Belisarius: The Last Roman General (8 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Allies and Mercenaries

The loss of the traditional heavy cavalry armed with spear and javelins was to some extent offset by the recruitment of

foederati,

unassimilated barbarians armed in their native styles serving under Byzantine command. These included spear-armed troops from the northern frontiers, for example Goths and Heruls, who slowly adopted Byzantine drill, whilst retaining their own distinctive weapons. These troops later formed the nucleus of the Optimates guard unit.

The Byzantines continued to use non-Roman horse archers such as the Huns and other nomadic tribes from the east. These were known as

ethnikoi,

and they appear to have been used as specialist troops, especially where their scouting ability was concerned.

Both foederati

and

ethnikoi

troops became an increasing feature of the Byzantine military system.

The

bucellari

(personal guards) were named after the

bucellatum,

the dried biscuit or hard tack which was issued as rations in the field. They appear to have originally comprised the more heavily-armed barbarian, and especially steppe, nobles and their retainers serving directly under the general who had hired them. As a consequence, the majority were armed with their traditional equipment, namely a

kontos

(lance), a bow and possibly a small shield. (It should

be noted however that the lance, whilst being the requisite length, was never used by the Romans in the couched manner that became prevalent in the later Middle Ages. Instead, it was used underarm and two-handed.) Forming the core of a general’s

comitatus

(‘fellow troops’, ‘personal army’) in the Justinian period, by the time of Belisarius this equipment had become the norm, later spreading to other units of the cavalry.

The

bucellarii

were recruited by the generals under whom they served, not by the emperor, and so had loyalty only to the general that hired them, not to the empire or to the emperor in Constantinople. Although this was a situation fraught with danger for the emperor, there was little that could be done to change things. As mercenaries, they paid for their own equipment before hiring themselves to whoever was willing to pay them, or to generals in places where the chances of plunder were great. They had no desire to become soldiers who were only for show around the emperor.

The reduction in the power and status of the legions, the reliance upon horse archers and the employment of mercenary troops armed in their own fashion marked a distinct phase in the development of the Roman army. In effect, the old Roman army was gone.

Defensive Equipment

Alongside the change in the nature of the army, there was a corresponding change in dress and equipment. It has always been assumed by scholars that the Roman army retained many features throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods. In the earlier empire, the state-owned

fabricae

(factories) manufactured weapons, shields, armour and helmets. These were then distributed around the empire. Furthermore, helmets, body armour, shields and swords would be manufactured to specific patterns, depending upon whether the unit receiving them was a

legio

(legion),

ala

(cavalry) or

auxilia

(non-Roman infantry) unit. Many writers have assumed that the model remained true throughout the empire.

The theory does not take into account a major change in practice in the era approximate to the fall of the west. Earlier, money was deducted from troops’ wages to pay for the equipment that they used. However, Anastasius changed the system in 498 or thereabouts. The soldiers were now paid ‘in full’, but they were expected to equip themselves out of their own purse. The large increase in pay meant that service in the army now became a viable career again; conscription was no longer needed and the army increased in size. The new levels of willing manpower available may have been a factor in Justinian’s attempt to reconquer the west.

It is likely that the equipment that they bought depended upon several factors. Certainly, there was the obligation to fulfil their duties, and in this it is likely that they would purchase offensive weapons consistent with that of their unit, otherwise they would be a liability to their comrades. It is possible that

these were still supplied specifically by the government in order to avoid confusion. It would also be necessary to buy equipment that would identify them as belonging to their unit; either they would have helmet plumes of the same colour or their shields would be painted with a colour or pattern to match that of their colleagues, or both.

Yet within specific limitations, there would be a great deal of flexibility according to their personal tastes. Specific weapons, such as swords, were doubtless bought for individual preference, since weight, length and ‘feel’ are highly individual aspects of weapons. In addition, the more expensive defensive items would not be to everyone’s taste. Helmets and body armour could have been bought and tailored to fit, with the individual having to balance the greater cost of chain mail with its excellent defensive properties against the cheaper but more easily-damaged scale armour. Nor was this all. There was the possibility of using quilted linen armour, or even of relying upon a large shield and having no armour to cover the body at all. Furthermore, in provinces such as Egypt and Spain where there was little danger of military duties, with the troops acting more as a police force, there would have been little incentive for the troops to buy armour which they were never likely to use.

The same factors also apply to helmets. Although it is common to find helmets described as either ‘infantry’ or ‘cavalry’ helmets, it is likely that by the later period covered here there was a considerable overlap of helmet usage between the various services of the army. Since it was down to cost and personal taste, a relatively rich infantryman could probably afford the same helmets – or better – than the less well-off among the cavalry.

Therefore, the common image of units wearing exactly the same equipment should no longer be considered the norm. There was likely to be a variety of helmets, shields and armour within each unit, with only the colours of crests and/or shields defining the parent unit of the soldier. The main limiting factor would be availability. The equipment needed to re-equip the army, following both the defeat at Adrianople and the decision to change the armament of the cavalry, had to be manufactured in eastern

fabricae:

the

fabricae

of the west having by now been lost. This would have greatly reduced production and is likely to have caused shortages in some areas for at least some time.

In light of these considerations, it has been thought best to look at the equipment of the troops by equipment type, rather than by whether it is deemed to be worn by infantry or cavalry units by modern historians and archaeologists.

Helmets

There were a few types of helmet available for the soldier of Belisarius’ army to purchase.

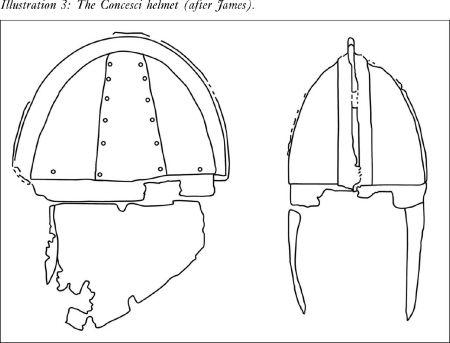

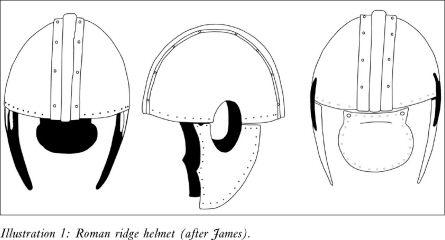

The first types are known as ‘ridge helmets’. Although they came into use as early as the late third century, these types continued in use for a very long time and were probably still in use during the wars of Belisarius: indeed, coins dating between the fourth and sixth centuries depict emperors wearing variants of the type, although this may be due to tradition in the imagery rather than contemporary fashion.

Ridge helmets came in two varieties. The archetype of these is known as ‘Intercisa’, named from the site where the first remains were found. These helmets were constructed from two halves, joined along the centre by a metal strip. There were three varieties of joining strip found on the site. Those of Intercisa 1 and Intercisa 2 were relatively broad and low, that of Intercisa 3 was narrow and high. These differences might simply be ascribed to production techniques and overall design effect of the finished helmet rather than profound differences in manufacture.

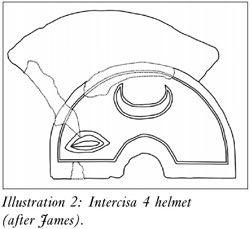

However, on Intercisa 4 the ridge projected far above the bowl of the helmet, forming a large metal crest. In art these metal-crested helmets are shown on various manuscripts, but it is likely that the soldiers portrayed are guardsmen. Therefore the difference between Intercisa 4 and the others may be that this helmet was worn by officers or guardsmen, worn to distinguish them from others in battle. This remains doubtful, however, since some of the Intercisa 1, 2 and 3 helmets appear to have had holes and fittings for the attachment of crests. If this is the case, the large metal crest of Intercisa 4 would have been less noticeable, especially in battlefield conditions.

Finds of similar helmets at Berkasovo were made from either two halves or four quarter pieces, but also include ‘nasals’ to guard the nose. Although such nasals are known from the Classical Greek period, this is unlikely to have represented a return to classical styles. Such patterns were popular amongst peoples from the steppes, such as the Huns, who appear to have been the source for many of the designs in the Byzantine army of this period. A similar example was found at Burgh-on-Sands in England (Plate 17).

The second type of helmet is known as a ‘spangenhelm’, from the German word

spangen,

which was applied to the inverted T-pieces with which such helmets were constructed. The spangenhelm was made from four or six shaped iron plates, attached to a brow band at the base and then connected together at the sides by the aforementioned

spangen,

made from gilded copper-alloy plates. The helmet was surmounted by a disc to hold the completed assembly together.

Unlike earlier helmets, where cheek pieces and neck guards were integral parts of the helmet, in all of these helmets they were made separately and attached to the lower rim of the helmet. This was likely to have been for ease and low cost of production.