Between Gods: A Memoir (27 page)

Read Between Gods: A Memoir Online

Authors: Alison Pick

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Religion, #Judaism, #Rituals & Practice, #Women

He tells me about his own trip to the Pinkas Synagogue. As he talks, I recall how the names covering every square inch of the walls are written in tiny cursive script barely legible to the

naked eye. But Degan entered the room, raised his face, and the names jumped out at him, as though Oskar and Marianne themselves were waving hello.

“Wow,” I say.

“I know.”

“I also saw an Irma Pick. That was your Gumper’s sister, right?”

“Really? I didn’t see her!”

Alone in the hush of the room, Degan recited the Kaddish. Whereas when I was there, the place was full of tourists.

We brush our teeth—the toothpaste makes me gag, the feel of the bristles against my back molars, and flossing is out of the question—and collapse into bed. I sleep for thirteen hours, unmoving, like a corpse. The following day we take the train to Auschwitz.

twenty-three

S

EEING THINGS THROUGH THE LENS

of cinema is a cliché of North American culture, but all I can think about as we board the train to the death camp is who should score the soundtrack and who the starring actress should be. It’s late afternoon, and a violently bloody sunset streaks the sky. The set designers add a last layer of red. The trip takes several hours, the train left over from the Cold War era: metal, utilitarian, and almost empty. The slow rocking of the carriage makes me gag. The closer we get to our destination, the slower we move. The laboured clacking of the wheels over the tracks is audible:

ca-lunk, ca-lunk, ca-lunk

. At the penultimate stop, a bald tattoed man in tall lace-up neo-Nazi boots boards. He sits in the seat across from us, eyes forward. As the train starts to move again, I look out the window and see an abandoned gravel lot, and standing at its border, three

gaunt children in tattered overalls, holding up their cameras to take our picture.

It is, of course, impossible to travel on a train to Auschwitz and not think of others who did so in different circumstances. It is summer now, and warm, but in her video interview, Vera says that she and her family were sent on December 17. I try to imagine the cold, but my mind trips and falls. They didn’t sit for three days. Her children clung to her. They were jammed into a freight car, with one bucket to use for a toilet for a hundred people. People were sick. People died.

It was night when they arrived. There were SS men, dogs, people in striped pyjamas, Nazis yelling, “

Raus! Raus!

” “It was a scene from a madhouse,” Vera said. “Yelling. Beating. You didn’t know where you were.”

The men and the women were separated on the platform. I imagine little Eva, gripping the edge of her mother’s dress. What is a five-year-old like? She needs help cutting her meat. A story before bed, the sheets tucked up around her chin. She is bright enough, smart enough to understand the adult world around her. You can see the first signs of the person she’ll grow into, but she still has the smell of a baby about her.

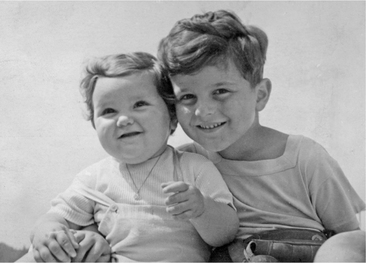

Eva had curls and big cheeks. She was born in the unlucky year of 1938. She held her mother’s hand as they were loaded into the back of a truck. They were beside a woman Vera knew who had been a prisoner for some time. The woman said, “You’re in Auschwitz. We’re all going up that chimney.”

Vera says to the interviewer, “We didn’t understand.”

The next morning they were sent to the showers. Those little spiked nozzles on the ceiling, so portentous. But it was water that rained briefly down on them. Naked, in December,

tiny Eva shivering. I picture her thin arms, the way her small shoulder blades would have jutted from her back like wings. The prisoners had been forced to leave their clothes on a peg outside; at the end of the shower, their belongings were gone. There was only a huge pile of other people’s clothes. They scavenged to find something to wear. Vera tears up. “I was glad I found clothes for little Eva. I was so worried she would catch cold.”

Later they stood in line to get tattooed. Vera pulls up her sleeve as proof, to the interviewer, to the part of herself that still refuses to believe.

“Was it painful?”

Vera doesn’t answer. “Eva was very smart,” she says, instead. “Some of the children were crying terribly, but she didn’t cry.” Her daughter understood not to make a fuss, in case compliance could help them.

Vera’s number was 71251.

Her little daughter Eva’s was 71252.

I try to imagine, as though I am there, Eva pulling up her sleeve. The fabric getting caught, bunching up. Maybe Vera had to help her, holding her daughter’s arm steady under the pain. Little Eva clenching her milk teeth while the hot needle burned into her skin.

A five-year-old still likes to hold hands.

Tears roll freely down Vera’s cheeks as she remembers. Midwinter, in Auschwitz, a friend of Vera’s brought Eva a gift. It was a tiny stuffed toy, sewn from a scrap of old cloth. A little mouse.

Vera’s tears are for the smallness of this pleasure, and for its enormity. For the generosity of her friend in the face of the unthinkable. Tears remembering her daughter’s real delight. That her daughter

could

be delighted in such circumstances. That she will never be delighted again.

When the train stops at Auschwitz, Degan and I are the only ones who dismount. The station is abandoned. We walk around aimlessly, looking for a taxi; the driver we eventually find doesn’t speak a word of English. Only through a crudely acted pantomime of execution, a finger slit across the neck, are we able to tell him where he should take us. Our hotel is located directly opposite the camp gates. We can see the infamous wrought-iron slogan,

ARBEIT MACHT FREI

—“work sets you free”—from the lobby. The man who greets us at reception has one arm.

Like college roommates, Degan and I fall into the twin beds and a deep, unconscious slumber, and wake to a world where anything could happen. “Maybe we should just forget it,” I say. “Relax in the hotel and watch TV.”

A joke: there’s no TV. And Degan is already putting on his nicest shirt and tie: he wants to dress up to honour my family.

It’s a grey, rainy morning at the world’s most infamous death camp. Tourists of all ethnicities mill about. We join a four-hour English walking tour and are herded around, a mass of humanity, which I can’t help but find ironic. A large man in sweatpants drops an empty nachos bag casually on the floor of one of the barracks. Our guide shows us all manner of gas and execution chambers, piles of shoes, piles of human hair, Zyklon B crystals, graphic photographs demonstrating the results of Dr. Mengele’s “medical experiments.” Eighty per cent of the people getting off the train, we are told, were sent directly to the gas chambers.

Oskar and Marianne were among them.

Vera and her children were not.

Auschwitz, I remember Rabbi Klein telling us, is sometimes seen as the inverse of Mount Sinai. Receiving the Ten

Commandments was the time we were closest to God. And here at Auschwitz—I look around at the size of it—when we were the farthest.

I keep the button on my jeans undone out of necessity, periodically touching my belly. “My little baby. Oh!” I hum to our daughter. Degan bends down and whispers, “Hello, little blastocyst.” The movie-set quality of the tour recedes only once, in the face of a display case of baby clothes. Two or three cloth diapers, a moth-eaten sweater and a pair of tiny booties, their owner long flown to heaven’s angels.

I search for Eva’s tiny stuffed mouse, believing I might actually find it there.

At Birkenau we walk beneath the famous guard tower, then down the railway tracks to the gas chambers. This is where the real killing took place.

Eva.

Jan.

Oskar.

Marianne.

We sit against the base of one of the chimneys and, for the second time, recite the Kaddish: “May His great Name grow exalted and sanctified,” I stumble, “in the world that He created as He willed.”

PART III

The truth is the thing I invented so I could live

.

—Nicole Krauss

one

A

UGUST IS ON THE VERGE

of expiring by the time we arrive back in Toronto. Degan will be busy preparing for the new semester, so I fly on alone to Quebec to tell my parents the news. “Why are you smiling?” Dad asks when we see each other at the baggage carousel.

“No reason.”

I touch my stomach unconsciously.

I’ve decided to wait until we get back to the house in North Hatley—a two-hour drive—so I can tell him and Mum together, but as soon as my suitcase is in the trunk of the car and Dad starts easing out of the parking garage, I blurt it out: “I’m pregnant!”

Dad slams on the brake.

“That’ll be twenty-five dollars, sir,” says the man in the booth.

Dad says, “But you just got married!”

“Three

months

ago.”

“Sir?” the man in the booth says. “There are other cars behind you.”

Dad pays, forgetting his change, and we move out into the turning lane, his face strained with some emotion I can’t read.

“Aren’t you happy?” I ask.

“I

am

happy,” he says, and like magic, the smile on his face grows. “I’m delighted! But I wasn’t expecting it yet. I guess it makes me feel old.”

“Me, too. I’m an adult.”

Dad laughs. “When’s the baby due?”

“March,” I tell him.

“I’ll cancel my Taos ski trip,” he says, now really excited, on board and eager to do whatever he can to help.

I fall asleep almost as soon as we hit the highway and wake up, two hours later, in North Hatley. I’ve been coming here my whole life, but the beauty surprises me every time. The fields and farmland, the picturesque red barns giving way to the enormous summer houses nestled in the woods around the water. The lake spills its shimmer of blue below the rolling hills. We pull up our long gravel driveway. Mum comes out to meet us, stands beside the swimming pool in her bathing suit cover-up, with her sunglasses pushed back on her head. I give her a hard hug. “Alison has some news,” Dad says.

She looks at me expectantly, her eyebrows raised, her skin tanned and sun-flecked from hours on the tennis court.

“I’m pregnant!”

Her eyes widen. “You just got married!”

From inside the house the dog starts to bark.

“Three months ago,” I say.

Mum’s face is blank, registering her shock.

“Aren’t you happy?

“I

am

.” Et cetera.

Those two are meant for each other.

When the routine is completed for the second time, I need to lie down. I climb the stairs to the blue room with twin beds that was my father’s as a teenager. Granny and Gumper built this house in 1966 and it is full of their belongings from the Old Country. The framed maps of Bohemia, the enormous dark wood armoire. Granny’s parents didn’t escape themselves, but managed to send a large amount of furniture out of occupied Czechoslovakia. It spent the war in two containers in Antwerp. When the furniture arrived and was unpacked, the empty containers were so big that Gumper gave them to friends, one to be used for a hunting camp and the other for a garage.