Behind Mt. Baldy (33 page)

Traffic was racing past at high

speed and with irritating frequency.

Roger didn’t like that. He

wrinkled his nose at the engine fumes and said, “Let’s keep going and find somewhere

nicer for lunch.”

The others agreed and stood up.

As they adjusted their gear Peter asked, “Which way?”

Graham pointed.

“Down to that bridge to the right.

That is the Barron River.

Just across that is a road going off on the left. We take that,” he replied.

It was 500 metres to the bridge

but in the five minutes it took them to walk the distance at least ten vehicles

roared past, buffeting them with wind, fumes and dust. The Barron River at this

point was barely ten paces wide and the banks were all choked with bushes,

lantana and weeds.

The boys had to wait for a truck

to pass before crossing the short bridge, then again for two cars before

crossing the highway and starting along the bitumen road heading west.

“Thank God for that! It’s a

relief to get away from all that traffic,” Roger said. The side road curved

left, then right. To their left was open pasture, on the right open timber, the

trees all magnificent white gums with wonderfully straight trunks. The road

also became straight. The bitumen gave way to gravel. Roger eyed it with

disfavour and lowered his head to look at his feet as he plodded along. A truck

rattled past from the other direction, grey dust billowing in its wake. This

set the boys sneezing and cursing.

“Ah

yuk

!”

Stephen snorted. “Are we going to stop soon?” He took off his glasses and wiped

off a film of dust.

Graham looked at his watch.

“Quarter to twelve. OK. We stop at the first shady spot we come to.”

Roger had a drink to wash grit

off his teeth. “I need to refill my water bottles soon,” he said. He started to

feel very thirsty and was aware his headache was coming back. It became an

effort to keep going now that the idea of stopping was fixed in his mind. He

drained the water bottle. Sweat stung his eyes. His boots felt heavier, his

feet very sore.

They boys passed another stand of

white gums. There were a few houses scattered in the open bush, just visible

over the high blady grass lining the verge. With each step they got closer to

the mountains until, at a bend with a road junction they reached the gentle

change of slope at their base. Here the road swung to North West and skirted

through open bush along the base of the mountain, the ugly scar of a gravel pit

on their left.

Just after they had rounded the

bend a car

came

racing up behind them. It took the

corner at high speed. Roger heard it and glanced back, yelled a warning to the

others; and stood transfixed. The car raced past, its tyres thrumming on the

corrugations.

It was a grey Mercedes!

With four men in it!

They wore white shirts and ties.

‘The driver was- don’t waste time looking at the driver! Look in the back. Too

late!

A thin man with grey hair and a moustache?’

“A grey Mercedes!” he cried,

watching it vanish around the bend ahead of them.

“The White

Falcon!

We must tell Inspector Sharpe!”

“Did you get the number of the

car?” Stephen cried.

Roger felt a flush of shame. “No.

I didn’t think of it. I was too surprised,” he replied in a crestfallen voice.

“It is heading towards Atherton,”

Graham added.

Roger began to walk as fast as he

could. “Quick! Let’s find a house with a telephone,” he said. He was so keen to

do this that he was oblivious to his aches and panting breath.

“Slow down Roger. You’ll keel

over from the heat. You’re all red in the face,” Graham said as he strode up

beside him.

Roger realized his heart was

beating very fast and that black dots were dancing before his eyes. He slowed

his pace and suddenly felt dizzy. He felt Graham grab his arm to steady him.

“Stop Roger!

Stop!”

Graham ordered.

Roger did as he was told, weakly

protesting. “But the White Falcon will get away!”

Stephen snorted.

“White Falcon!

Probably just the local Real Estate Agent

showing some prospective buyers a farm,” he commented.

Roger bit his lip. He felt silly and

ashamed of his weakness. He unscrewed the top of another water bottle and

drained it.

Graham nodded with approval.

“Drink some more. You look very flushed,” he ordered.

“Out of water,” Roger croaked.

Peter passed him a water bottle.

Roger had a mouthful and passed it back. “I’m OK now. I was just excited. Come

on. Let’s find a phone before they get away.”

“Relax. They will already be in

Atherton mate. By the time we find a phone they will be miles away. We will

just go on, nice and steady,” Graham replied.

They resumed their walk and in

five minutes a house came into view, a modern brick bungalow of the ‘5 Acre

block’ type. The boys went in and knocked. A grey haired lady cautiously

answered the door. When Graham removed his hat and politely asked if he could

phone the police she assented. He dropped his pack and webbing.

“You blokes stay here. I will do

the phoning.”

Roger met the lady’s gaze. “May

we fill our water bottles please?” he asked. He really wanted to be the one to

phone but accepted that Graham was the senior; and the lady wouldn’t want them

all trampling through her home in their sweaty uniforms.

While the lady led Graham inside

the others went to a tap to fill all the water bottles. Roger filled Graham’s

as well. He drank until he felt bloated, then refilled his own.

In five minutes Graham was back.

“The Inspector wasn’t there but they promised to pass on the message,” he

explained.

Roger felt a sharp disappointment

which he knew was unreasonable. But he felt better knowing the message had been

passed and after a drink and rest. He was perspiring freely again and realized

he must have been getting heat exhaustion. Heat exhaustion! In mid-winter on

the Tablelands! He looked up. Still not a cloud to be seen except for the few

blobs of cotton wool on the mountain tops to the west.

The boys thanked the lady and

walked back out onto the road.

“What about lunch?” Stephen

asked.

It was 12:40 Roger noted. Only a

hundred metres further on two dirt roads turned off on the left amongst a stand

of trees; one up the slope and the other through a gate to a house. At the

junction was a grassy area well shaded by the

eucalypts.

“This will do us,” Graham said.

“It’s not as private as I’d like though.”

“It’ll do. I’m starving,” Stephen

replied. He dropped his pack and the others did likewise. Roger sat on his pack

and rummaged in his webbing for food but he did not feel hungry. He decided on

a tin of peaches, some biscuits with apricot jam, and a cup of coffee.

“Boots off.

Air your feet,” Graham ordered.

Peter groaned. “But I will have

to move then,” he complained in an aggrieved tone.

“Why?”

“Because of the

stench from your gungy feet!”

“Bite your bum!”

They all laughed. Roger took off

his boots and socks and stretched his toes. It felt better at once. He examined

his feet and renewed one piece of sticking plaster but was pleased to note

there were no new blisters. Using a spoon he ate the peaches from the tin.

Already he felt much happier.

While sipping his coffee Roger

pulled out his maps and began to calculate how far they had walked.

Graham swallowed some food and

called, “How far do you make it Roger?”

“Eighteen kilometres,” Roger

replied. He felt proud of the achievement.

“That’s about what I reckon,”

Graham agreed.

“Nearly time to find a camp site then,”

Roger said.

“Another seven.

Let’s make it twenty five.”

Roger grimaced. “Till I can’t go

any more,” he temporized.

Peter sat up. “How far is it to

that tunnel?”

“Only six in a straight line,”

Graham replied.

Stephen leaned over to look at the

map. “Which way are we going? Up the railway or along the road?” he asked.

“The road is further,” Peter

said.

“By a lot.

Be all that awful traffic too,”

Roger replied.

“I vote we go up the railway,”

Graham said.

“Let’s wait and see what it is

like,” Stephen cautioned.

At 1:30pm they resumed their

march. Only a hundred metres further on the road crossed a small creek which

was flowing. It was only ankle deep but was crystal clear on a sandy bottom.

“Oh! I wish we’d known this creek

was here,” Peter said.

“Let’s stop and have a wash,”

Roger suggested.

Graham shook his head. “No. We’ve

only just started again and we’ve still got seven kilometres to go. Besides,

there are bound to be more creeks running off these mountains,” he vetoed.

The others grumbled but continued

walking. A large truck roared past powdering them with dust, followed soon

after by a car from the other direction. They passed more new houses of the

suburban type, crossed another creek and went up over a steep little spur which

reduced Roger to heavy panting.

Just over the crest they came to

the railway. They stopped and consulted their maps and studied the line. The

rails were rusty and the sleepers were grey from age and weather but there were

not many weeds. Another vehicle raced by along the road, throwing up more dust.

“The railway,” Graham said

emphatically. He started along it.

Luckily there was a footpath

beside the ballast which made walking easier. The line curved right in a gentle

climb along the side of the mountain.

Dry forest; a mixture

of dense stands of She-Oaks and more open areas of Eucalypts, closed in their

view.

The boys could only see along the line with occasional glimpses of

the mountains ahead.

As soon as they were away from

the road Roger felt a peculiar sense of isolation. The hairs on the back of his

neck stood on end and he had vivid flashbacks to that memorable hike down the

Kuranda Railway two years before.

Stephen spoke up. “Remember when

we walked down the railway from Kuranda?”

“Shut up Steve. I’m trying to

forget that,” Roger replied. He shivered and looked up the mountainside on his

left. It was just ordinary dry bush.

Nothing unusual.

Nothing to worry about.

But he still had the urge to keep

looking behind him and wished he wasn’t last.

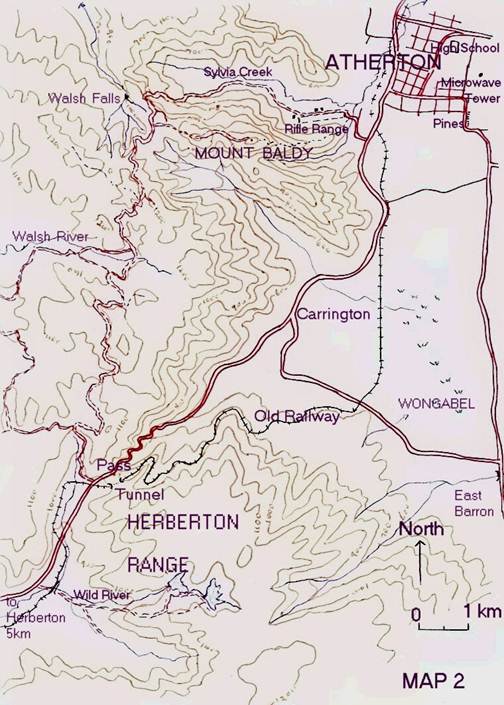

MAP 2: HEBERTON

RANGE & MT. BALDY

For Roger the walk up the railway

became a test of willpower. He seemed to quickly tire and was soon walking in a

sort of zombie-like daze. Frequent trivial obstacles forced him to keep alert: fallen

rocks and clumps of tall grass or small washouts. From time to time the

footpath became so narrow they had to walk between the rails but this was

annoying as the sleepers were unevenly spaced which made it hard to settle into

a rhythm. The sleepers also varied. Some were flat and others rounded. Many

were half-rotted with crumbling interiors or had split and jagged surfaces.

The cadets crossed half a dozen

culverts and small bridges a few metres long but all the streams were dry. Bare

sand and bare rock began to predominate on the surrounding slopes, with

grass-tree and straggly, open bush. The railway curved into a small valley

where there was no breeze at all and the afternoon sun radiated from the

enfolding slopes as from a reflector fireplace.

At the head of this large

re-entrant was a larger bridge, ten metres long. The map showed the stream to

be Carrington Creek. Carrington Falls was the steep rock face on their left but

barely a trickle of unattractive slime was the only water flowing down it. The

disappointed boys stood on the bridge and looked gloomily at it.