!” the coach said. “Get in there!”

Kim got in there. He didn’t stop the tall boy altogether from making baskets. The boy sank two for four points. But that was

all. And Kim had scored three points. All in all, it wasn’t bad for eight minutes of play—two in the third quarter, six in

the last.

The Arrows finished on the short end, 36 to 28.

T

HE line-up was in the paper the next day. Kim clipped it out as another treasure for his scrapbook.

One sentence was in fine print about a Rocket player who had scored the most points. Another sentence told about Allan and

Jimmie both scoring eight points for the Arrows. Kim read every word, hoping there might be something written about him. But

there wasn’t.

He looked at the clipping again.

| | fg | ft | tp |

| Tikula f | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Burdette f | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Vargo c | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Leonard g | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| O’Connor g | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Jordan f | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| | 10 | 8 | 28 |

Well, at least he was playing as much as the others, even though he didn’t practice as often.

If he could only practice more he’d make more baskets. Maybe Coach Stickles would put him in as forward.

But he—he had to attend choir practice, and practice singing at home. That was what took his time. Suppose he did not sing.

He could attend all the basketball practices then. He could develop a

good eye for shots. You don’t have to be tall to be a good shot. Jimmie Burdette wasn’t tall, was he?

Kim’s mother came into the room. She had on a dark blue dress with a black patent-leather belt around the waist, and the new

blue shoes Daddy had bought her for Christmas.

Kim thought of how much she loved to hear him sing. He remembered how she looked when she sat at the piano playing for him.

She looked as happy as on her birthday when Daddy gave her a gift. Kim knew that no matter what happened, he would never give

up singing.

His mother asked, “Don’t you think you’d better get dressed?”

His eyes widened. “Where are we going?”

She smiled. “It’s a surprise,” she said. “Get dressed. We’ll tell you later.”

He didn’t like to be teased. It made him excited.

“Oh, Mom!” he cried. “Please tell me!”

Then his dad came in. He had on a white shirt and a flashy yellow necktie. He was holding three tickets in his hand.

Kim’s heart jumped. Now he knew!

“We’re going to the Lions-Philadelphia game!” he cried.

“Right!” laughed his father.

K

IM watched the big gymnasium fill up with people. Music blared from loud-speakers. Boys sold programs. Kim’s dad bought one

for him.

“I’ll keep score!” Kim said breathlessly. “Got a pencil, Dad?”

His father gave him a pencil.

The Philadelphia Ravens trotted out onto the floor. They were dressed in yellow jackets and long yellow pants. They had four

basketballs which they began to throw at the basket. Kim watched excitedly.

There must be a dozen men on that team!

After a while the Seacord Lions trotted in. They were in bright green. Everybody cheered and whistled.

“There’s Thompson!” cried Kim. He knew most of the players from watching them on television. “And there’s Wally Goodrich!

See him, Dad? See him? Boy! Just watch him!”

The players on both teams began to remove their jackets. That made them look even taller than before. Thompson must be about

six feet six. Reynolds, six feet seven. Kim was sure Wally Goodrich was six feet four. He knew more about Wally than he did

about any of the others.

Kim opened the program and found the players’ names. Wally Goodrich, 24 years old, six feet four inches. He was right. He

read through the others. Wow! Such giants! Philadelphia had a man six feet nine! A player like that had only to hold the ball

over the basket and drop it in!

Two referees appeared. They wore black pants and black and white striped shirts. The music stopped playing. An announcer spoke.

He gave the names of the starting players of both teams. Then the national anthem was played and everybody stood up. When

it was over, the people sat down.

The game began.

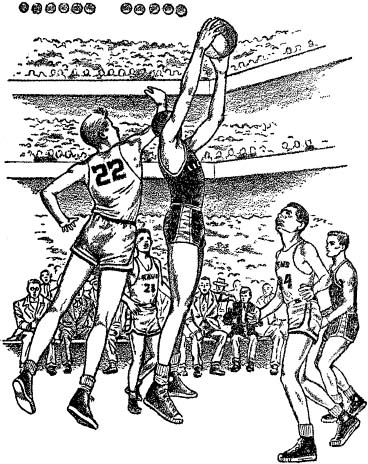

All the players wore jerseys and shorts

now. A referee tossed the ball up between the two giant centers. Long fingers tapped it. Philadelphia got it, passed it to

another Philadelphian. A Lion player snared it!

Kim jumped to his feet. “Wally Goodrich caught it, Daddy! That was Wally—”

His heart thumped like a hammer against his ribs. He sat on the edge of his chair, one hand gripping the program, the other

the chair in front of him. Wally dribbled the ball down-court, running as if he were carrying the ball. All at once he passed.

The next second the ball was passed back to him. He leaped for a hook shot. Made it!

“See, Dad?” cried Kim. “He’s good!”

The ball was passed upcourt. Kim had trouble keeping track of it. These players moved with the speed of lightning. A basket

was made almost every five seconds. First the Ravens made one or two. Then the Lions did. It was too fast for Kim to put down

on paper. He stuck the pencil into his pocket. He could not watch the game and keep score too.

When the half ended, the score was

SEACORD LIONS

—48,

PHILADELPHIA RAVENS

—47.

During the intermission a Philadelphia player was named the outstanding player of the month, and given a wrist watch.

“Wally Goodrich was outstanding player last month,” Kim said.

The second half was as lively and exciting as the first. Substitutes came in often. Wally Goodrich went out and then came

back in two or three times. Kim enjoyed the way he faked when a guard came up to him. Twice he bounced the ball behind him

with his right hand and continued bouncing it, without interruption, with his left. Another time he faked an overhand pass.

When the guard jumped, Wally dribbled under his arm and laid one up for an easy two points. It looked easy, anyway.

Kim noticed that Wally shot his fouls with one hand. He would raise the ball to his right shoulder with both hands,

then push the ball up with his right hand. He made it almost every time.

Just before the game was over, Kim asked his father for a favor. His father smiled and nodded.

The score was still close when the game ended. The Seacord Lions won, 101 to 98.

When they went home, Kim had a name scribbled in pencil on the back of his program.

It was

Wally Goodrich

.

O

N the following nights, as he practiced singing at home and with the choir, Kim thought about the team practicing basketball

in the gym. Some of those players, like Allan and Jimmie, might one day play for the Lions. They practiced all the time. Sometimes

he could not understand how they got such good marks in school. But they studied too, of course.