Belly of the Beast (18 page)

“I’m a nurse’s aide. I’m trying to save my son.”

“Rutabagas, what am I to believe: Latvian? Canadian? Deaf-mute? Scientist? Nurse’s aide? Wife? Mother? CIA?”

“You forgot retarded,” said Pytor. “Look, I’ve got six bottles of vodka back in Kyshtym and—”

“I’m desperate,” said Niki. “My son is dying. I’ll do anything to save him.”

“Did you kill Vanya to get his truck?”

“Of course not.”

“We just took his place,” said Pytor, “and I really do deliver vegetables. Honest.” He slapped his heart. The dosimeter clicked to life.

“And?”

Pytor turned off the dosimeter. “And I try to document nuclear accidents to save Russian lives.”

“Please,” begged Niki, “Help us. You know what it’s like to lose a child. My son is only thirteen.”

“Sasha was twelve.”

“It could be your way of thanking Yuri Kolchak,” said Pytor.

“This is Mayak. You tried to deceive me. Rules are rules . . . but only if you two are telling the truth would you lie so much. But if you are telling the truth, I have to turn you in. But then again, I’m an old man with nothing left to lose. Quickly, before I change my mind, what are you looking for?”

“My mother worked here, Svetlana Mikhailovna Trepova, did you know her?”

“No. There were thousands of us.”

“What about Joseph Hauser? He was German. He was at Techa.”

“Techa held thousands of prisoners: Germans, Poles, and Russians alike, but they tore all the old barracks down years ago.”

“He was my father,” said Niki. “He may have left a note in a concrete tunnel.”

“Anything written was forbidden, and there are many concrete tunnels. I was an engineer. I helped build some of them. I didn’t know this Joseph Hauser. He’s probably dead. Go home. Be with your son.”

“When we drove in, you said that there were plutonium pipes underneath us,” said Niki.

Borya nodded. “Extracted plutonium slurry.”

“Product 76,” said Niki. “People used to crawl under the pipes to mop up leaks.”

Borya’s eyes lit up. “Product 76. We haven’t used that name in decades. We had to save every spilled drop.”

“My mother indicated it was the Alpha Tunnel.”

Borya took a deep breath. “The Alpha Tunnel. The first, the worst. When the slurry in the pipes was too dry, the pipe plugged. The only way to get it out was to cut the pipes and drag the slurry out bit by bit, and that tunnel wasn’t made for comfort.”

“You know where the cut pipes are?”

“Of course. But you can’t go there.”

“But there may be a note telling me how to find my father.”

“Only a fool would leave a note in such a place.”

“They were in love,” said Niki. “Have you ever been in love?”

Borya put his pistol back in its holster. “The tunnel is sealed. Enormous concrete blocks in both ends like it was supposed to be from the start. You couldn’t move them with a bulldozer. Your search is over.”

“There has to be a way.” Niki choked up. “I’m so close.”

“It’s sealed. No one has been in there for a decade or more. Just as well. It’d probably be hotter than Khrushchev’s temper. Radioactive hot, if you know what I mean. I don’t like to go near the ventilation shaft.”

“A ventilation shaft?” asked Niki hopefully.

“The opening is too small for a man to fit,” said Borya.

“I’m smaller than a man.”

“There was a ladder of sorts, but it’d be crazy to go down there.”

“My son will die if I don’t find my father.”

Pytor took Niki’s hand. “You’ve made this about something it isn’t. It’s against all odds that going into the tunnel and even finding your father will make a difference.”

“I don’t care. It’s Alex’s only chance. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t try.”

“I’ve heard enough,” said Borya. “Drive back toward the gate.”

Pytor did as he was ordered.

I was so close

, thought Niki.

If only—

“Stop here,” said Borya. He got out. Pytor and Niki followed. Borya slowly walked through the soft snow.

“What’s going on?” asked Pytor.

“I know what it’s like to love a child. I’ll show your friend the hole so she’ll realize it’s impossible to get into the tunnel. She can go home knowing she tried her best.”

Snow swirled within the illuminated spheres of building lights, but in a clearing halfway between two old buildings it was dark. Borya thumped his foot as he walked slowly back and forth. When it echoed, he kicked at the snow until his boot sounded on steel. He and Pytor pulled back a heavy cover. Acrid vapors rose from a black hole.

Pytor turned on the dosimeter. It clicked rapidly. “It is the breath of the foul beast,” he said, “but not as radioactive as it could be.”

Niki peered at the hole. It was barely the width of her shoulders. She tried to picture herself squeezing through it, pressed from all sides, a dark void below.

“The shaft used to be covered by a structure with fans to air out the tunnel when workers were inside,” said Borya. “They were in it a lot until the new processing plant was built. When they closed this tunnel, they moved the ventilator building to another tunnel, then welded a steel plate over this shaft. Later, they cut a hole in it just big enough to lower sampling equipment.” He shined his light down. It lit twenty or more loops of steel rebar evenly spaced down the side. Light reflected back from the bottom. “It’s flooded,” he said. “Now you can go home.”

“How deep is the water?” asked Niki.

Borya painted the bottom of the shaft with his light. “Perhaps a few centimeters, perhaps a hundred, but it doesn’t matter. It’s not water. That stuff has to be toxic as hell.”

“I wish I had a sample of it,” said Pytor. “I could document—”

“Document this,” interrupted Borya, “That tunnel is hell itself, and those rungs are the devil’s ladder.”

“Where is the cut pipe?” asked Niki. “They left notes in it.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Pytor.

“I just need to know.”

“She needs to know,” said Borya. “The ladder down the ventilation shaft opens to a narrow walkway along the side of the tunnel. Rows of pipes run along the opposite wall. About ten steps to the right some big valves almost block the passage. A step or two past them, about shoulder high, is the pipe that was cut over thirty years ago. Others were cut just before the tunnel was closed.”

“You remember old details well,” said Pytor.

“The pipes were plugged with uranium slurry. You don’t forget that stuff. Workers cut the pipes with acetylene torches and hauled hundreds of kilos of slurry in buckets in order to salvage a few grams of plutonium. I helped build this tunnel, and I was one of the workers who cut the pipes. It’s amazing I’m still alive; I’ve mopped up my share of Product 76.” He looked into the hole again. “But now I wouldn’t go down there if Boris Yeltsin himself held a gun to my head.” Borya stepped back. “And it

will

be my head if anyone finds us here. Let’s go.”

“I can squeeze through that opening,” said Niki, “and I could climb along the pipes to keep above the stuff on the bottom. I used to climb trees all the time.”

Borya shook his head. “I can’t let you go down there.”

“I could be in and out in five minutes.”

“It would be foolish,” said Pytor, “besides, I’m not sure if this is about your desperate desire to save your son or your personal fear of failure.”

“If you thought there was a chance in a million to bring back Irina, would you go?” asked Niki.

“Five minutes is too long,” said Borya.

“I have on boots,” said Niki. “If the water’s not deep, I’ll dash to the cut pipe and be back here in two minutes. I can hold my breath that long.”

Pytor looked down at his wife’s boots in the dim light. “Irina’s boots aren’t waterproof, that’s not water down there, and you’ll be breathing harder than ever. I can’t let you go.”

“It’s not your decision to make,” said Niki.

Borya scratched his chin. “Two minutes wouldn’t be too bad. Heaven knows I’ve been in there for hours.”

“At least take the dosimeter,” said Pytor. “If it sounds anything like it did on the lake bed, get out as fast as you can. Promise me.”

Niki nodded. “I promise.” She put the dosimeter in her coat pocket and then turned to Borya. “May I borrow your light? I’ll have it back to you before you know it, and we’ll be out the front gate in five minutes.”

Borya handed Niki his light.

“I care very much about you,” Pytor said to Niki. “I don’t like this one bit.”

Niki smiled as best she could and gave Pytor a quick kiss on the cheek. “I’m a survivor,” she said a she stuffed the lavender gloves in her right pocket on top of the dosimeter.

“Three minutes,” said Pytor as Niki sat on the snow and lowered her feet into the opening. “Any longer and I’ll come in after you.”

Niki knew there was no way Pytor could fit through the small opening. She studied the passageway a moment and realized she’d need both hands to lower herself. “I’ll use the light once I’m on the bottom. Hand it to me once I’m inside.” Niki rolled to her stomach and slid her legs fully into the shaft. She felt the first rung with her left foot, then lowered her right foot to the next and wiggled her coat and arms past the rim. She felt it press Katrina’s ski medal against her chest. Only her head stuck above the snowy ground as Pytor handed her the light.

A car engine groaned somewhere out of sight.

“Someone is coming,” Borya said frantically. “We’ve got to get out of here.” He held out his hand for Niki. She ducked out of sight.

“Women!” he said in frustration. He turned to Pytor. “That milk truck shouldn’t be here. Drive me to the gate, but leave the lights off. You can come back for Niki on foot in a minute or two.”

“I’ll be back,” Pytor yelled to Niki.

As the milk truck went out of sight toward the entry gates, headlights appeared from the opposite side of the clearing.

Niki eased down another step. The acrid air caught in her throat. Confined. Unable to breathe. It was Niki’s worst nightmare.

I can’t do this

, she said to herself. Eyes closed, her memory flashed back to an overturned jeep in the San Juan River. Niki saw the rolled-back eyes of the drowned girl as she was wheeled toward the morgue.

I cannot fail again.

With a fresh wave of determination, Niki lowered herself another rung. The pitted steel rungs dug into her hands. She reached into her pocket for her gloves and touched the dosimeter. It shrieked to life. She yanked it out, and tried to turn it off in the dark with one hand. Impossible. Ears ringing, she asked herself,

Did you think this would be easy?

Niki banged the dosimeter against the concrete wall; it continued to screech its alarm. Niki let it fall.

In a second, the dosimeter’s noise ended in a splash.

With claustrophobia dissolved in adrenaline, Niki felt for her gloves, but only found one. She put it on her right hand and descended the ladder in darkness, quickly probing for each foot and hand hold. The lower rungs were more pitted, digging sharply into her left hand.

Niki lowered her right foot for the next step but it moved with her weight. Thinking she must be close, she lowered her foot further, half expecting to touch the fluid at the bottom. Nothing. She put her foot back on the rung and added weight. It held until she moved her left foot from the rung above.

The right side of the pitted metal gave way.

Niki’s body dropped as the rung bent straight down, but she held on with her left hand, shredding her fingers and almost wrenching her arm from her shoulder. She pulled herself up until her right foot rested on the high side of the broken rung.

That had to be the last step

, she thought. Hanging on with her sore left arm, Niki carefully pulled the flashlight from her right pocket.

The surface of some primeval fluid was a body length below; nothing indicated its depth. The bottom rung or two were missing. Niki looked toward the pipes on the opposite wall. The top pipe was below her feet. Considering if she could reach it, Niki shifted her weight to ease the strain on her left arm.

There was no warning when the rest of the step gave way.

Niki’s left hand jerked from its hold. The jagged iron point of the broken step tore through her calf. Niki’s scream filled the tunnel as she hit the bottom. The light glowed for a moment, then disappeared.

Niki landed on her feet, but wildfire raced up her right leg. She felt where the step had ripped open her pants and her calf. Warm blood oozed into her boot from above; cold fluid soaked her boot from below.

At least that shit wasn’t deep.

I’ve got to stop the bleeding.

From her medical training, Niki knew to apply pressure. In the dark, she took off her remaining glove and folded it tightly against her wound. She used the lanyard from Katrina’s medal to hold it in place. More adrenalin sped her thoughts.

Get the note and get out.

Standing on her good leg, Niki moved her right foot in an increasing radius trying to find the light. She felt the square edges of the dosimeter and the curved rebar of the broken ladder rung. She felt something half floating. The lost glove.

Damn, I am always losing things.

Frantically, she widened her circle but her foot hit a pipe before she found the light. She reached out and found another pipe shoulder high.

Mother crawled under these pipes, went through worse to try to save me.

No wonder she was crazy.

In that moment, Niki withdrew the thorn in her brain that was her mother. Her head cleared. She knew where she was and what she had to do. The pipes were right where Borya said they would be.

Giving up on the light, Niki felt her way down the tunnel, counting each painful step. The fluid was less deep at nine steps; valves almost blocked her way at thirteen. The floor dried between fifteen and sixteen.

With her hand running along the shoulder high pipe, Niki took four more steps. The pipe ended, cut off, shoulder high, again just like Borya had said. Niki reached inside to her wrist, to her elbow, to her shoulder.

Nothing.

There was no cylinder, no note. Niki dropped to her knees in the God-forsaken pit. Hot embers seared her leg

. I should have listened to Rob, to Yuri, to Pytor.

I’m so stupid.

Dying seemed preferable to going back without the note. “I love you, Alex,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry. I’ve failed you.”

Niki pictured him, a small baby cradled in her arms, his first tiny steps, his first—

In the darkness, Niki’s eyes shot open. Borya said ten steps to the valves. I took thirteen.

Maybe he didn’t remember, but I am smaller. A pipe shoulder high to him would be head high for me.

Niki stood and reached to a higher pipe, then walked back toward the valves. Fingers flying, Niki felt a cutout section but, because of her height, could only reach elbow deep and there was nothing on either side. She had to get higher.

With her left foot balanced on a lower pipe, Niki pulled herself up and slid her arm all the way into one side of the rough pipe. It was there, a pint-sized canister, a bit of hope in the most hopeless place on earth.

Fingers tingling, Niki pulled out the canister and stepped back to the floor. She felt the top but thought better of trying to open it in the dark. Instead, she squeezed it into her coat pocket and started back.

At eight steps, Niki stepped on something soft.

The glove. I must have miscounted. I would have gone too far if I hadn’t dropped it.

Niki turned, felt for what was left of the steps, and stepped on a small cylinder.

The light.

Thank God for small blessings.

Carefully, she pushed it toward the wall, tipped it up with her boot, and grabbed the end with her thumb and forefinger. She let the light drain a second, then felt for a switch, flicked it on, then off, then on again. Nothing. In frustration, Niki flung it.

As it hit the wall, a beam of light burst from its end, lit the rusty pipes, then lit the wall itself as it swung in a circle on its way to the floor. After a splash, the light glowed beneath the surface. Niki grabbed it. Crusty green fluid burned the back of her hand. It didn’t matter anymore. She turned and painted the ladder with light.

Jagged remnants of iron spotted the wall where the lower rungs had been. Above, the lowest remaining rung was beyond reach, beyond jumping. “Pytor,” she yelled toward the shaft.

There was no answer.

Niki was beyond hope. She lowered the light.

At least I need to know if there was a note.

She took the cylinder from her coat pocket. It was a small version of Rob’s stainless thermos bottle, but tarnished black. With the light held tightly under her arm, Niki tried to unscrew the top, left and right. It wouldn’t budge. She turned it over for better leverage and spotted a small screw in the bottom. She broke a fingernail trying to turn it.

Niki all but sat down in the radioactive sludge, then decided to take one last look at her son. As she pulled out the envelope, she felt the quarter, her last connection with a county a world away. The light flickered. Rob had adjusted the carburetor on her truck with a dime one time. With the quarter, Niki turned the screw and released a hiss of air. The canister opened easily after that, and Niki extracted a slip of paper, well-aged, but the Cyrillic characters were still legible.

Returned to Mayak,

she read before tears blurred her vision. Niki put the note into the envelope with Alex’s picture and slid it inside her shirt next to her heart. As her vision returned, she looked at the quarter.

1991, In God We Trust.

Niki dropped it. Green stuff splashed against the braided cord that held her glove about her leg. She looked at the cord, then at the first rung.

I didn’t come this far to give up.

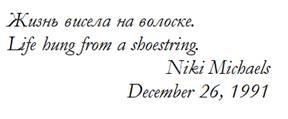

Niki set the canister on the lower pipe and untied her makeshift compress. With the bloody glove as a cushion, she balanced the light next to the canister and unbraided the parachute cord, being careful not to drop Katrina’s medal. Finally, she tied the ends of the three strands together with the medallion tied at one end. It was not much more than a long shoestring with a brass weight at one end.

It took three throws before the brass medallion wrapped itself about the iron loop of the lowest rung. Niki tugged on it, expecting it to break or pull free. The parachute cord held.

Niki grabbed the light to study the footholds and was about to start up when she thought about the cylinder. Pytor came all this way for nothing. It would only take a second to scoop up a sample.

The green fluid stung her hands again as she half-filled the little cylinder, closed it, and pushed it back into her right pocket. She put the light in her left pocket with the light beam shining out.

With adrenaline coursing wildly through every muscle, Niki wrapped the cord around her hand and half-jumped, half-pulled, and half-scratched her way up to the first solid rung. Niki knew she could make it the rest of the way and took another second to unwrap the medallion and drop it inside her shirt with the envelope.

Cold air and falling snow met Niki as she worked her way back toward the surface. “Pytor?” she asked as she poked her head out into the glare of headlights.

“Get out!”

Niki turned to face the barrel of a gun.