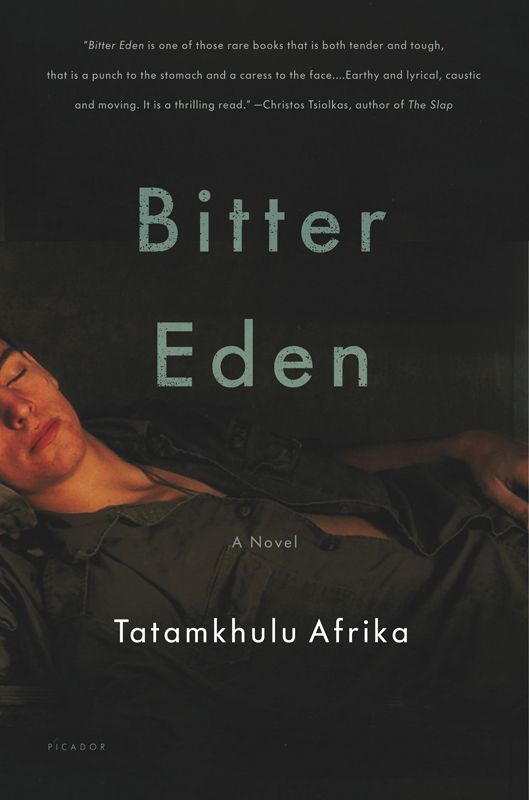

Bitter Eden: A Novel

Read Bitter Eden: A Novel Online

Authors: Tatamkhulu Afrika

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For Tony and Johan who cared when none else did.

Contents

A Note from the Publisher

It would not

seem appropriate to bring you the extraordinary

Bitter Eden

without a few words about its equally remarkable and uncommon author, Tatamkhulu “Tata” Afrika. Tata was a man one might be forgiven for mythologizing, whose fierce values and personal complexity are almost as fascinating as his literary legacy. But to know something about his life only makes the reading of this semi-autobiographical novel that much more enchanting.

Born Mogamed Fu’ad Nasif in Egypt in 1920 to an Egyptian father and Turkish mother, Tata moved to South Africa as a young child, whereupon his parents both died of the flu in quick succession. He was orphaned, adopted by foster parents, and given his second (of an eventual five) names. Precociously, he wrote a novel at age seventeen, which was picked up by the venerable Hutchinson publishing house in London. Regrettably, the book never reached a readership, as the publisher’s offices were bombed in the Blitz, destroying all but two copies of the book’s first print run.

Sent to fight for South Africa in the North African Campaign during World War II, Tata was captured at Tobruk and held in POW camps in Italy and Germany for the duration of the war; it was an experience he internalized with such clarity that it became the foundation of this book, written almost half a century later. It’s worth noting that he also penned a novel while incarcerated about life in the camp, but it was confiscated by the guards once discovered.

Following his release after the war ended, he lived in Namibia and was, among other things, a miner, a barman, a shop assistant, a bookkeeper, and a jazz drummer. In 1964, he moved to his last home, Cape Town, where he converted to Islam—arriving at his penultimate legal name—and became passionately engaged in the battle against apartheid. As the son of Turkish and Egyptian parents, he could have identified as white and spared himself, but he rejected this more comfortable option. He instead joined up with Umkhonto we Sizwe, the combatant arm of the African National Congress, from whom he would draw a pension until his death. He was arrested and charged for his revolutionary activities in 1987 and was listed as a “banned” person for five years.

He began writing in earnest in his sixties, publishing poetry (in contravention of his banning) under his final name, Tatamkhulu Afrika (literally “Grandfather Africa”), winning a number of prestigious awards and critical praise for his work. But it wasn’t until 2002 that his novel

Bitter Eden

was published in the United Kingdom to critical acclaim, with Mark Simpson of

The Independent

choosing it as one of the best two books of the year. Tata was eighty-two at the time. He died two weeks later.

Tata’s posthumous acclaim for

Bitter Eden

was accomplished with the help of a circle of fierce advocates and friends in South Africa, including Robin Malan, who helped him type the manuscript when his eyesight failed, his poetry publisher, Gus Ferguson, and his South African agent in London, Isobel Dixon. A decade after the book’s first publication in the United Kingdom, the novel has found a growing circle of admirers, including such prize-winning authors as Booker finalist Christos Tsiolkos and André Aciman. We hope that you are held rapt by the dark and brutal, but intensely intimate, portrayal of men forced together in war, and the wounds that don’t heal once guns are laid down.

So, much like the tangled paths of Tata’s embattled but rich life, this book has wended its way into your hands. Picador is pleased to finally be able to share with you

Bitter Eden

and we hope that you will agree that you have within these pages a true classic.

I touch the

scar on my cheek and it flinches as though the long-dead tissue had a Lazarus-life of its own.

Uneasily, I stare at the two letters and accompanying neat package which are still where I put them earlier in the day. Within easy reach of my hand, they are a constant and unsettling focus for my mind and eye.

The single envelope in which the letters were posted is also still there. Airmail and drably English in its design, its difference from its local kin both fascinates and disturbs. I am not accustomed any more to receiving mail from abroad.

The one letter, typed under the logo of a firm of lawyers, is a covering letter which starts off by describing how they have only managed to trace me after much trouble and expense, which expense is to be defrayed by the ‘deceased’s estate’. Then comes the bald statement that it is

he

that has ‘passed on’ – how I hate that phrase! – after a long illness whose nature they do not disclose and that I have been named in his will as one of the heirs. My legacy, they add, is very small but will no doubt be of some significance to

me

and it is being forwarded under separate cover per registered mail.

The other letter is from him and I knew that straight away. After fifty years of silence, there was still no mistaking the rounded, bold and generously sprawling hand. Closer inspection betrayed the slight shakiness that is beginning to taint my own hand, and I noted this with an unwilling tenderness and a resurgence – as unwilling – of a love that time, it seems, has

too

lightly overlaid.

After reading the letters – but not yet opening the package – I had sat for a long time, staring out of the window and watching gulls and papers whirling up out of the southeaster-ridden street, but not knowing which were papers and which were gulls. Reaching for an expected pain, I had found only a numbness transcending pain and, later, Carina had come in and laid her hands on my shoulders and asked, her voice as pale and anxious as her hands, ‘Anything wrong?’

I do not mean to be disparaging when I refer to Carina in these terms. I am, after all, not much darker than her and although my hair is fair turned white and hers is white-blonde turned white, my body hair is as colourless and (as far as I am concerned) unflatteringly rare. I, too, can be nervy although not as pathologically so as Carina whose twitchiness sometimes reminds me of the dainty tremblings of a mouse – and that despite the fact that she moves her long, rather heavy bones in a manner that is unsettlingly male.

Do I love her? ‘Love’ is a word that frightens me in the way that these two letters frighten me and if I were to say ‘yes’, I would qualify that by adding that – in our case and from my side – love is an emotion too often threatened by ennui to attain to the grand passion for which I have long since ceased to hope.

Certainly, though, I loved her enough to be able to say, ‘No, everything is fine,’ and turn around and smile into the once so startling blue eyes that now – under certain lights and when looked at in a certain way – have faded into the almost as startling white stare of the blind.

Whether she believed me or not, I cannot say, and equally do I not know why I have bothered to even mention a wife, and a second one at that – the first having absconded to fleshlier fields a lifetime ago – who does not in any way figure in the now so distant and tangled happenings with which the letters deal. Or do I, indeed, know why and have I subconsciously allowed Carina to surface in a manner and image that have more to do with me than her and that will save me the pain of having to explain in so many words why, in those years of warping and war, an oddness in my psyche became set in stone?

Whatever the case, I am now back with the package and the letters, leaving Carina sleeping – or pretending to, she being disconcertingly perceptive at times – and no commonplace papers or gulls beyond the window to divert me: only a darkness that is as inward as it is outward as – yielding to the persuasion of the tide I thought had ebbed beyond recall – I turn to the package and start to unwrap it, then stop, not wanting this from him and as afraid of it as though it held his severed hand.

Or is this all fancifulness? Am I permitting a phantom a power that belongs to me alone? What relevance do they still have – a war that time has tamed into the damp squib of every other war, a love whose strangeness is best left buried where it lies?

Haplessly, unable to resist, I listen for the nightingale that will never sing again, hear only the screaming of an ambulance or a patrol car, a woman crying to deaf ears of a murder or a raping in a lane, and lower my face into the emptiness of my hands.

* * *

I am lying

on the only patch of improbable grass in a corner of the camp. Balding in parts, overgrown in others, generally neglected and forlorn, it is none the less grass, gentle to the touch, sweet on the tongue. The odd wild flower glows like a light left on under the alien sun.

I am not alone. Bodies, ranging from teak to white-worm, lie scattered at angles as though a bomb had flung them there. As at a signal, conversations swell to a low, communal hum hardly distinguishable from that of the darting bees, dwindle away into a silence in which I hear a plane droning somewhere high up, frustratingly free.

I am back in the narrow wadi sneaking down to the sea. I shelter under a rock’s overhang, clutching the recently shunted-off-on-to-me Hotchkiss machine gun that I still do not fully understand. Peculiarly, I am alone but I know that in the wadis paralleling mine there is a bristling like cockroaches packing a crack in a wall of thousands of others who wait for the jesus of the ships that will never come. I have stared at the grain of the rock for so long that it has become a grain on the inside of my skull.

A bomber, pregnantly not ours, lumbers over the wadi on its way to the sea, its shadow huge on the ground, its belly seeming to skim rock, scrub, sand. I dutifully pump the gun’s last exotic rounds at it, marvelling that, for once, the gun does not jam. But there is no flowering of the plane into flame, no gratifying hurtling of it into the glittering enamel of the sea, and I stare after it as it rises into higher flight and am drained as one who has milked his seed into his hand.

Later, a shell explodes near the sea, the sand and the windless air deadening it into the slow-motion of a dream, and the sun sets into the usual heedless blood-hush of the sky.

I squat down beside the now useless gun, resting my back against its stand, thinking I will not sleep, staring into the heart of darkness that is a night that may not attain to any dawn. But I am wrong. There are muted thunderings, stuttering rushes of nearer sound, an occasional screaming of men or some persisting gull, but I strangely sleep, as strangely do not dream, and am woken – not by any uproar but a silence – to a sun still far from where I have slumped down into the foetal coil. I do not need any loudhailer to tell me that the lines are breached, that the sand is as ash under my feet.

Dully, I struggle up, still tripping over trailing sleep, slop petrol over the gun and the truck of anti-gas equipment deeper in under the rock, curse all the courses at Helwan that readied frightened men for the nightmare that never was. The synthetics of the suits, gloves, boots, intolerably flare.

Down at the dead end of the beach, I wash my face in the tideless sea, stare out over the still darkened warm-as-blood water to the skyline that has become a cage’s prohibitive ring, go back, then, to the higher, now sunlit land where silent men are smashing rifles over rocks with the ferocity of those who wrestle serpents with their bare hands.

I pass what is clearly an officer’s tent. It is dug in until only the ridge shows, neat steps leading down. Outside, a batman is washing a china plate, saucer, cup, his pug-dog peasant’s face seemingly unconcerned, but it does not raise from its staring down at the trembling of the hands.