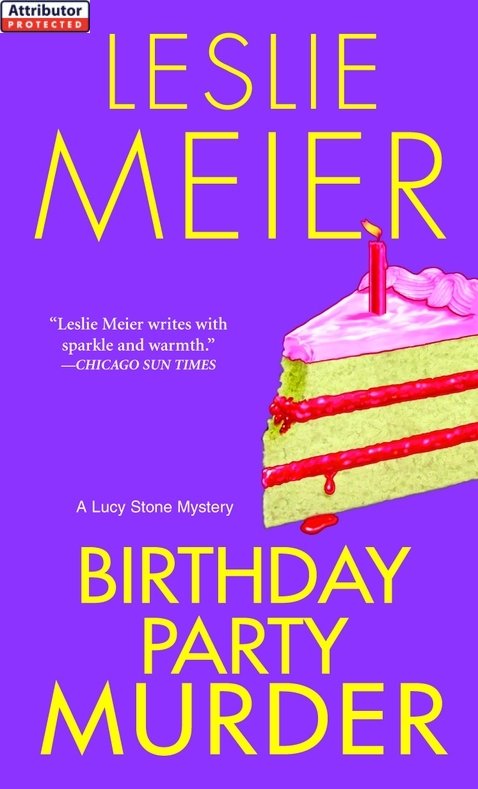

Birthday Party Murder

Read Birthday Party Murder Online

Authors: Leslie Meier

IN SEARCH OF A KILLER

Lucy poked her head into Bob's office. “Bob? I'm done here, but I'd like to look at Sherman's house. Is that okay?”

“Good idea,” said Bob, opening his drawer. “I've got a set of his keys here. It's on Oak Street, number 202.”

“Thanks,” said Lucy, taking the keys.

“I'm the one who should thank you,” said Bob. “I really appreciate what you're doing.”

“I don't know what Rachel told you, but I'm not a professional investigator. There's no guarantee that I'll be able to figure out what happened.”

“I know, I know,” said Bob.

“I just don't want you to get your hopes up,” she said, meeting his eyes. “You've got to face the fact that you may never know what happened.”

He nodded.

Lucy sighed. “And if he was murdered, well, you've got to realize that most murder victims are killed by someone they know.”

Bob swallowed hard. “By someone I know?”

“Most likely,” said Lucy. “Do you still want me to go ahead?”

Bob looked her straight in the eye. “Absolutely,” he said.

“Okay,” agreed Lucy, but as she limped down the steps to the parking area she wished she had a little more to go on than a gut feeling that Sherman Cobb hadn't committed suicide . . .

Books by Leslie Meier

MISTLETOE MURDER

Â

TIPPY TOE MURDER

Â

TRICK OR TREAT MURDER

Â

BACK TO SCHOOL MURDER

Â

VALENTINE MURDER

Â

CHRISTMAS COOKIE MURDER

Â

TURKEY DAY MURDER

Â

WEDDING DAY MURDER

Â

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

Â

FATHER'S DAY MURDER

Â

STAR SPANGLED MURDER

Â

NEW YEAR'S EVE MURDER

Â

BAKE SALE MURDER

Â

CANDY CANE MURDER

Â

ST. PATRICK'S DAY MURDER

Â

MOTHER'S DAY MURDER

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

A Lucy Stone Mystery

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

Leslie Meier

Kensington Publishing Corp.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

IN SEARCH OF A KILLER

Books by Leslie Meier

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Copyright Page

Books by Leslie Meier

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Copyright Page

For my cousin Margery Baird

Chapter One

S

herman Cobb wasn't feeling well. In fact, he hadn't been feeling well for quite some time. He couldn't even remember the last time he woke up in the morning feeling rested and refreshed, ready to face whatever the new day brought. That was why he was sitting in Doc Ryder's waiting room, expecting the worst.

herman Cobb wasn't feeling well. In fact, he hadn't been feeling well for quite some time. He couldn't even remember the last time he woke up in the morning feeling rested and refreshed, ready to face whatever the new day brought. That was why he was sitting in Doc Ryder's waiting room, expecting the worst.

He'd first visited the doctor a few weeks ago, complaining of pain and tiredness. “Ordinary enough symptoms,” Doc Ryder had said in a reassuring tone of voice. But when the doctor palpated his abdomen, Sherman was sure he'd noticed an expression of alarm flicker across his face. It was quickly suppressed, but Sherman had noticed it and Doc Ryder's usually brusque and hearty tone became cautious and guarded as he ordered a battery of tests. “Nothing to worry aboutâjust to be on the safe side,” he'd said, but Sherman hadn't believed him.

Deep inside, he knew something was wrong, just like some women can tell they're pregnant long before the strip turns blue on a pregnancy kit. He didn't know how he knew, but he could feel death overtaking him, like the gradual chill you feel when the furnace goes out. First your hands and feet feel cold; then you notice you can't seem to get warm and the radiator feels cool to the touch. You check the thermostat and notice the temperature has fallen a few degrees; the oil tank must be empty or perhaps the pilot light has blown out. You go down to the cellar to investigate.

That's what he'd done. He'd come to the doctor to find out what was wrong. But no matter what it turned out to be, he knew it wouldn't make any difference. His pilot light was struggling to stay lit, but he knew it was just a matter of time before he finally ran out of fuel.

He sighed and reminded himself that he'd cheated the grim reaper a few times in his life and could hardly complain that his chit had finally come due. He'd had a good life, a productive life. He'd had his share of success; he'd known great happiness. All told, he thought, there was only one thing that he wished had been different.

Maybe it could be, he thought, wondering whether he should simply leave things be or should try to change them after all these years. And if he did, would there be enough time?

Â

Â

Pausing at the kitchen door with an armful of lilac blossoms she had just cut, Julia Tilley realized Papa was angry about something. In her twenty years she had become an expert reader of his moods, always watching for the slightest flicker of his mustache, the curl of his mouth and the lowering of his brows. Not that such acute awareness was required todayâshe could hear his voice reverberating through the entire house, like thunder.

Julia hesitated, unsure what to do. The lilacs would certainly wilt unless she got them into water very soon. On the other hand, Papa's anger seemed to be directed to her older sister, Harriet, and Julia was content to leave it that way. She certainly didn't want to draw his attention by going inside the house.

Moving quickly, she picked up the old enamel bucket that held kitchen scraps and carried it out to the compost heap next to the garden, where she emptied it. She then took it to the pump and filled it with clean water for the lilacs. She set them in the shade and sat down on the porch steps, wondering what to do for the duration. She could walk down the drive to the mailbox, hoping Papa's tantrum would be over by the time she returned, or she could stay here on the stoop andâwell, not exactly eavesdrop because that would be wrong, like opening someone's mailâbut perhaps a phrase or two would come to her and she could figure out what all the fuss was about.

“Damned scoundrel . . . a Communist . . . filthy New Dealer . . .”

So, it was about Thomas O'Rourke, the young man her sister Harriet had been seeing. Julia had suspected as much. He was a labor organizer and a big supporter of Mr. Roosevelt's New Deal. Papa, a Maine Republican, had no doubt that Mr. Roosevelt's policies would ruin the country.

“I love him, Papa, and you're not going to stop me.”

Julia's eyebrows shot up in amazement. Harriet was daring to argue with Papa.

“Don't you dare talk to me like that, young lady,” was Papa's predictable response.

“I'm not young, Papa, don't you see? I'm thirty years old. I've always done what you said and what has it gotten me? I'm an old maidâtoo good for anyone in this town, that's for sure.”

Julia considered this. It was true, she realized, with a jolt. None of the farmers and small tradesmen who lived in Tinker's Cove would want a college-educated wife like Harriet. Or herself, for that matter.

“Is that what you want? To marry some man and become his laundress, his cook, his concubine?” Papa practically spat out the words.

On the stoop, Julia hugged herself. She could see Papa's expression as clearly as if she were the object of his wrath. The bristly eyebrows, the narrow nose and hollow cheeks, the frowning mouth. How could Harriet bear to confront him? How could she stand his disapproval?

“Yes, Papa,” replied Harriet, coolly. “That's exactly what I want, more than anything. I want to feel Thomas's arms around me, his lips pressed against mine. I want to give myself to him. I want to bear his children.”

Julia's jaw dropped, and apparently, so did Papa's. There was silence. A long silence. Julia sat very still, watching the swallows' swooping flight above the neat rows of baby lettuce in the vegetable garden.

When Papa finally spoke, his voice was as cold and hard as ice.

“Understand this: If you marry Thomas O'Rourke, you are no daughter of mine and you will have nothing that is mine. Marry him and you will become dead to me.”

Julia's lips twitched, hearing the awful words.

Â

Â

Rachel reached out to gently shake Julia awake, but hesitated. Miss Tilley was almost ninety years old and, like a lot of very old people, didn't sleep well at night. It seemed a shame to disturb her, even if lunch was ready. She had made up her mind to turn down the pot when Miss Tilley's eyes sprang open.

“Ah, you're awake,” said Rachel. “Are you ready for lunch? It's your favorite, shrimp wiggle on toast.”

Julia Ward Howe Tilley blinked and looked around. She'd been dozing, she realized. Papa was long gone, and dear Mama. And Harriet was dead, too. Julia stroked her arthritic fingers and furrowed her brow. She was the only survivor, the last remaining member of her family. Or was she? What if Harriet had given Thomas O'Rourke a child? Her heart beat a little faster at the thought.

Other books

Flidoring The Early Wars by Hayes, Roger W.

twice cursed mage 05 - claimed by cipriano, j a

Letter from my Father by Dasia Black

Heart of Steel by Jennifer Probst

Half-Assed by Jennette Fulda

The Trespass by Scott Hunter

Quite Ugly One Morning by Brookmyre, Christopher

The Mystery of Adventure Island by Paul Moxham

Sons of Destiny Prequel Series 003 - The Shifter by Jean Johnson

Larissa Learns to Breathe by Ruby Laska